Important: The GCConnex decommission will not affect GCCollab or GCWiki. Thank you and happy collaborating!

GC Service & Digital Target Enterprise Architecture

The GC EARB information is now maintained on GCX

GC Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture Whitepaper[edit | edit source]

Version: 1.33

November 4, 2020

Office of the Chief Information Officer of Canada, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Government of Canada

Executive summary[edit | edit source]

The Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture is an enabler for the Policy on Service and Digital.

The Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture defines a model for the digital enablement of GC services that address many of the critical challenges with the current GC enterprise ecosystem. It seeks to reduce the silos within the current GC ecosystem by having departments adopt a user‑ and service‑delivery‑centric perspective when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. It advocates a whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned with business services and where solutions are based on reusable components implementing business capabilities optimized to reduce unnecessary redundancy. This reuse is enabled using published application programming interfaces (APIs) shared across government. This approach allows the government to focus on improving its service delivery to Canadians while addressing its challenges with legacy systems.

The Policy on Service and Digital and the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture are guided by a commitment to the guiding principles and best practices of the Government of Canada Digital Standards:

- design with users

- iterate and improve frequently

- work in the open by default

- use open standards and solutions

- address security and privacy risks

- build in accessibility from the start

- empower staff to deliver better services

- be good data stewards

- design ethical services

- collaborate widely

Purpose of this paper[edit | edit source]

This paper is intended to assist federal institutions by providing recommendations on how systems could be implemented over the next several years to provide Canadian citizens with a more cohesive and sustainable digital landscape when interacting with the Government of Canada.

The intended audience is those involved in the delivery of digital services within the Government of Canada including deputy heads and chief information officers. The white paper will also inform suppliers of the enterprise architecture direction, assisting them to align their services when interacting with the government. Finally, the white paper will inform the Canadian public and the international community of the Government of Canada’s enterprise architecture direction for digital transition.

Unless otherwise specified, any example mentioned in this white paper does not represent any existing plans of the Government of Canada.

This white paper is not meant to replace existing documents that address the government’s strategic direction on digital services.

Digital government[edit | edit source]

A digital government puts people and their needs first. It is accountable to its citizens and shares information with them. It involves them when making policies and designing services. It values inclusion and accessibility. It designs services for the people who need them, not for the organizations that deliver them.

The Government of Canada is an open and service-oriented organization that operates and delivers programs and services to people and businesses in simple, modern and effective ways that are optimized for digital and available anytime, anywhere and from any device.

Digitally, the Government of Canada must operate as one to benefit each and every Canadian.[1]

Policy on Service and Digital[edit | edit source]

The Policy on Service and Digital and supporting instruments serve as an integrated set of rules that articulate how Government of Canada organizations manage service delivery, information and data, information technology, and cybersecurity in the digital era. Other requirements, including but not limited to, requirements for privacy, official languages and accessibility, also apply to the management of service delivery, information and data, information management and cybersecurity. Those policies, set out in Section 8, must be applied in conjunction with the Policy on Service and Digital. The Policy on Service and Digital focuses on the client, ensuring proactive consideration at the design stage of key requirements of these functions in the development of operations and services. It establishes an enterprise‑wide, integrated approach to governance, planning and management. Overall, the Policy on Service and Digital advances the delivery of services and the effectiveness of government operations through the strategic management of government information and data and leveraging of information technology.

Section 4.1.2.3 of the Policy on Service and Digital. The Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Canada is responsible for: Prescribing expectations with regard to enterprise architecture.

Section 4.1.2.4 of the Policy on Service and Digital. The Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Canada is responsible for: Establishing and chairing an enterprise architecture review board that is mandated to define current and target architecture standards for the Government of Canada and review departmental proposals for alignment.

Section 4.1.1.1 of the Directive on Service and Digital. The departmental Chief Information Officer (CIO) is responsible for: Chairing a departmental architecture review board that is mandated to review and approve the architecture of all departmental digital initiatives and ensure their alignment with enterprise architectures.

What problems does the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture address?[edit | edit source]

Canadians rely on the federal government for programs and services, which in turn depend on reliable, authoritative data and enabling information technology capabilities to ensure successful delivery. The GC enterprise ecosystem consists of all the information technology used by the Government of Canada and all related environmental factors. The interdependence of all elements with the ecosystem is an essential aspect of what makes it an ecosystem. When discussing information technology within the GC enterprise, one must consider the ecosystem.

What is the issue?[edit | edit source]

The Government of Canada has reached a critical point in its management of the IT systems that are used to enable the delivery of government services. There is an increasing gap between the expectations of Canadian citizens and the ability of the government’s legacy systems to meet those expectations. The total accumulated technical debt associated with legacy systems has reached a tipping point where a simple system‑by‑system replacement approach for individual systems has increasingly become cost and risk prohibitive. The business processes in place to manage the life cycles of these IT systems have become barriers rather than enablers.

How did we get here?[edit | edit source]

| Changing expectations | The rapid evolution of the internet as the ubiquitous platform for service delivery has outstripped the government’s ability to address the demand. Citizens have an increased expectation that all government services will be reliably delivered 24 hours a day, 7 days a week with no artificial differentiation based on which department provides the service. The introduction of new disruptive technologies outside of government can quickly shift the citizen’s expectations as they become aware of new approaches or capabilities. |

| Separate mandates | Government information systems have long mirrored the legislative separation of the functional mandates of departments. In part, this is because the original approaches to a delegation of authority and accountability in legislation did not contemplate the cross‑cutting dependency on information technology that exists today. Beyond authority and accountability, there are legislative constraints on intragovernmental information sharing has historically impeded the integration of business processes across government. Budget and funding models have further reinforced this separation. As a result, there have been limited opportunities to reduce overhead and eliminate redundancies across systems and across government. |

| Evolution of technology | Initially, business process automation within government was implemented as standalone solutions, in many cases monolithic and mainframe solutions. As time passed, the life cycle evolution of individual systems tended to limit their scope to those individual systems; reinforced by a desire to restrict procurement, technical, and change complexity and risk. Current technologies that could be used to implement cohesive enterprise approaches were introduced relatively recently, many years after most government systems were implemented. This gap has been exacerbated over time by the significant difference between the ability of the private sector and the public sector to adopt and leverage new technologies. |

