PHAC Conflict of Interest Toolkit for Guideline Development

Background

Clinical and public health guidelines are “systematically developed, evidence-based statements which assist providers, recipients and other stakeholders to make informed decisions about appropriate health interventions.”[1]

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) develops a variety of guidelines that provide advice to policy-makers, public healthcare systems, and Canadians through the support of standing guideline panels, and by providing funding or collaborating with external organizations on ad hoc topics. Topic areas for PHAC guidance include travel medicine, immunizations, influenza prevention, problematic substance use, family violence, dementia, suicide prevention, traumatic head injury/concussions, physical activity, cancer prevention, sexual health, healthcare-acquired infections, and tobacco cessation.

To maximize their impact, guidelines should be free of conflicts of interest (COI) – situations in which the judgment of an individual involved in developing a guideline is unduly influenced (or seen to be unduly influenced) by a secondary interest (such as the opportunity to derive personal benefit).[1]

Given several high-profile news stories within and outside Canada,[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] the health community that benefits from evidence-based guidance and policy, and Canadians more generally, are increasingly aware of the importance of disclosing and managing COI in guidelines. These examples demonstrate the considerable reputational and other risks that poorly managed COI in the context of guidelines could pose to PHAC and its partners. Beyond that, proper management of COI is an established criterion for assessing guideline quality.[9]

PHAC has taken steps towards addressing the issue of COI in guideline development by hosting a Best Brains Exchange on the topic[10] in collaboration with CIHR. This meeting, which took place in January 2019, brought together over 60 participants representing academia, guideline producing groups from Canada and internationally, journal editors, and federal and provincial governments.

The principles put forward by the Guidelines International Network (GIN) are a key guiding document for improving the management of COI within guideline development, and were discussed extensively at the BBE.[10][11] The GIN principles provide a framework for consistent and appropriate management of COI in guideline development.[11] While there was broad agreement that implementation of these principles would improve COI management in Canadian guidelines, it was felt by many that support would be needed to fully implement these principles across various groups.

Overall, one clear theme emerged from the BBE: The need for national leadership, national standards, national approaches, and national transparency to help bring Canada up to the level of COI management seen in other countries.[10]

Shortly after the BBE, the Canadian Medical Association Journal, one of the foremost publishers of guidelines in Canada, announced that as of 2020, all groups publishing guidelines in their journal must adhere to the GIN principles.[12] Therefore it is anticipated that a key area for national leadership in this area will be to help Canadian guideline producers (within PHAC or external) in adhering to the GIN principles, and generally implementing best practices related to COI. For some groups, this may require only small shifts in their current policies and procedures, while for other groups (e.g., smaller or with less resources) this could require considerable work.

PHAC, through its Guidance Innovation Hub has developed a compendium of tools, listed on this page, that can be used by national guideline development groups to help improve their practices related to the management of COI, including adherence to the GIN principles.

PHAC COI disclosure form for guideline development

Coming soon.

