Important: The GCConnex decommission will not affect GCCollab or GCWiki. Thank you and happy collaborating!

The Idea Journey

| The custodians of this article would like to control editing at this time. Thank you. Please use the discussion page for suggestions and comments. |

An Approach to Inspiring Innovation in Government

by Timothy Philps

This article was originally published in: Financial Management Institute of Canada e-Journal 3, Spring 2019: 5-8. https://fmi.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/ENG-Spring2019_eJournal_issue3.pdf

La version Française: Circuit des idées

On a warm Roman spring morning in 30 AD, a young man named Appius walked down the Via Sacra toward the Foro Romano. He had a bounce in his step as he anticipated the many discussions that would ensue when he got to the Basilica Julia, the grand hall in the centre of the Forum. The Basilica was the place where Appius went to hear about issues, proposals, and news from faraway places. He was excited to share his ideas with other smart minds.

What Appius was a part of – almost 2,000 years ago – was not just a place where ideas could be exchanged and developed, but a broader culture of innovation that existed in Rome’s late republic and early imperial period. It produced some of the most staggering innovations in history. Well-known innovations, such as concrete or the arch, allowed for the building of now famous structures like the Pont du Gard aqueduct or the Roman Coliseum. The Romans created a culture where innovation was treasured. Leaders encouraged learning, valued knowledge, and rewarded accomplishments. They created a culture of prolific innovators.

Innovation in the Roman Empire, however, was not without challenges, and the barriers they faced were surprisingly like those faced by today’s large government organizations. The absence of competitive pressures that influence commercial organizations can produce a stand-pat mentality and resistance to change. Increasing public intolerance for missteps by government organizations has increased their aversion to risk. The hierarchical governance of the public sector has produced a top-down approach to innovation which overlooks the employees on the ground. Finally, increasing centralization of organizations has narrowed the catchment potential for ideas.