Why is the problem so intractable? Why isn’t “business as usual” a workable way forward?[edit | edit source]

| “Business as usual” not effective | The “business‑as‑usual” approach would be to try to address each legacy system in isolation; in other words, a simplistic system‑by‑system replacement. The costs and risks associated with this approach for major legacy systems are prohibitive in most cases. Dealing with each system in isolation results in missed opportunities for reuse and for eliminating redundancies. In addition, these “big bang” methods dramatically increase business service delivery risk. By the time a significant replacement project is completed, there is also a substantial possibility that the underlying technology is out of date. To mitigate these issues, approaches that allow for an incremental and managed transition over time are suggested. |

| An alternative strategy | One alternative strategy is to incrementally migrate legacy systems by gradually replacing functional elements with new applications and services; in other words, an “evolve‑and‑transcend” strategy. This strategy implements an architectural pattern named the “Strangler Fig,” a metaphor for refactoring rather than replacing legacy systems, by incrementally replacing functional parts of a legacy application slowly and systematically over time, thus spreading costs and mitigating risks. |

Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture[edit | edit source]

The Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture defines a model for the digital enablement of Government of Canada services that address many of the critical challenges with the current GC enterprise ecosystem. It seeks to reduce the silos within the current GC ecosystem by having departments adopt a user‑ and service‑delivery‑centric perspective when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. It advocates a whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned to business services and solutions are based on reusable components implementing business capabilities optimized to reduce unnecessary redundancy. This reuse is enabled using published APIs shared across government. This approach allows the government to focus on improving its service delivery to Canadians while addressing the challenges with legacy systems.

