Important: The GCConnex decommission will not affect GCCollab or GCWiki. Thank you and happy collaborating!

Technology Trends/Data Leak Prevention

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Status | Published | ||||||

| Initial release | May 23, 2019 | ||||||

| Latest version | May 23, 2019 | ||||||

| Official publication | Blockchain.pdf | ||||||

| |||||||

Data Leak Prevention (DLP), also known as “data loss prevention,” is a cybersecurity solution that includes a variety of strategies, processes, and tools whose purpose is to protect an organization‘s valuable data from being accessed by unauthorized users, released into an untrusted environment, or destroyed.

Business Brief

DLP provides the tools to mitigate data leak incidents from occurring within an organization. DLP software usually includes the following functionalities:

- Protection: DLP tools implement safeguards such as encryptions, access controls and restrictions to mitigate possible vulnerabilities. An organization can regulate file access by classifying data according to their level of security and by defining a set of rules each user has to abide by.

- Detection: DLP can alert administrators by generating a real-time detailed report on policy violations such as an attacker attempting to access sensitive data. By creating a baseline behavioural profile of standard patterns, the software can detect abnormal or suspicious user activity. Some solutions accomplish this using machine learning.

- Monitoring: DLP monitors the behaviour of users on how the data is being accessed, used and moved through the IT infrastructure in order to detect irregular or dangerous user activity. If an event is triggered by a rule violation, the system will notify the security personnel. The system gains visibility in order to proactively secure data from leaving the organization on policy violations.

Technology Brief

DLP technology is usually categorized into three different components related to each state of the data lifecycle: data at rest, data in motion, and data in use. In most DLP products, there is also a central management server acting as the control center of the DLP deployment. This is usually where DLP policies are managed, data is collected from sensors and endpoint agents, and backup and restore is handled. The components of a data leak prevention tool are, in general:

Storage DLP: “Data at Rest” refers to data stored on a “device,” for example, on a server, database, workstations, laptops, mobile devices, portable storage or removable media. The term refers to data being inactive and not currently being transmitted across a network or being actively processed. A storage DLP protects this type of data by using several security tools:

- Data masking hides sensitive information like personal identifiable data.

- Access controls prevent unauthorized access.

- File encryption adds a layer of protection.

- Data classification uses a DLP agent to tag data according to their level of security. Combined with a set of rules, an organization can regulate user access to use, modify and delete information.

- A database-activity monitoring tool inspects databases, data warehouses (EDW) and mainframes and sends alerts on policy violations. In order to classify data, some mechanism uses conceptual definitions, keywords or regular expression matching.

Network DLP: “Data in Motion” is data that is actively traveling across a network such as email or a file transferred over File Transfer Protocol (FTP) or Secure Socket Shell (SSH). A Network DLP focuses on analyzing network traffic to detect sensitive data transfer in violation of security policies and providing tools to ensure the safety of data transfer. Examples of this include:

- An email monitoring tool can identify if an email contains sensitive information and block the action or encrypt the content.

- The Intrusion Detection System (IDS) monitors for any malicious activity occurring on the network and typically reports to an administrator or to the central management server using a Security Information and Event Management system (SIEM).

- Firewall and antivirus software are commonly available products included in a DLP strategy.

Endpoint DLP: “Data in Use” is the data currently being processed by an application. Data of this nature is in the process of being generated, updated, viewed, and erased on a local machine. Protecting this type of data is a challenging task because of the large number of systems and devices but it is usually done through an Endpoint DLP agent installed on the local machine. Some characteristics are:

- The tool provides strong user authentication, identity management and profile permissions to secure a system.

- It can monitor and flag unauthorized activities that users may intentionally or unintentionally perform, such as print/fax, copy/paste and screen capture.

- Some DLP agents may offer application control to determine which application can access protected data.

- There are advanced solutions that use machine learning and temporal reasoning algorithms to detect abnormal behavior on a local machine.

Industry Usage

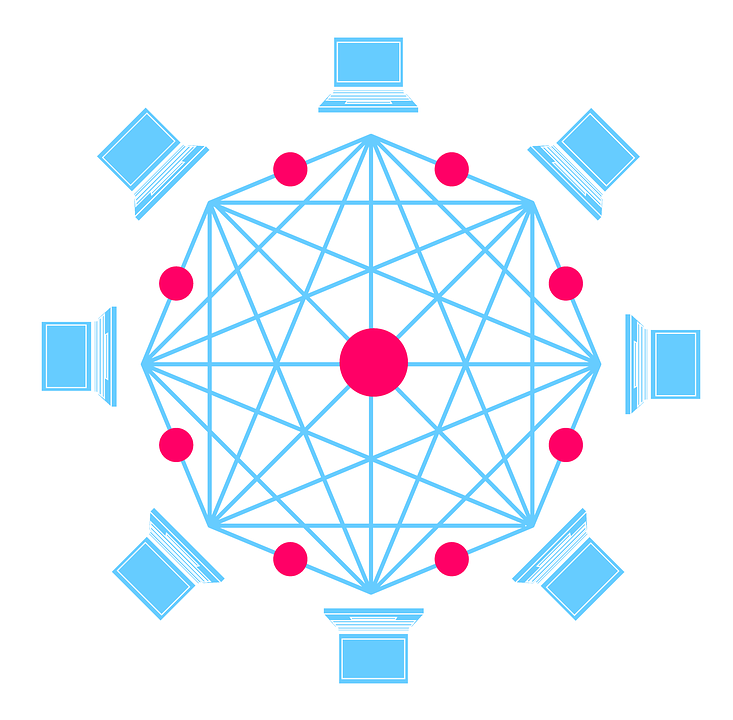

The most well-known use of blockchain is in support of cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin. A digital currency launched in 2009, Bitcoin does not rely on a monetary authority to monitor verify or approve transactions, but rather relies on a peer-to-peer computer network made up of its users’ machines to do that. Blockchain can be used for all sorts of inter-organizational cooperation. In 2017, Harvard Business Review estimated that approximately 15% of banks are expected to be using blockchain.[1]