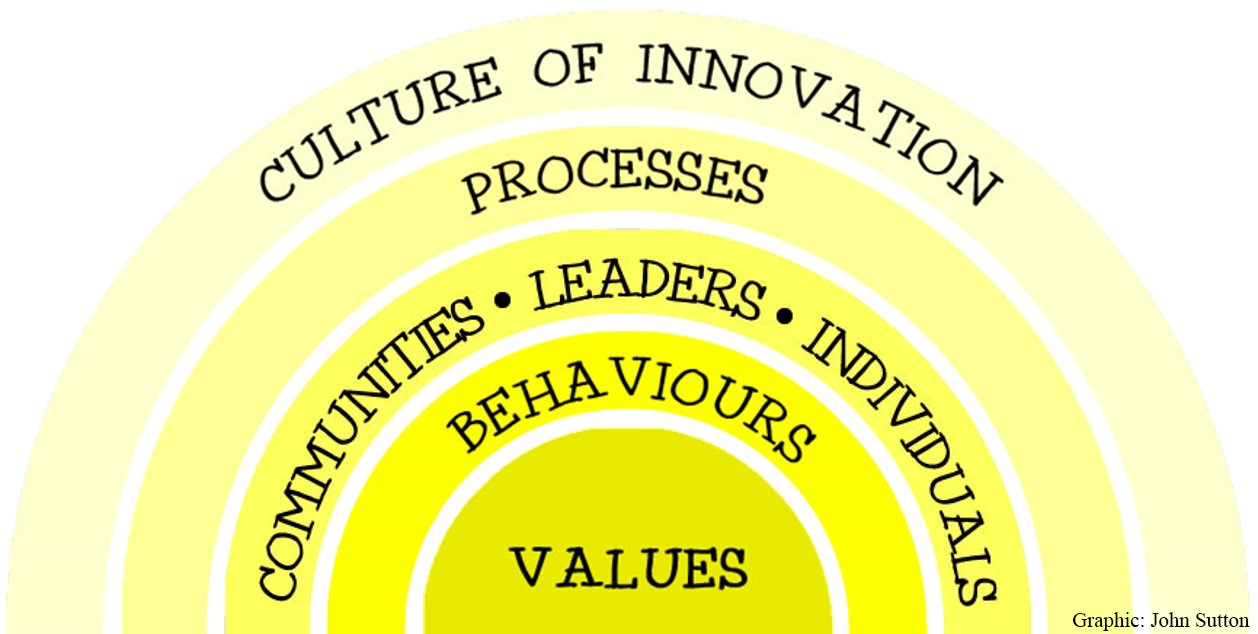

A Culture of Innovation

Creating an innovative culture in large government organizations, whose core business is not innovative, is difficult. The skill sets and expertise of employees is largely focused on the core deliverables of the organization, such as financial regulation, tax administration, economic development, health management, or education, just to name a few. Government organizations often look longingly at commercial companies that have clear innovative cultures such as those in high tech or emerging industries. That comparison, however, is not fitting. Commercial organizations often have a mandate to create something faster, smarter, and newer and their core values reflect that. It is different for government. What government organizations do have is an entrenched set of values; and that is where we will start.

The core values of most government organizations are some combination of integrity, respect, collaboration, cooperation, reliability and fairness. Managers and employees are made aware of these values from the time they join the organizations. They live them and practice them throughout their careers. That respect for core values creates a culture. The key to creating an innovative culture in government organizations therefore is to embed innovation as a core value and send a clear message that innovative behaviours are valued as much as behaviours associated with the other traditional core values.

There are several key innovative behaviours that the organization should value. An innovative culture requires collaboration with a focus on working together. Determination must be valued, along with an element of provocation. Egos need to be checked and organizations must be open and transparent about ideas and initiatives. Hits must be recognized, and misses supported. Who in the organization should demonstrate innovative behaviours and values? The short answer is everybody, but more easily identified as leaders, communities and individuals.

Leaders must provide inspiration, support and encouragement. Leaders must model innovative values and allow employees to take risks and ensure an environment where failures are not fatal. They must create a fearless environment. Leaders must also take a step back when successes are recognized and a step forward when an idea fails.

Organizations are comprised of dozens of communities such as work teams, management groups and special committees. These communities must challenge themselves to be creative and seek common solutions. They must support each other and use their collective influence to promote the innovative culture. Individuals should feel free to challenge what has been the norm. They must be passionate and relentless. They should be comfortable taking thoughtful risks.

When we refer to thoughtful risks, it is perhaps instructional to reflect on the Roman experience. A story is told that around 50 AD a glassmaker invented a type of glass that was extremely durable. He obtained an audience with Emperor Tiberius, where he demonstrated its incredible properties and boasted that he was the only person that knew how to make it. Fearing that the material would adversely affect the value of his vast stockpiles of silver and gold, the Emperor had the inventor beheaded. Understanding the current risks of any innovation is a clever tip.

A culture of innovation exists when leaders, individuals and communities embrace innovative values and behaviours. Yet, inspiring innovation in government goes beyond the requirement for an innovative culture. There must also be a process to capture ideas and development them to reality; I call that process the Idea Journey.