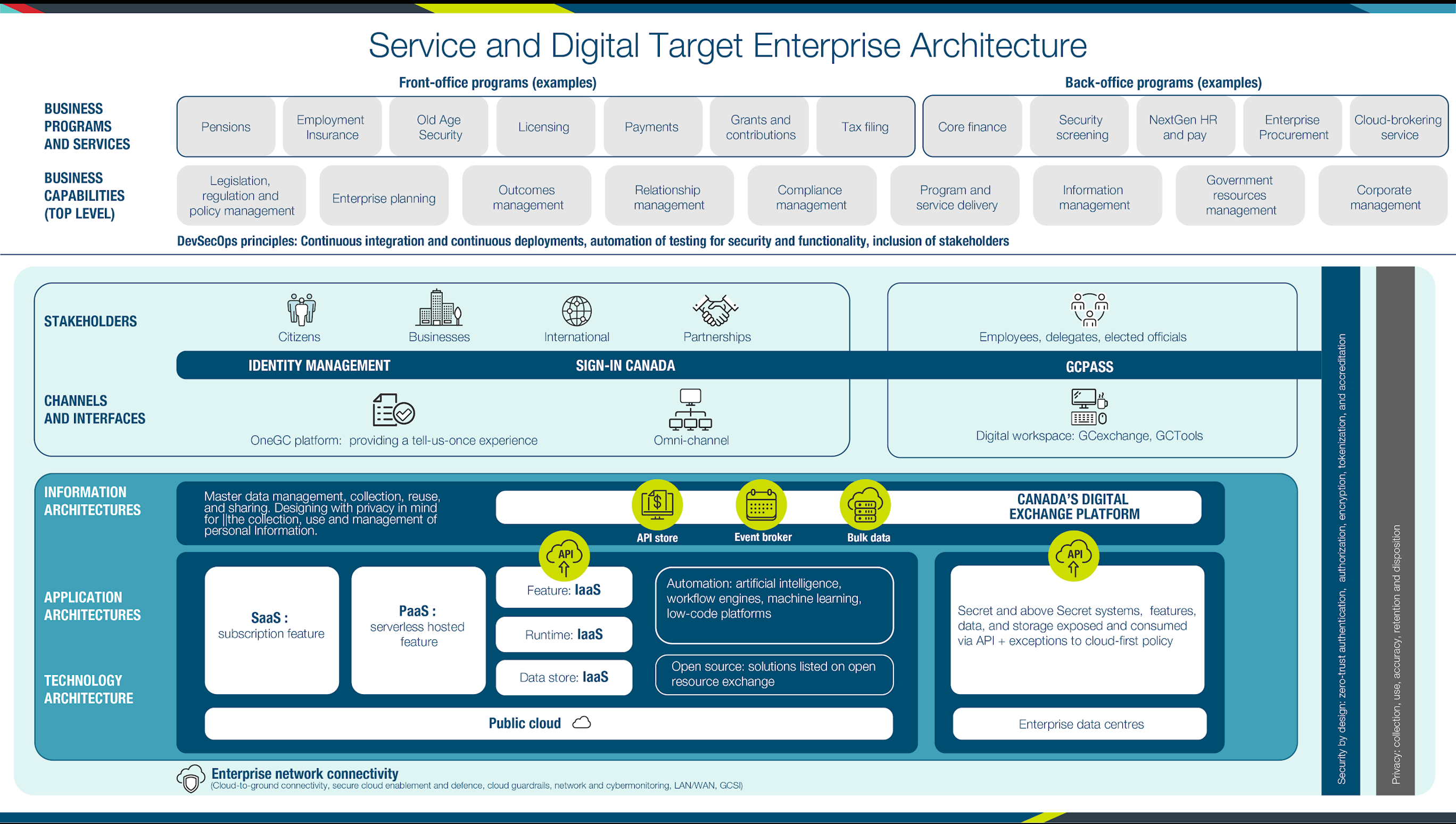

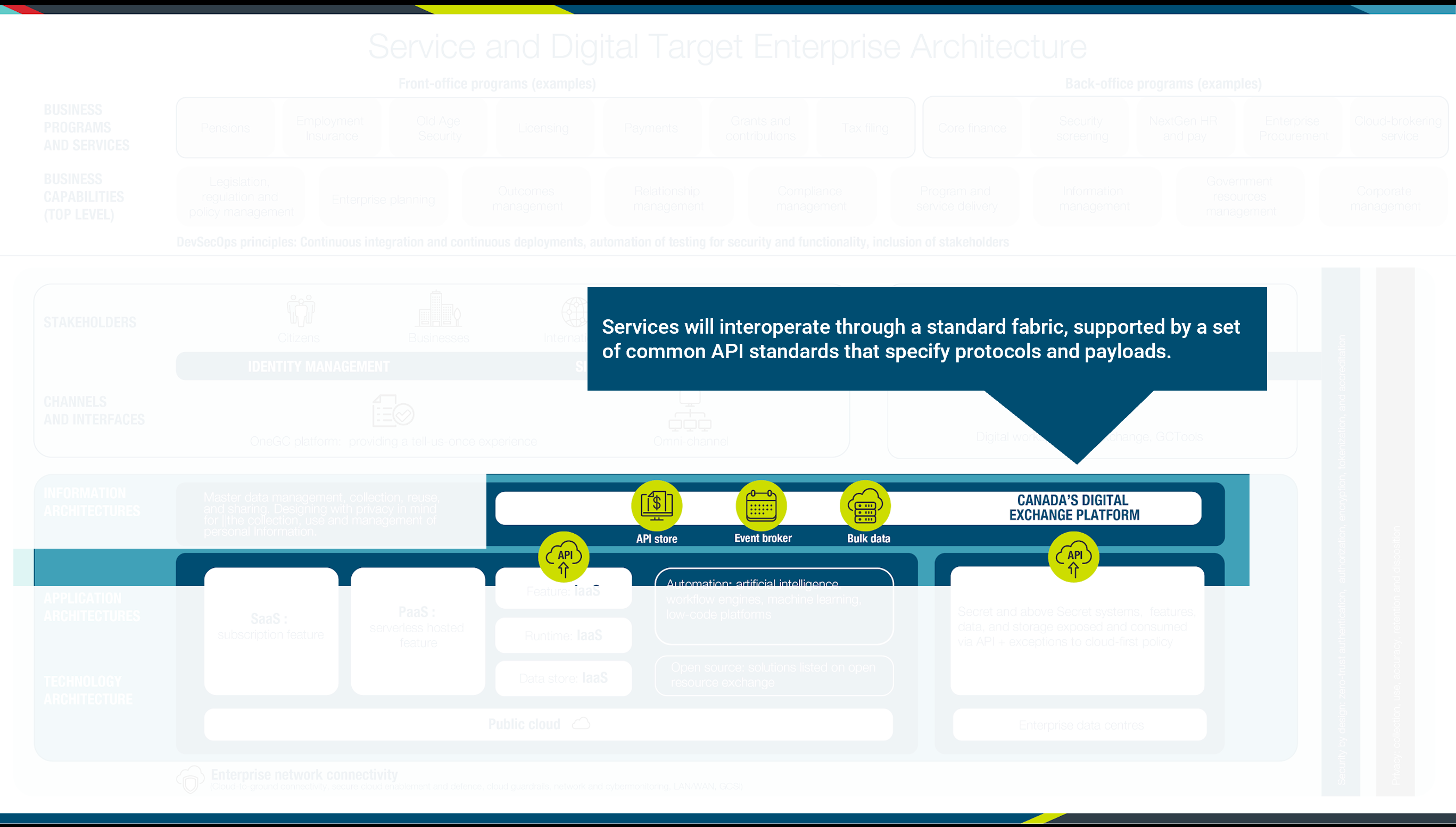

Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture - Text version |

|

The top row of the diagram shows examples of business programs and services, divided into two categories: front-office and back-office. Examples of front-office business programs and services:

Examples of back-office programs and services:

The second row of the architecture shows the top‑level business capabilities:

The third row lists the DevSecOps principles: Continuous integration and continuous deployments, automation of testing for security and functionality, inclusion of stakeholders The fourth row identifies the various stakeholders: Externally, examples include:

Internally, examples include:

Two examples of user authentication are presented under the external stakeholder:

A third example related to the internal stakeholders is GCPass. The fifth row identifies channels and interfaces. Externally accessible solution examples are:

The third example is related to internal users:

The next part of the graphic show the elements of the information architecture, application architecture and technology architecture. Information architecture

Canada’s Digital Exchange Platform offers the following capabilities:

