Annual Report to Parliament for the 2016 to 2017 Fiscal Year: Benefits and Costs of Significant Federal Regulations, and the Implementation of the One-to-One Rule

We have archived this page and will not be updating it.

You can use it for research or reference. Consult our Cabinet Directive on Regulations: Policies, guidance and tools web page for the policy instruments and guidance in effect.

December 2017

This is the first annual report to Parliament on the benefits and costs of new federal regulations.

Parliament and Canadians expect Canada’s regulatory system to function well and to be responsive and transparent. This report is part of regular monitoring of certain aspects of the system to help ensure its overall health.

This report has two main sections:

- Section 1 describes the benefits and costs of regulatory proposals that were made by the Governor in Council (GIC) and that had significant impacts

- Section 2 reports on the implementation of the One-for-One Rule, in fulfillment of the Red Tape Reduction Act’s reporting requirement

The regulations reported on in this document were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, between April 1, 2016, and March 31, 2017.

Message from the President

As the President of the Treasury Board and the Minister responsible for federal regulatory policy and oversight of the regulatory system, I am pleased to present this report to Parliament. It is the first Annual Report to Parliament on the Benefits and Costs of Significant Federal Regulations, and the Implementation of the One-for-One Rule for the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year.

This report demonstrates the Government’s commitment to openness and transparency by engaging Parliament and Canadians on the management of federal regulations. It outlines, in an integrated and comprehensive manner, key information on the costs and benefits of significant regulations and on the implementation of the One-for-One Rule, an important element of the Government’s ongoing efforts to reduce needless administrative burden.

Canada benefits from a strong regulatory system, built on principles of protecting and advancing the public interest, developing regulations transparently and openly, making decisions based on evidence, and supporting a fair and competitive economy.

We should always be looking to make improvements. We will continue to find efficiencies and reduce unnecessary regulatory differences across jurisdictions to make the regulatory system less burdensome for businesses and consumers.

I invite you to read this report to see how the Government is designing effective regulations to protect our environment and the health, safety and security of Canadians.

Original signed by:

The Honourable Scott Brison

President of the Treasury Board

Types of federal regulations

Regulations are a type of law intended to change behaviours and achieve public policy objectives. They have legal binding effect, and are made by every order of government in Canada in accordance with responsibilities set out in the Constitution Act.

Regulations are used to support a broad range of objectives, such as:

- health and safety

- security

- culture and heritage

- a strong and equitable economy

- the environment

Federal regulations deal with areas of federal jurisdiction, such as patent rules, vehicle emissions standards and drug licensing.

There are three principal categories of federal regulations, based on where the authority to make regulations lies:

- Governor in Council (GIC) regulations are reviewed by a group of ministers who recommend approval to the Governor General. This role is performed by the Treasury Board.

- Ministerial regulations are made by a minister who is given the authority to do so by law.

- Example: The Health of Animals Act gives the Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food the authority to make regulations that permit compensation for costs related to the disposal of animals as part of disease control activities by the Government of Canada. Such authority includes setting maximum amounts of compensation or the manner for determining the maximum amounts.

- Other regulations made by an agency, tribunal or other entity that has been given the authority by Parliament to do so in a given area.

- Example: The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission can make regulations related to broadcasting and telecommunications.

The findings of this report are based on GIC regulations only, which represent approximately two thirds of all regulations approved per year.