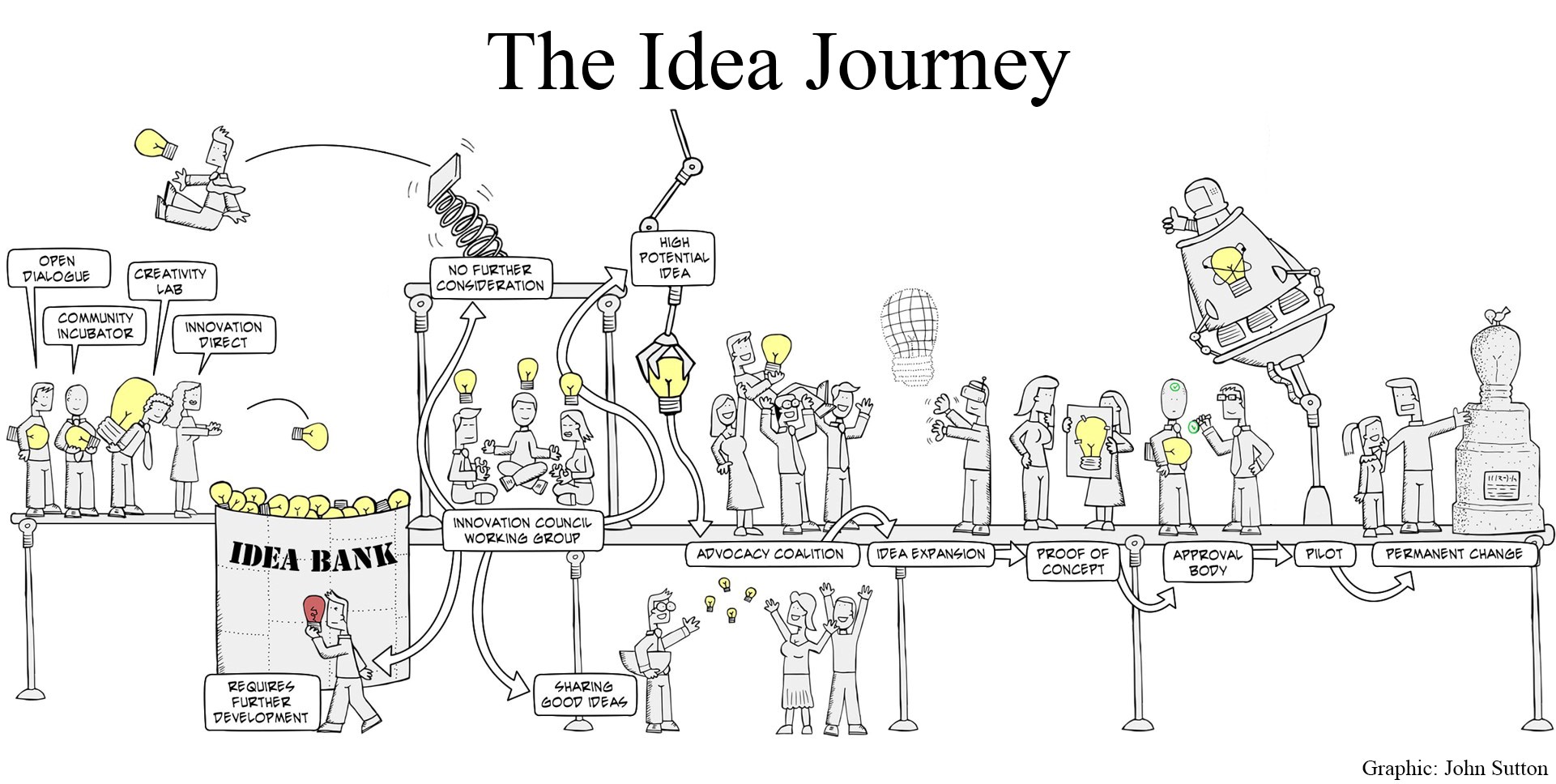

The Idea Journey

The Idea Journey receives its oversight from the Innovation Council which is comprised of employees and managers from throughout the organization. It is important that a variety of levels and disciplines from all offices are included to ensure a diversity of opinion and perspective.

Hierarchy does not matter in the Innovation Council; everyone is an equal contributor. A member’s involvement is in addition to their regular duties and amounts to about two days a month. They meet in-person a couple times a year with the balance of their interaction being virtual.

An innovation website is necessary to manage the Idea Journey. The website engages all employees in an interactive process to collaborate and express innovative ideas, store the ideas, provide transparency as the ideas move through the journey, and most importantly is a communication vehicle for promoting an innovative culture.

The purpose of the Idea Journey is to make it easy for every member of the organization to suggest any ideas they may have.

Opportunities for discussing, creating and submitting ideas are much more fulsome than the age-old suggestion box. The Idea Journey has four ways to capture ideas.