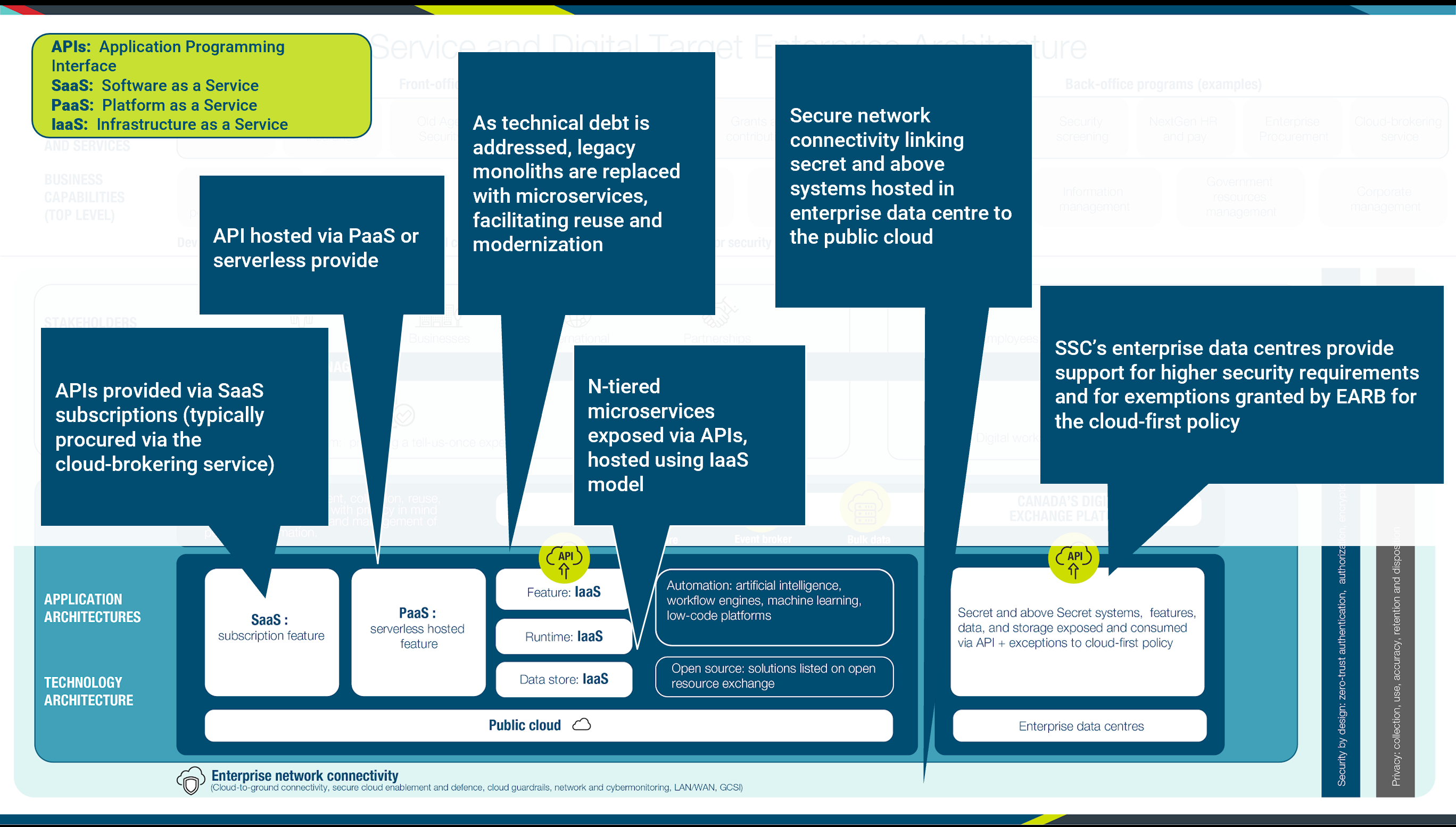

Application architecture is divided into two categories based on security requirements:

The information from these application architecture options is shared back to the Canada’s Digital Exchange Platform via APIs (application programming interfaces). Secret and above Secret systems, features, data, and storage exposed and consumed via API plus exceptions to cloud-first policy. Technology architecture Public cloud is the recommended architecture for solutions that are considered Protected B or below from an identified security level. Solutions above Protected B must use Enterprise Data Centres. All the layers of the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture rely on enterprise network connectivity. Examples of enterprise network connectivity include:

Along the right side of the graphic are two overarching principles:

|

The goal of the Service and Digital Target State Enterprise Architecture is to depict the Government of Canada’s future state in one picture. The diagram is divided into several parts, which are based on The Open Architecture Framework (TOGAF) framework explained in a subsequent section. This framework views business, information and data, applications, technology and security each as separate layers, having their own concerns and architecture.

The top layer of the diagram represents business architecture. The programs in this layer are categorized as front office, which provides services directly to citizens, academic institutions, and Canadian businesses, and back‑office services which support the government itself. Examples of front office programs include Employment Insurance and tax filing services, and examples of back‑end programs include finance security screening, pay, enterprise procurement, and business continuity.

In the following layer, key aspects of the top level of the GC Business Capability Model are depicted. This takes into consideration the IT plan investment framework and provides a mechanism to identify potentially redundant investments across, opportunities for rationalization, and identification of opportunities for enterprise solutions.