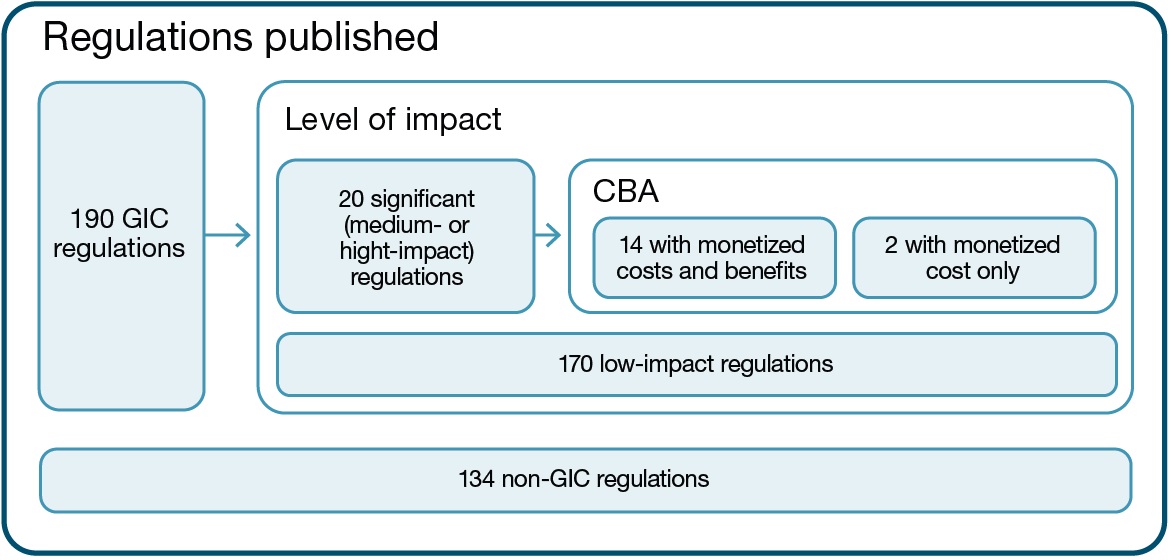

In the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, a total of 324 regulations were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, of which:

- 190 were GIC regulations (59% of all regulations)

- 134 were non-GIC regulations (41% of all regulations)

Section 1: benefits and costs of regulations

The process for making regulations in Canada

There are three main aspects to the process of making federal regulations in Canada:

- Regulatory development: Departments and agencies develop proposals for regulations based on the authorities established in legislation and on expectations set out in the Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat works with departments and agencies to:

- develop appropriate evidence, such as a cost-benefit analysis

- challenge the analysis in regulatory proposals for consistency with the Cabinet directive

- Central oversight: In general, proposed regulations are submitted by sponsoring ministers for consideration by the Governor in Council, which is defined in the Constitution Act as the “Governor General acting by and with the Advice of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada.” Since 2003, the Treasury Board has been designated as the Cabinet committee responsible for considering GIC matters, that is, the approval of regulations and most Orders in Council.

- Public transparency: Proposed GIC regulations are, with Treasury Board approval, published for public comment in the Canada Gazette, Part I (pre-publication).

- Pre-publication of regulatory proposals provides interested stakeholders and all Canadians with a description of the intent of proposed regulations and of the justification for them, with proposed regulatory text.

- Comments received following pre-publication can inform the final design of a regulation and the impact analysis for that regulation.

- Final regulations are, with GIC approval, published in Canada Gazette, Part II.

What is cost-benefit analysis (CBA)?

CBA is a decision-making methodology to determine the best approach to achieve a goal. CBA identifies and measures the positive and negative impacts of proposals so that decision-makers can determine the best course of action.

In the regulatory context, CBA is a structured approach to identify and consider the economic, environmental and social effects of a regulatory proposal. Since 1986, the Government of Canada has required that a CBA be done for most regulatory proposals in order to assess their potential impact on areas such as:

- the environment

- workers

- businesses

- consumers

- other sectors of society

Regulators must make a convincing case to decision-makers, stakeholders and Canadians that the regulatory approach recommended is superior to non-regulatory alternatives. Regulators must demonstrate that:

- the benefits to Canadians outweigh the costs

- the regulation has been structured so that the benefits outweigh costs as much as possible

The Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management requires that departments and agencies assess the benefits and costs of regulatory and non-regulatory measures, including scenarios where the government does not intervene.

The results of the CBA are summarized in a Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS), which is published with proposed regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I. The RIAS enables the public to:

- review the analysis

- provide comments to regulators before final consideration by the Governor in Council and subsequent publication of approved final regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part II.

Types of CBA

The scope and depth of analysis required for regulatory proposals depends on the cost component of each proposal. In general, the greater the estimated cost of the proposal, the more comprehensive the analysis of benefits and costs must be, and the greater the effort required to undertake this analysis.