- Innovation Direct is the portal for anyone to submit their idea directly to the Innovation Council. It consists of an online form that identifies the submitter and requests a brief description. Innovation Direct gives a voice to employees who feel their ideas or suggestions may be obstructed by superiors who either kill their idea or simply claim it as their own. It is important that ideas are not submitted anonymously. Firstly, recognition is an important feature of an innovative process; employees should be acknowledged for their submissions. Secondly, the submitter is best positioned to assist in advancing their idea and working with the Council since they alone know what was envisioned.

- Open Dialogue is a crowd sourcing or virtual discussion utilizing social media. Conversations occur on a specific topic with the goal of fleshing out an idea that will eventually be submitted to the Innovation Council. Social media engages employees who are more comfortable on this platform to collaborate and express innovative ideas.

- The Community Incubator is a mobile, facilitated discussion forum that is inserted into existing management forums, team meetings and other gatherings with the specific intention of generating new ideas and submitting them to the Innovation Council. The many meetings that employees attend therefore become a source and opportunity for capturing ideas.

- The Creativity Lab is the Innovation Council itself and utilizes its understanding and expertise of innovation to generate original ideas. Brainstorming and discussion occur in a creative, unconstrained and diverse environment.

- All ideas that are submitted are captured in the Idea Bank. Managed by the Innovation Council, the Idea Bank is where ideas are organized and assigned to an Innovation Working Group. The Idea Bank is visible on the innovation website and open for comment by anyone wishing to share. Innovation Working Groups are smaller sub-groups of the Innovation Council and are assigned ideas to evaluate, consider, triage and shepherd through the Idea Journey.

The ideas are triaged by the working groups into four categories:

- No longer considered – these ideas have insurmountable barriers or have no usefulness.

- Need further development – these ideas have merit but require further development and are sent to the Creativity Lab.

- Worth sharing – these ideas have value but require no additional work and are therefore posted on the website as being best practices.

- High potential – these ideas should be advanced without delay and are worthy of investing resources in their development.

Ideas that have been determined to have high potential and which require additional effort are moved to the next step of the Idea Journey; the Advocacy Coalition. One of the most significant barriers for employees wishing to develop their ideas is often their lack of access to those in the organization that can make things happen. It is often difficult to break out of their hierarchical or organizational constraints and engage IT, HR, HQ, Finance or anyone necessary to develop an idea. The Council uses its influence to draw together the essential components to form the Advocacy Coalition which includes technical experts, project leaders, strategic partners and corporate support.

The idea has almost completed its journey and has now reached a point where it can be clearly articulated and receive the appropriate risk assessment. A proof of concept is prepared for presentation to the Innovation Council. The Innovation Council ensures that everything has been considered, risks have been addressed, and the idea is ready for submission to the Approval Body. It is this step that would have been helpful for our doomed Roman glass-maker.

As I offered at the outset, there are many differences between government organizations and commercial innovation-centred organizations. It cannot be forgotten that government organizations have an accountability to citizens to exercise impeccable stewardship and trust. Any innovation process must include – with whatever rigour is suitable for the idea or organization – an approval step by a management body. Depending on the implications or scope of the idea, this could be a local management team, regional management team, or whatever is appropriate. The purpose of the approval body is to authorize the idea becoming a pilot or prototype.

A Pilot or prototype is then used to evaluate and adjust the idea. At any time, the idea can loop back to any stage for further development. When the idea moves out of the pilot stage, it has ended its journey and has now become permanent.

The Idea Journey addresses the two critical components that I feel are necessary for inspiring innovation in government organizations: i) developing a culture of innovation through values, behaviours, individuals, leaders and communities and ii) providing a comprehensive process that engages the entire organization in capturing, developing and implementing ideas.

On that spring day in Rome, Appius was optimistic that his ideas would be accepted within a culture of innovation and be part of a process to make them a reality. Modern government organizations can provide the same inspiration to their innovators by adopting the Idea Journey.