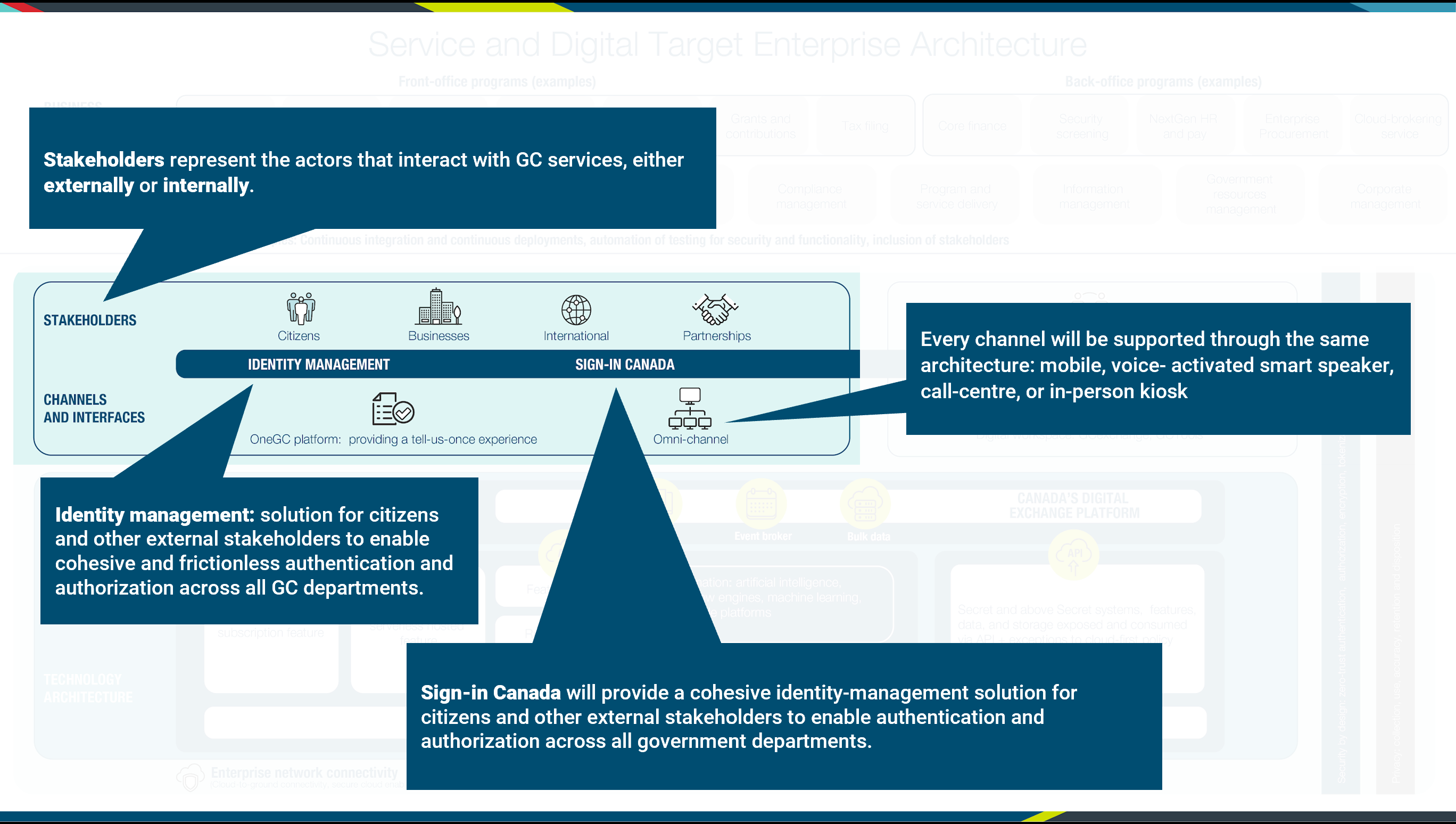

In the following layer, stakeholders represent the actors that interact with GC services, either externally (such as citizens, businesses, those which the GC is in partnership with such as universities or international actors), or internally, such as GC employees, delegates, or elected officials. They have different access (use of mobile, voice‑activated smart speakers, contact centres, and kiosks) and accessibility requirements, and may communicate in either official language. Sign‑in Canada will provide a cohesive identity management solution for citizens and other external stakeholders to enable authentication and authorization across all GC departments.

The goal is to respond to external users, who as clients, want interactions across governments to be managed with consistency, integrity, and trust so that they have a beneficial, personalized, and seamless experience.

To ensure consistency, every channel will be supported through the same architecture. Examples of these channels include mobile, voice‑activated smart speaker, call centre, or in‑person kiosk. This concept is called omni‑channel.

The next layer projects the idea of a service‑oriented government, with a user‑centred approach to the business of government that puts citizens and their needs as the primary focus of our work, using “tell‑us‑once” service approaches, integrated services across the GC program and service landscape in a way that provides real‑time information to Canadians about their service applications. It is a perspective centred on users and service delivery when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. It builds on business architecture guidance to design for users first, focusing on the needs of users, using agile, iterative, and user‑centred methods in a whole-of-government context.

Leveraging the concept of harmonization described for external users through Sign‑in Canada, GCPass will enable authentication and authorization to GC Systems for Internal stakeholders. The digital workplace will uniformly enable the work of public servants, building on a standard design.