For federal regulatory proposals, benefits and costs can be described in one of three ways:

- Qualitative: a cost or benefit that is only described and not measured physically

- Example: a qualitative benefit could be expressed as “this proposal will improve air quality”

- Quantitative: a cost or benefit that is expressed physically or as a quantity

- Example: a quantified benefit could be expressed as “this proposal is expected to reduce the incidences of respiratory illnesses in Canadian children by 90,000”

- Monetized: a cost or benefit for which the quantity is converted into a currency amount (for example, dollars) using an approach that considers both the value of an impact and when it occurs.[1]

- Example: a monetized benefit could be expressed as “this proposal is expected to save the Canadian health care system $10 million per year over the next 10 years through reduced hospital admissions”

Regulatory proposals are assessed through triage and are categorized according to their expected level of impact. The level of impact is determined primarily by the anticipated cost of the proposal.

Table 1: the 3 levels of impact

| Present value of costs (over 10 years) | Annual cost | |

|---|---|---|

| Low impact | Less than $10 million | Less than $1 million |

| Medium impact | $10 million to $100 million | $1 million to $10 million |

| High impact | More than $100 million | More than $10 million |

The level of impact indicated in the preliminary assessment of the proposal determines the type of CBA required. The degree of analysis and assessment required for a given regulatory proposal should be proportional to the anticipated level of the regulation’s impact. This proportionate approach is consistent with regulatory best practices set out by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Table 2: analysis required by level of impact

| Description of costs | Description of benefits | Annual cost |

|---|---|---|

| Low impact | Qualitative or quantitative | Qualitative |

| Medium impact | Quantified and monetized | Quantified and monetized

(if data are readily available) |

| High impact | Quantified and monetized | Quantified and monetized |

Regulatory proposals may include types of analysis beyond the requirements set out above. For example:

- a proposal that has a high or medium impact may include qualitative benefits and costs to support the monetized and quantified benefits and costs

- a low-impact proposal may include quantified or monetized analysis

This report covers only GIC regulations and is limited to those that are considered significant (those that have a medium impact or high impact).[2] Figures are taken from RIASs for regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year. To remove the effect of inflation, figures are expressed in 2012 dollars and vary from those published in the RIASs. This approach permits meaningful and consistent comparison, regardless of the year in which outcomes were originally measured.

Overview of benefits and costs of regulations

Of the 190 GIC regulations finalized in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year:

- 170 were low-impact (89% of GIC regulations and 52% of all regulations)

- 20 were significant (11% of GIC regulations and 6% of all regulations)

During this period, 134 non-Governor in Council regulations were published, and 190 Governor in Council regulations were published.

Of the 190 Governor in Council regulations, 170 were low-impact regulations, and 20 were medium- or high-impact regulations, also known as significant regulations.

Of the 20 significant regulations, 14 had cost-benefit analysis of monetized costs and benefits, and 2 had analysis of monetized costs only

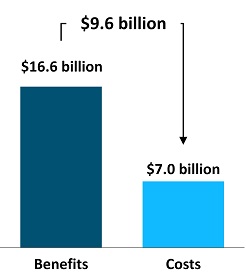

Monetized benefits and costs

An analysis of monetized benefits and costs is required for all significant regulatory proposals. As mentioned, medium-impact proposals are not required to monetize benefits when data is not readily available. Although some low-impact proposals include a full CBA, such proposals are the exception. The data on CBAs provided in this report are from medium- and high-impact proposals.

Of the 20 significant regulations, 16 had monetized impacts, representing 8.4% of GIC regulations and 4.9% of all regulations. Of these:

- 14 had monetized benefits and costs

- 2 had monetized costs only

During this period, 134 non-Governor in Council regulations were published, and 190 Governor in Council regulations were published.

Of the 190 Governor in Council regulations, 170 were low-impact regulations, and 20 were medium- or high-impact regulations, also known as significant regulations.

Of the 20 significant regulations, 14 had cost-benefit analysis of monetized costs and benefits, and 2 had analysis of monetized costs only

- ↑ The Secretariat recommends that present values be estimated using a 7% discount rate. This rate is based on a weighted average of foreign and domestic sources of capital funding for private sector projects. In some cases, benefits and costs may occur in areas that do not crowd out or create private investment. In such cases, a lower discount rate, the social discount rate, of 3% may be appropriate.

- ↑ Throughout this report, when describing a proposal or regulations, the term “significant” denotes a proposal or regulations that have a medium to high impact.