Gettysburg

This page is for the purposes of Canadian Forces College Experiential Learning Visit in support to the Joint Command and Staff Programme.

The American Civil war, 1860-65

Strategic Context

Union victory of the Civil War is credited to Grant and Lincoln's implementation, in 1864, of an overarching strategy that incorporated all aspects of power to achieve results: political, economic, and diplomatic elements as well as military operations. Prior to 1864, Union politics often drove military decisions, with Union generals having unclear guidance and needing to pursue multiple objectives, including destroy Confederate armies, occupy territory, build railroads, and protect supply lines. The Union's 1964 strategy was a collection of complementary activities: Grant's military operations, Republican leadership plans for winning a reelection, and the State Department efforts to increase the Confederacy's isolation. At this time, the Union also determined that the Confederacy's centre of gravity was the support of the Southern population for continuing its war effort. The Confederates arguably determined this before the Union did. One of Lee's reasons for the invading the North in 1863 was to achieve a military victory on Northern soil in order to convince the Northern public that their war was unwinnable.[1]

By 1864, Lincoln had set relatively mild terms for Southern states to return to the Union, which caused debate within the Confederacy whether further resistance would be worse than submission. Concurrently, Union was making economic life difficult for the Confederacy. While the majority of Confederate ports were in Union hand, 84% of ships were successful in running the blockade, a British-supplied blockade. Further, since 1862, the South developed sufficient production facilities of arms and ammunition to negate the dependence on imports. However, the blockade did have two important effects: restriction of luxury goods, creating an impression of hardship for the Southern ruling class; and cessation of access to customs revenues, the primary source of income in the 19th century.[1]

Diplomatically, the Union from the beginning sought to prevent foreign recognition of the Confederacy. US diplomatic missions informed foreign governments that the conflict was not legally a war but an internal dispute. This had the effect of any recognition of the Confederacy being contrary to international law. Further, while there may have been European desire to see the Union broken, the Emancipation Proclamation effectively equated support to the Confederacy with support for slavery, an unacceptable position in most European countries.[1] In contrast, the Confederates were confident that European reliance on Southern cotton and their desire for free trade would elicit full support and therefore, adopted a more passive approach in their foreign policy. Britain and France believed the division of the United States was irrevocable. While they were dependent on cotton, they also had an ample supply in storage and wartime trade with the Union was highly profitable so a European policy of neutrality was adopted. This was only threatened when the combination of Union errors, the actual and feared depletion of cotton stocks, and horror at the death and destruction in America brought Europe to the brink of intervention. Northern diplomacy, military successes and economic dominance ultimately prevented this, which is thought would have brought Confederate success.[2]

Key military factors in the Civil War, which can be seen as dominant in the outcomes at various points of the Gettysburg Campaign:[1]

- doctrine (FE) - the superiority of defense to offense

- organization (FG, FM, FS) - force mass of a scope not seen before

- RMA (FD) - technology such as the telegraph, railways, and rifled musket as well as organization like improved methods of field fortification or "active" entrenched defense that created invulnerability to frontal assaults