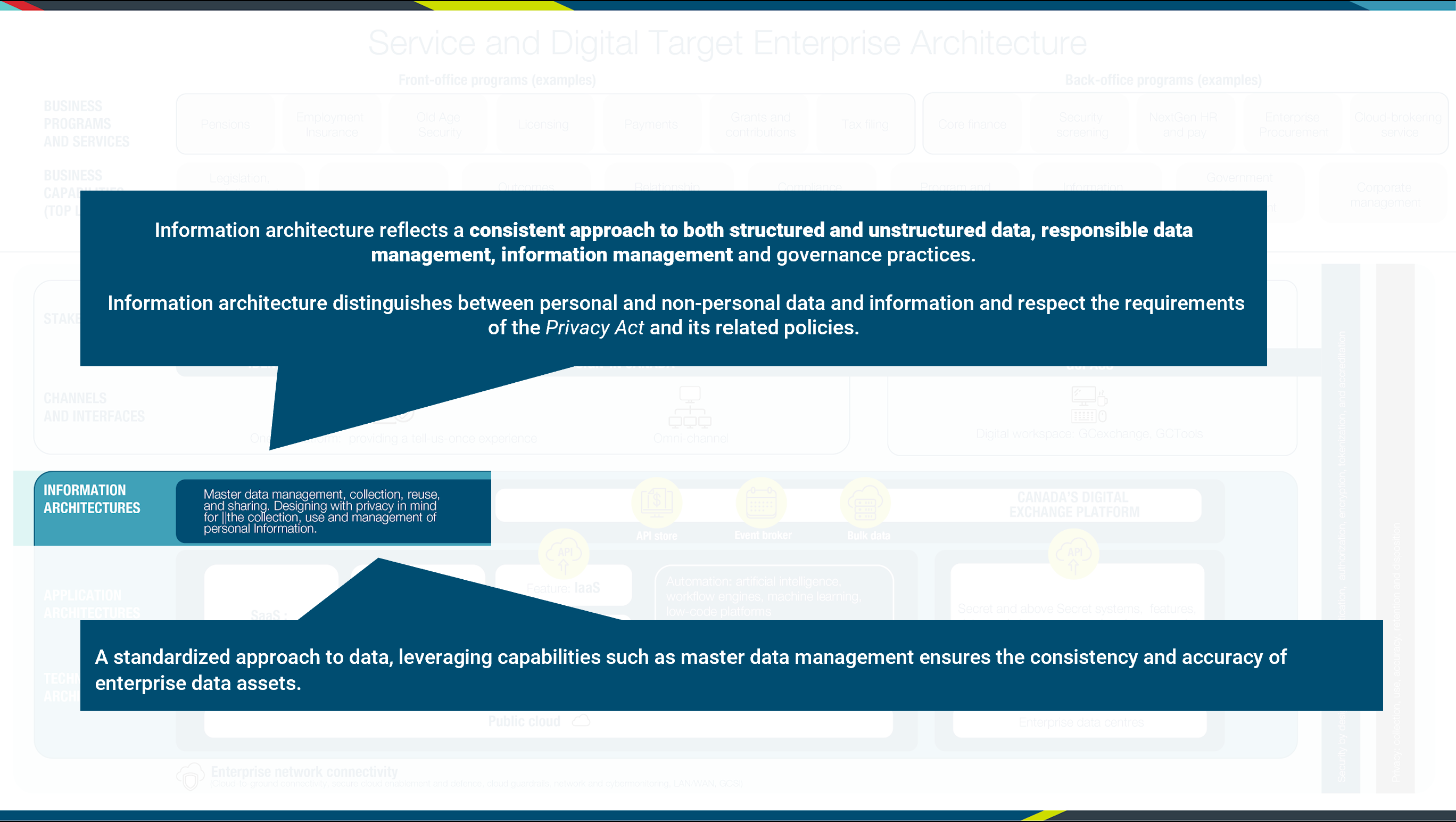

Information architecture is depicted in the following layer. Information architecture best practices and principles aim to support the needs of a business service and business capability orientation. To facilitate effective sharing of data and information across government, information architectures should be designed to reflect a consistent approach to data, such as the adoption of federal and international standards. Information architecture should also reflect responsible data management, information management and governance practices, including the source, quality, interoperability, and associated legal and policy obligations related to the data assets.

Information architectures should also distinguish between personal and non‑personal data and information as the collection, use, sharing (disclosure), and management of personal information must respect the requirements of the Privacy Act and its related policies.

The following layer depicts how services will interoperate through a standard fabric, supported by a set of common API standards specifying protocols and payloads. These services will be published in the API Store to facilitate reuse. APIs will be brokered through an API gateway to manage traffic, ensure version control, and monitor how services are exposed and consumed, either directly, or through a common event broker. Procurement of software as a service (SaaS) offerings will be facilitated through Shared Services Canada’s (SSC’s) Cloud Brokering Service and supported through their managed services. These are services that are available to steward infrastructure that are offered by SSC include database management services, cabling, facility management, transition planning and support, system integration services, and project management, among others. GC business programs and services and their enabling capabilities are built on resources within the application and information landscapes.

Also highlighted in this layer are automation capabilities such as artificial intelligence and open source solutions listed on an open resource exchange.

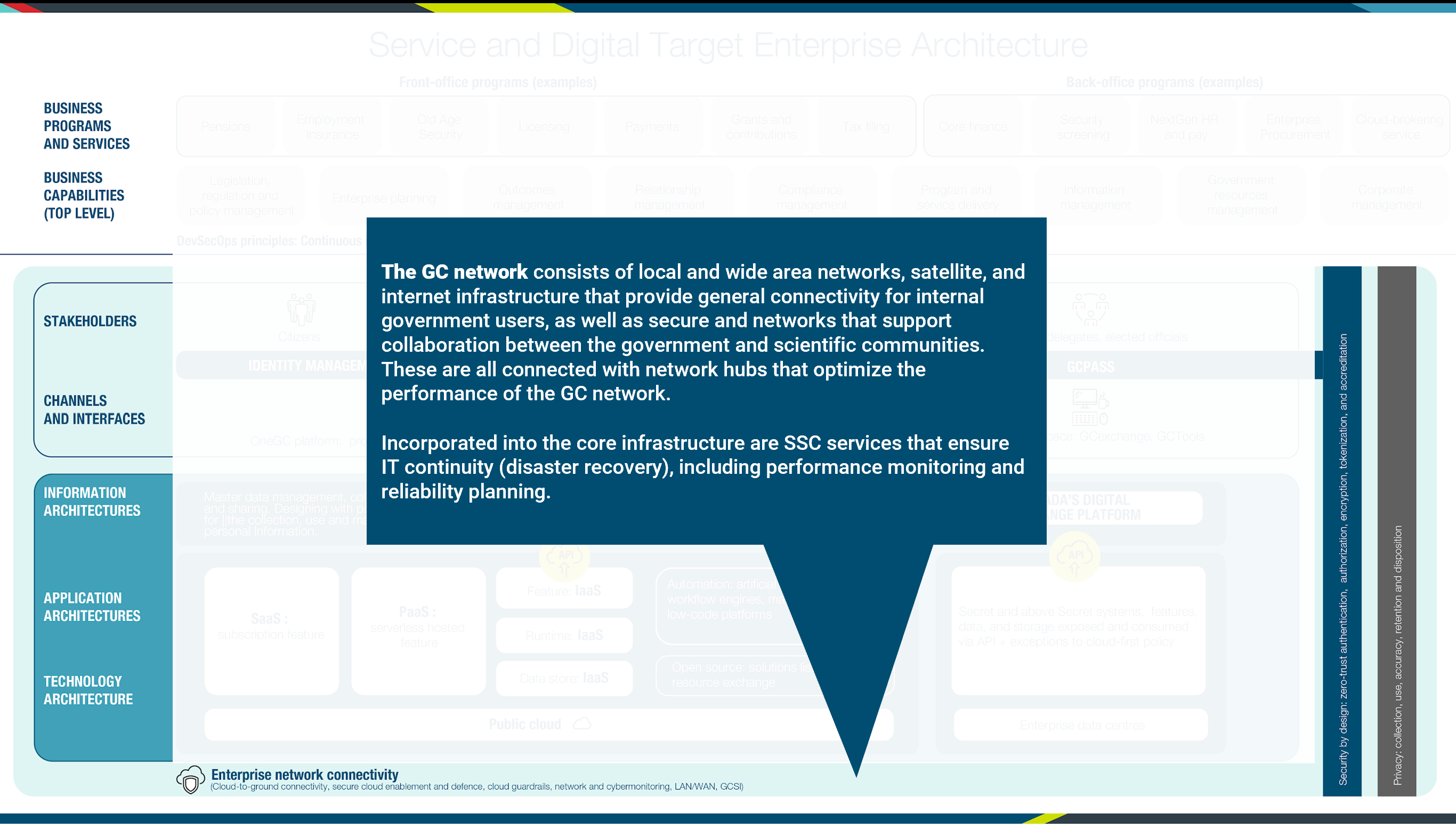

In the bottom‑most view of the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture, the focus is on the technology infrastructure that acts as the glue to bring everything together: the network. The GC network consists of local area network (LAN), wide area network (WAN), satellite, and internet infrastructure that provides general connectivity for internal government users, as well as secure and networks that support collaboration between the government and scientific communities. These are all connected with network hubs that optimize the performance of the GC network. The core infrastructure includes SSC services that ensure IT continuity (disaster recovery), including performance monitoring and reliability planning.