PHAC COI assessment tool for guideline development

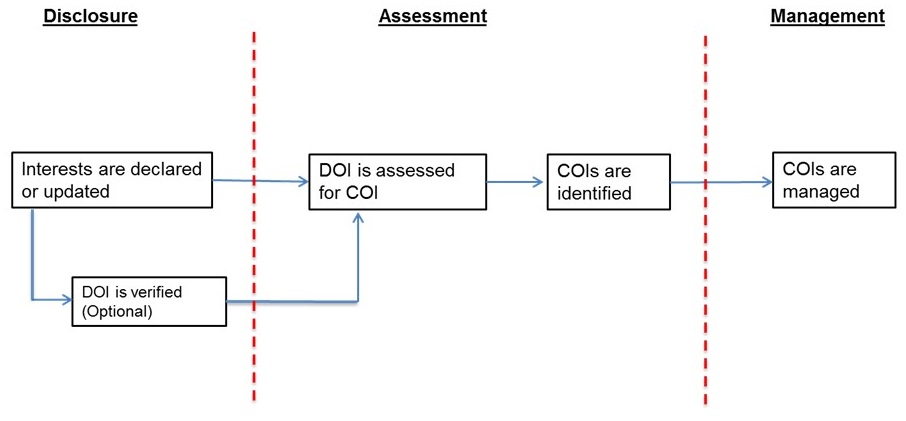

There is an important distinction to make between disclosed interests, and the presence of COI. Expert advisory panelists providing advice to PHAC or otherwise developing guidance (e.g., clinical practice guidelines) may have a wide variety of affiliations and interests. As noted by the World Health Organization, "The declaration of one or more secondary interests (declaration of interests) does not automatically mean that a conflict of interest is present: there is a distinction between the two. A transparent and objective process for assessing a declaration of interests is required to determine if a conflict exists and what its effects might be, and to manage any significant conflict of interest."[13] Figure 1 provides an overview of the link between disclosures of interests, and the identification and management of COI.

Individuals involved with guidance development panels (within PHAC, Health Canada, or otherwise) are regularly collecting disclosures of interests from their panel members. Groups have expressed challenges in determining if COI is present and how to best manage COI. A variety of approaches are currently being used to determine COI and associated management options, and approaches are not always well documented, leading to concerns about consistency and transparency.

PHAC therefore sought to develop a structured COI assessment tool that can:

- Aid the processes of COI management for groups that work with external bodies of experts

- Be used to consistently and transparently evaluate disclosed interests for the presence of COI, and determine the ideal management approach

- Be flexible and adaptable enough to fit the needs of a variety of groups in different contexts

This tool was informed by an environmental scan of factors used to assess for the presence of COI, as well as approaches to COI management, among the international guideline community. Factors commonly considered in assessing for COI include:

- Relevancy/specificity to the topic[14][13][15][16]

- Recency/currency[13][15][17]

- Frequency of the interest/relationship[15][17]

- Duration and depth of the relationship[13][17]

- Amount (for financial interests)[13][17]

- The role of the individual in the guideline process/decision-making[13][15]

The PHAC tool allows for a structured and transparent assessment of the above factors, to allow the assessor to come to a final judgment about the presence of COI. Use of the tool involves the following steps:

- Interests are disclosed by the expert in the DOI form (see PHAC COI disclosure form for guideline development)

- Info disclosed in forms by experts are input into the tool by the assessor

- Assessor makes a judgment on relevancy and other key considerations

- Based on those factors, a judgment is made on the presence (yes/no) and type of COI (financial, non-financial) and how significant the COI is (low, moderate, high), with the aid of a rubric/algorithm

Figure 2 provides a conceptual schematic of the tool. Detailed instructions for assessing each factor and making judgments on the type and significance of COI are included in the tool.

As noted in Figure 1, when COIs are deemed to be present, the next step is management of those COIs. To facilitate consistent and transparent approaches to managing COI, an algorithm has been developed (Figure 3)to help guide assessors to suggested management options taking into account:

- The type of COI (direct/indirect financial, non-financial)

- The severity of COI (low, moderate high)

- Internationally recognized principles for the management of COI (e.g., GIN[11])

This algorithm to guide users on how to manage COI is included in the COI assessment tool, along with detailed instructions for users.

The full COI assessment tool is currently undergoing pilot testing, and a final tool will be uploaded soon.

Guidelines International Network (GIN) Checklist

The following checklist was developed by PHAC to aid journals seeking to implement the GIN principles on COI for authors, or guideline developers assessing or updating their policies to align with the GIN principles.

A document or link to the document will be uploaded soon.