The Gettysburg Campaign

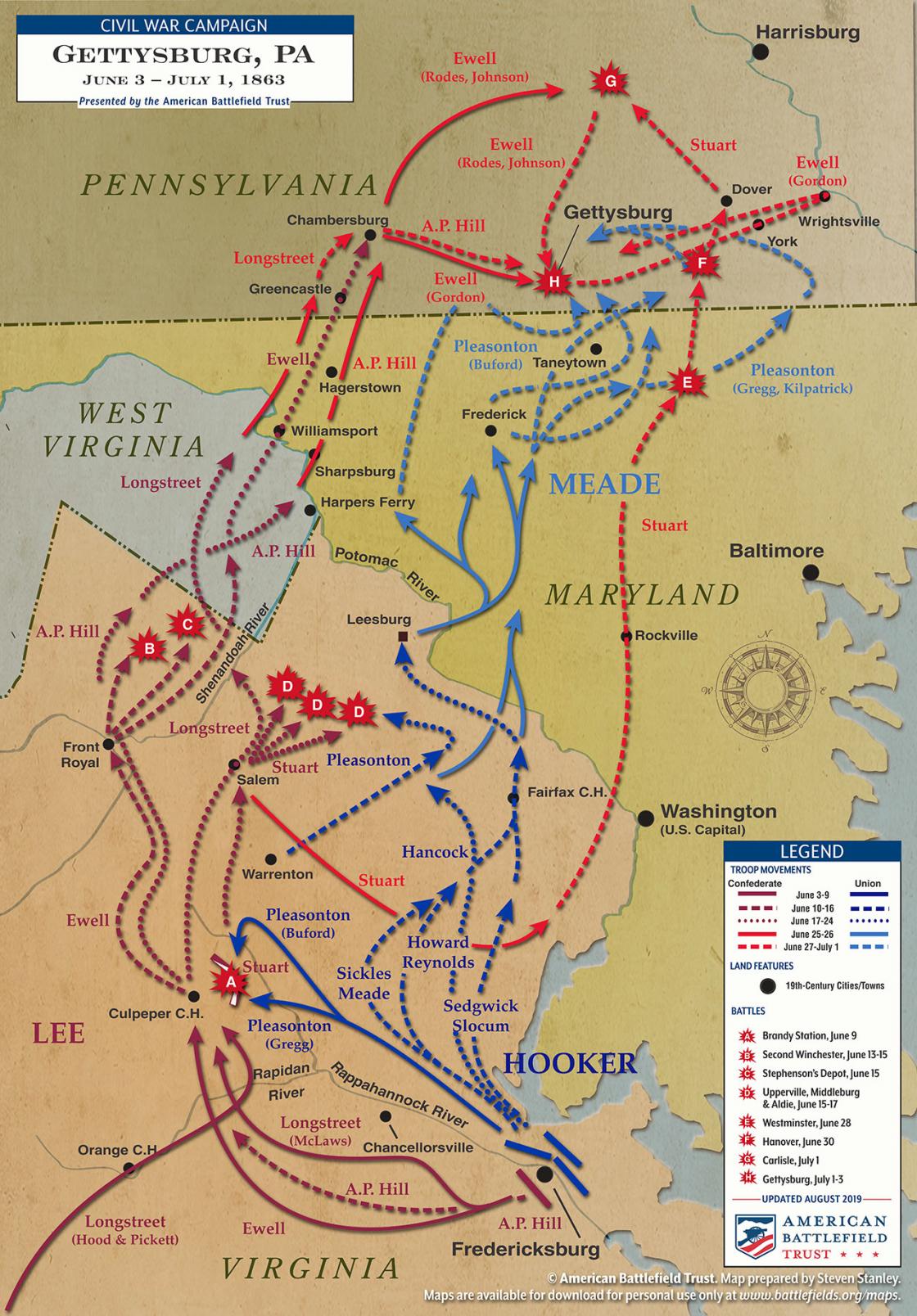

Lee brings the war to the enemy, defeating Union forces at Winchester, Virginia, and then continuing north to Pennsylvania. During the Battle of Gettysburg, Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac, had greater numbers and better defensive positions that led ultimately to its victory over the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. Militarily, the Battle of Gettysburg is considered the high-water mark of the Confederacy but also ended Confederate hopes of formal recognition by foreign governments.[3]

Key Decisions made before and during the Campaign

- Army Level Strategic Decision: Army of Northern Virginia goes north. There were several options at the time: stay in Virginia, join the fighting in the Western Theater, and going across the Potomac River into Northern territory. The last allowed the Army to gather forage and supplies, disrupt Union campaign plans, and potentially gain a political advantage with a battlefield victory. Going North led to the Battle of Gettysburg.

- Army Level Organizational Decision, Artillery:

- For the South, Lee believed the two-corps arrangement was too large for effective control and reorganized his army into three infantry corps, then disbanded the reserve artillery and reassigned its batteries to the corps. The cavalry organization was left as it was for the most part. This change provided greater flexibility for manoeuvering and deploying.

- For the North, the Army of the Potomac reorganized its artillery by designating some to corps level and others to create a large Artillery Reserve. Both infantry and cavalry corps had artillery brigades assigned. The commander of the Artillery Reserve was responsible to the Chief of Artillery who reported directly to the Army commander. This change eliminated many command and supply problems and provided flexibility to distribute artillery fire across a wide front or concentrate it for massed fire on a specific target. On all three days at Gettysburg, the North's new configuration decisively helped blunt Confederate assaults.

- Division Level Operational Decision: MGen Stuart was Lee's cavalry commander who provided intelligence, protected the army's flanks and raided. Prior to Gettysburg, Stuart took his three best of five brigades to ride around the Union army. This left Lee without effective reconnaissance and led to his surprise when he encountered the Army of the Potomac in Pennsylvania.

- Division Level Tactical Decision: MGen Rodes was instructed to not bring on a general engagement but assume a defensive position and wait for the Army of Northern Virginia to concentrate. On 1 July at Oak Ridge, Rodes incorrectly assumed he was on the Army of the Potomac's right flank and attack. After the first attack failed, he launched a second attack. The attacks resulted in four divisions of Lee's army being committed prematurely to battle and a piecemeal deployment of the rest of the army as it arrived. Lee lost the ability to use the full power of his force.

- Corps Level Tactical Decision: Conversely, Ewell did follow Lee's instructions and did not conduct an attack on Cemetery Hill, where the Union had already established a strong defensive position. This allowed the Union to continue to occupy and reinforce Cemetery and Culp's Hill, impacting Lee's offensive options for 2 July.

- Army Level Tactical Decision: For 3 July, the plan to continue attacks on both Union flanks was not tenable so Lee decided to attack the Union centre, a force advancing over open ground in the face of strong defensive fire that came to be known as "Pickett's Charge" and at the cost of extensive casualties. At this point, Lee had lost ~34% of his army from 1-3 July, ammunition was low with no resupply possible north of the Potomac river, water was scarce, and the ability to resupply was severely curtailed. It was decided to withdraw.

Force Management

Force Development

Force Employment

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 https://ndupress.ndu.edu/JFQ/Joint-Force-Quarterly-77/Article/581883/union-success-in-the-civil-war-and-lessons-for-strategic-leaders

- ↑ https://www.americanforeignrelations.com/A-D/Civil-War-Diplomacy.html

- ↑ https://www.loc.gov/collections/civili-war-glass-negatives/articles-and-essays/time-line-of-the-civil-war/1863/