Security is reflected in the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture diagram as a cross‑cutting factor that spans all horizontal layers. The goal is to ensure security at all architectural levels, from design to implementation to operations; and to ensure authentication, authorization, auditing, monitoring, tokenization, and encryption of all data, whether at rest or in motion.

Improved outcomes[edit | edit source]

| Improved digital services that meet citizens’ expectations | Canadian citizens expect reliable digital services that deliver a cohesive user experience.

Their expectation for cohesive user experience is founded on their perception that digital services are being delivered by “one” government and not a collection of departments. By aligning digital service delivery to a common set of services defined within a GC Service Inventory and implemented using reusable components based on a common taxonomy of business capabilities, GC can improve the user experience. Their expectations for reliability and availability are based on their experiences with modern private‑sector internet services. By transitioning to public cloud offerings and infrastructure, GC can leverage private sector investments to meet citizens’ expectations for reliability and availability. |

| Managed costs and improved agility | GC needs to achieve economies of scale realized by modernizing and standardizing IT and by reducing its reliance on costly and outdated technology.

By encouraging the sharing of reusable components based on business capabilities and by leveraging private sector cloud solutions and open source software, GC can both reduce redundancy and help manage costs. By transitioning to an architecture that leverages public cloud offerings and infrastructure, GC can become more agile in responding to changes in business needs, thus delivering future‑ready IT systems that can support the GC digital transformation journey. |

| Engaged and effective workforce | Retention has been identified as a significant IT workforce and talent management issue. The ability to attract and retain new talent is challenging due to the perception that government IT is decades out‑of‑date. Besides the drain on workforce capacity, attrition has negatively impacted morale, the level of engagement and overall workforce effectiveness.

By adopting modern technology and practices, the government is in a better position to attract and retain new talent. Reducing attrition and boosting recent talent acquisition will have a positive impact on morale and foster an engaged and effective workforce. |

Realization practices and principles[edit | edit source]

To realize the GC Enterprise Ecosystem Target Architecture, departments should align with the practices and principles as outlined below, when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. The architectural approach was developed to facilitate managed incremental transitions but requires more strategic planning on the part of departments to be implemented effectively.

The Government of Canada Enterprise Architecture Framework defined below presents the evaluation criteria being used by GC Enterprise Architecture Review Board to align solutions to the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture. In the interest of effective communication to the architecture community of practice, the material has been organized based on the architectural domains business, information, application, technology, and security.

Enterprise architecture framework[edit | edit source]

The enterprise architecture framework is the criteria used by the Government of Canada enterprise architecture review board and departmental architecture review boards when reviewing digital initiatives to ensure their alignment with enterprise architectures across business, information, application, technology and security domains to support strategic outcomes.

Business architecture[edit | edit source]

Business architecture is a critical aspect for the successful implementation of the GC Enterprise Ecosystem Target Architecture. The architectural strategy advocates whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned to business services and solutions are based on re‑useable components implementing business capabilities in order to deliver a cohesive user experience. As such, it is essential that business services, stakeholder needs, opportunities to improve cohesion and opportunities for reuse across government be clearly understood. In the past these elements have not been a priority. It is expected that the IT culture and practices will have to change to make business architecture, in general, and these elements a primary focus.

| Design services digitally from end‑to‑end to meet the Government of Canada users and other stakeholders’ needs |

|

| Architect to be outcome‑driven and strategically aligned to the department and to the Government of Canada |

|

| Promote horizontal enablement of the enterprise |

|

Information architecture[edit | edit source]

Information architecture includes both structured and unstructured data. The best practices and principles aim to support the needs of a business service and business capability orientation. To facilitate effective sharing of data and information across government, information architectures should be designed to reflect a consistent approach to data, such as the adoption of federal and international standards. Information architecture should also reflect responsible data management, information management and governance practices, including the source, quality, interoperability, and associated legal and policy obligations related to the data assets. Information architectures should also distinguish between personal and non‑personal data and information as the collection, use, sharing (disclosure), and management of personal information must respect the requirements of the Privacy Act and its related policies.

| Collect data to address the needs of the users and other stakeholders |

|

| Manage and reuse data strategically and responsibly |

|

| Use and share data openly in an ethical and secure manner |

|

| Design with privacy in mind for the collection, use and management of personal Information |

|

Application architecture[edit | edit source]

Application architecture practices must evolve significantly for the successful implementation of the GC Enterprise Ecosystem Target Architecture. Transitioning from legacy systems based on monolithic architectures to architectures that oriented around business services and based on re‑useable components implementing business capabilities, is a major shift. Interoperability becomes a key element, and the number of stakeholders that must be considered increases.

| Use open source solutions

hosted in public cloud |

|

| Use software as a service (SaaS)

hosted in public cloud |

|

| Design for Interoperability |

|

Technology architecture[edit | edit source]

Technology architecture is an important enabler of highly available and adaptable solutions that must be aligned with the chosen application architecture. Cloud adoption provides many potential advantages by mitigating the logistical constraints that often negatively impacted legacy solutions hosted “on premises.” However, the application architecture must be able to enable these advantages.

| Use cloud first |

|

| Design for performance, availability and scalability |

|

| Follow DevSecOps principles |

|

Security architecture[edit | edit source]

The GC Enterprise Security Architecture program is a government‑wide initiative to provide a standardized approach to developing IT security architecture, ensuring that basic security blocks are implemented across the enterprise as the infrastructure is being renewed.

| Build security into the system life cycle across all architectural layers |

|

| Ensure secure access to systems and services |

|

| Maintain secure operations |

|

GC enterprise ecosystem transition[edit | edit source]

The realization of the Target Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture involves dozens of departments and thousands of applications and will involve many interim states. The technical strategy is to incrementally migrate legacy systems by gradually replacing functional elements with new applications and services thus spreading costs and mitigating risks. However, the fundamental nature of the change required demands more than just a technical strategy. To meet Canadians’ expectations for coherent digital service delivery, the government must modernize its policy and practices to support the technological transition to the target enterprise architecture.