Resources from the international guideline community

Examples of disclosure of interest forms:

- American Thoracic Society disclosure of interests form

- CADTH pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review disclosure of interest form for panel members

- CADTH pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review disclosure of interest form for clinicians

- CADTH pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review disclosure of interest form for patient groups

- Canadian Task Force on Preventive Healthcare disclosure of interest form (see Appendix 1)

- Cochrane Collaboration disclosure of interest form

- US FDA financial disclosure report – Executive Branch

- US FDA financial disclosure report – Special Government Employees

- National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine disclosure of interest form for general scientific and technical studies and assistance

- National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine disclosure of interest form for studies involving program reviews and evaluations

- National Academies of Science Engineering and Medicine disclosure of interest form for studies related to government regulation

- National immunization technical advisory groups (NITAGs)

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK) disclosure of interest form for advisory committees

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (UK) disclosure of interest form for board members and employees

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) disclosure of interest form for completion by individuals, carers, voluntary organisations and members of the public

- United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) disclosure of interest form

Examples of published summaries of disclosures

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation disclosure summary

- Haute Authorité de Santé (France) examples of public disclosures of experts

Examples of scales for assessing the significance of COI

- American Thoracic Society method for evaluating significance of COI

- World Health Organization criteria for assessing the severity of a conflict of interest (see p. 78)

- USPSTF COI significance and management table

Examples of algorithms/process maps for COI management

- American Thoracic Society COI resolution procedure

- CADTH pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review COI management overview (Appendix A)

- European Medicines Agency COI management matrix

- Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS) diagramme de processus en matière de conflits d’intérêts (Annexe D)

- National Research Council Canada COI flowchart

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (UK) process for declaring interests (Appendix A)

GIN principles paper

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines; Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1990. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK235751/

- ↑ Johnson L, Stricker RB. Attorney General forces Infectious Diseases Society of America to redo Lyme guidelines due to flawed development process. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2009;35:283-288.

- ↑ Lenzer J. French guidelines are withdrawn after court finds potential bias among authors. BMJ. 2011 Jun 24;342:d4007.

- ↑ Howlett, K. Conflicts of interest didn’t influence new opioid standards: review. The Globe and Mail [online]. September 7, 2017. Available from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/conflicts-of-interest-didnt-influence-new-opioid-standards-review/article36199835/

- ↑ Dwyer, D. WHO drops opioid guidelines after criticism of corporate influence. The BMJ. 2019:365. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l4374

- ↑ Cosgrove L, Bursztajn HJ, Erlich DR, Wheeler EE, Shaughnessy AF. Conflict of interest and clinical guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19: 674-681.

- ↑ The Canadian Press. Co-author of controversial meat study did not disclose ties to ‘classic front group’. National Post. October 5, 2019. Available from: https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/scientist-responds-to-critique-of-industry-ties-after-publishing-study-on-red-meat

- ↑ Cohen D, Brown E. Surgeons withdraw support for heart disease advice. BBC Newsnight. December 9, 2019. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/health-50715156.

- ↑ Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers J, Cluzeau F, Feder G, Fervers B, Graham, ID, Grimshaw J, Hanna S, Littlejohns P, Makarski J, Zitzelsberger L on behalf of the AGREE Next Steps Consortium. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. Can Med Assoc J. 2010;182:E839-842.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Reducing and managing conflicts of interest in clinical practice guideline development: do we need Pan-Canadian standards? Government of Canada, 2019. Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51455.html

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Schünemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F, et al. Guidelines International Network: Principles for Disclosure of Interests and Management of Conflicts in Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:548–553.

- ↑ Kelsall D. New CMAJ policy on competing interests in guidelines. CMAJ. 2019; 191(13):E350-351.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development (2nd Edition); Chapter 6 Declaration and management of interest. WHO 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js22083en/

- ↑ Schünemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F, et al. Guidelines International Network: Principles for Disclosure of Interests and Management of Conflicts in Guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:548–553.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Haute Autorité de Santé. Guide des déclarations d’intérêts et de gestion des conflits d’intérêts. HAS 2013 (revised 2017). Available: https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/guide_dpi.pdf (accessed May 15 2019).

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Policy on declaring and managing interest for NICE advisory committees. NICE, April 2018. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/Who-we-are/Policies-and-procedures/declaration-of-interests-policy.pdf (accessed April 4 2019).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Agence de Médecine Préventive. Prevention of Conflicts of Interest in NITAGs: Principles and guidance to implement Conflict of Interest management policy. AMP 2017. Available: http://www.nitag-resource.org/media-center/document/3465 (accessed May 15 2019).