Significant progress has already been made, particularly around enabling policy, and work has begun on changing practices, but much work remains.

Enabling policy and regulation[edit | edit source]

To support the change needed, the enabling policy and regulation must be aligned with the strategic direction. The policy must support the required changes and not be a barrier to adoption.

| Integrated policy and directive to enable change | Treasury Board approved a new Policy on Service and Digital and Directive on Service and Digital, which serve as an integrated set of rules that articulate how Government of Canada organizations manage service delivery, information and data, information technology and cybersecurity in the digital era. TBS, through the Office of the Chief Information Officer, developed guidance informed by departmental feedback, reviewed existing Treasury Board policy instruments and identified emerging areas.

TBS, through the Office of the Chief Information Officer, and departments will continue to update guidance and evolve Treasury Board policy instruments. |

GC enterprise focused practices[edit | edit source]

The proposed strategies and architectural principles are significant departures from past practices. Existing departmental practices for the management of IT have locked the government into a cycle that reinforces siloed approaches. The emphasis must shift from isolation and control to collaboration and sharing with the focus on cohesive service delivery to citizens rather than individual mandates.

| GC Target Enterprise Architecture | The Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture provides a framework and focal point for making informed decisions on the alignment of business solutions to GC needs. |

| GC Enterprise Architecture Framework | Business, information, application, technology, security, and privacy architecture domains defined by the GC to align solutions to the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture. |

| GC Enterprise Architecture Review Board (GC EARB) | The GC Enterprise Architecture Review Board (GC EARB) provides a governance mechanism to assess if proposed solutions are aligned to the GC Enterprise Architecture Framework. |

| Establishment of GC Enterprise Portfolio Management (GC EPM) | GC Enterprise Portfolio Management (GC EPM) will support integrated planning, prioritization, and optimization of an achievable enterprise investment portfolio by enabling the integration of critical processes and data to inform decision‑making, visibility, and transparency.

|

| Including the business capability perspective in the IT plan | The inclusion of Business Capability Model mapping in the IT plan investment framework provides another mechanism to identify potentially redundant investments in business capabilities across government and opportunities for rationalization and to identify opportunities for enterprise solutions. |

| Including the application capability perspective in the Application Portfolio Management framework | The inclusion of Application Capability Model mapping into the GC Application Portfolio Management framework provides another mechanism to identify overlapping application capabilities and unused functions. Reducing the technology footprint will decrease operational expenses and free up funds for other priorities. |

| GC Cloud Brokering | The GC Cloud Brokering provides a way for departments to obtain public cloud services already vetted. It simplifies the procurement and fulfillment of cloud services by providing a unified process for requesting cloud services that have been thoroughly investigated and approved to comply with the requirements of the GC, as well as to offer central agencies with the visibility of all environments in the cloud. |

| API store | The API store provides a mechanism to publish reusable business capabilities and access to data. |

| Open source software | The Open Source Policy and White Paper guided the use of software, the need for contribution to open source software, the publishing of open source software, and the acquisition of open source software. |

| Digital workspace standards and profiles | GC EARB created standards for internal enterprise services, defined digital workspace user profiles, set departmental consumption of IT services, and sets consumption metrics and limits for each of SSC’s 31 services. |

| Framework for Government‑Wide Data Governance and Stewardship | GC EARB introduced a government‑wide framework for data governance and stewardship, for TBS work on the development of principles, policies and guidance concerning “prescribing enterprise‑wide data standards.” |

GC enterprise IT ecosystem[edit | edit source]

The government has made some limited progress in common application capabilities such as document management and others. However, the predominantly monolithic architectures of departmental applications have effectively limited sharing and reuse across government. The transition towards the GC Target Enterprise Architecture is needed to achieve progress in that area.

| GC enterprise solutions | The establishment of GC enterprise solutions has provided a standard implementation for common application capabilities such as document management (GCDOCS), collaboration (GCshare), and Customer Relationship Management CRM (GCcase). |

| GC enterprise digital workplace platform | The acquisition of Office 365 provides a secure cloud‑based, software‑as‑a‑service solution for the digital workspace. Its rollout will provide a coherent user experience across government over multiple devices and channels. |

| Sign‑in Canada | Sign‑in Canada is a proposal for a unified authentication mechanism for all government digital engagement with citizens. Users would only need to tell Sign‑in Canada one time who they are, and subsequently, there would be no need to sign up multiple times to access different government services. |

| GC internal authentication | Internally within the government, GCPass, when fully implemented, will provide streamlined secure and appropriate access to GC systems for public servants. |

| Canadian Geospatial Platform | Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is launching the Canadian Geospatial Platform (CGP) as the next evolution of the Federal Geospatial Platform, with the transition to a new architecture for a GC enterprise platform that will enable NRCan to host solutions from other GC departments in a platform‑as‑a‑service model. CGP will continue to be aligned with the principles of open government and open data and thus is currently configured for unclassified data only. |

Summary[edit | edit source]

The Government of Canada is responding to the challenge of meeting Canadian citizens’ evolving expectations for cohesive digital service delivery in the face of aging IT systems and rising technical debt. To meet this challenge, the government is changing the way it approaches acquiring new solutions and modernizing older solutions. By advocating a whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned to business services, and solutions are based on reusable components implementing business capabilities optimized to reduce unnecessary redundancy, it is maintaining a clear focus on improving its service delivery to Canadians while addressing the technical challenges with its legacy systems.

The future digital landscape of the Government of Canada will be more agile in responding to changes in business needs and better able to leverage new disruptive technologies. Significant progress has already been made, particularly in enabling policy, and work has begun on changing practices, but much work remains.

An ongoing commitment is needed from everyone involved in digital service delivery to be engaged and active participants in these changes by adopting:

- a service‑centric perspective; and focusing on delivering a cohesive user experience for our citizens

- a business capability‑centric perspective when considering solutions, and embracing sharing and reuse

- a whole‑of‑government perspective; and embracing change

This white paper is just another small step of the larger journey.

- ↑ Digital Operations Strategic Plan: 2021–2024 - Canada.ca