Although Bitcoin is the first and most well-known use of the blockchain technology, it is only one of about seven hundred applications that use the blockchain distributed ledger system. Blockchain is a digital ledger on top of which organizations can build trusted applications, via a secure chain of custody for digital records.

Canadian Government Use

According to Gartner, there is no Government around the world that is operating a true blockchain initiative , although some (State of Georgia, Hong Kong, United Arab Emirate) are operating pseudo-initiatives and starting to experiment with the technology.[2] Treasury Board of Canada notes highlights a few specific initiatives: Estonia uses an eHealth Foundation partnership to accelerate blockchain-based systems to ensure security, transparency, and auditability of patient healthcare records. Singapore employs the use of blockchain to prevent traders from defrauding banks through a unique distributed ledger-based system focused on preventing invoice fraud.[3]

In 2017, “The Blockchain Corridor: Building an Innovation Economy in the 2nd Era of the Internet” was developed, discussing ways to turn Canada into a global hub for the “Blockchain revolution.” Written by a high-tech think tank and prepared for / partially funded by the federal Department of Innovation, Science and Economic Development (ISED), the report lays out a few proposals regarding how to cement Canada’s role as a world leader in blockchain technology. The Canadian Government announced in July 2017 the intention to run at least 6 select pilot projects on the use of blockchain.[4]

Implications for Government Agencies

Value Proposition

Blockchain offers a numbers of benefits to the Government of Canada, such as a reduction in costs and complexity, trusted record keeping and user-centric privacy control. It offers significant opportunities in terms of a single source for public records, support for multiple contributors and a technology ideal for multi-jurisdictional interactions. Due to its decentralized, collaborative nature, it potentially aligns well with policies and practices around Open Government, which aim to make Government services, data, and digital records more accessible to Canadians.

By eliminating the duplication and reducing the need for intermediaries, blockchain technology could be used by SSC to speed-up aspects of service delivery. A challenge for SSC in terms of blockchain will be to identify which enterprise solutions emerge as leaders and how they deal with privacy, confidentiality, auditability, performance and scalability.

- Elections Canada – practical applications to support Voter List Management, Secure Identity Management, and management of electoral geography.

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada – exploring implications for anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing.

- Public Safety Canada – focused on various uses and misuses of virtual currencies, such as extortion or blackmail.

- Natural Resources Canada – use as a public registry for the disclosure of payments under the Extractive Sectors Transparency Measures Act.

- Bank of Canada – exploring a proof of concept model alongside Payments Canada, Canadian commercial banks and the R3 consortium.

- ISED – engagement with Government departments, provincial-territorial-municipal partners, and key industry players.

Challenges

The amount of time and energy required to maintain the blockchain and create new blocks is not small and this is a frequent criticism of the technology. Conventional database entry, such as using SQL, takes only milliseconds, compared to blockchain, which takes several minutes. Due to the length of time required as well as the need for multiple computers to verify the blocks, blockchains consume an enormous amount of energy.

There are also some concerns with respect to privacy. Since blockchain is built on the premise of decentralization and transparency, the data within the chain is technically available for anyone on the network, provided they have the computational power and knowledge to gain access. Instead of being identified on the network by name, users have encryption keys, which is a list of seemingly random numbers and letters.

Considerations

In a traditional transaction, all stakeholders have to keep a record of the transaction and in the case of a discrepancy, it was more difficult / costly to determine the accuracy of a record. As a result, Blockchain may offer significantly higher returns for each investment dollar spent than that of traditional internal investments. However, to doing so, it means collaborating with customers, citizens, suppliers and competitors in new ways.[8]

Further research is needed to understand the potential impacts that blockchain could have on SSC as a service provider as well on the usage amounts the GC would require. SSC should consider the identification of client areas where blockchain may be leveraged. It may be required that client departments self-identify spaces which could benefit from blockchain processes.

Lastly, SSC and the GC should consider the capacity issues in resources, network capabilities, and time required to create and maintain blockchain networks on its own. Blockchain is not a pedestrian technology, it will require dedicated teams that are appropriately resourced and financed in order for the technology to be deployed as any other service. SSC may wish to consider looking for private sector companies that specialize in providing Blockchain as a Service (BaaS), and determine the risk and cost benefits of outsourcing this process altogether.

Hype Cycle

| English | Français |

|---|---|

| Figure 1. Hype Cycle for Blockchain Technologies, 2018 | Figure 1. Rapport Hype Cycle sur les technologies de la chaîne de blocs, 2018 |

| Expectations | Attentes |

| Time | Temps |

| Blockchain Wallet Platform | Plate-forme de portefeuille de la chaîne de blocs |

| Blockchain Interoperability | Interopérabilité de la chaîne de blocs |

| Postquantum Blockchain | Chaîne de blocs post-quantique |

| Smart Contract Oracle | Oracle des contrats intelligents |

| Zero Knowledge Proofs | Preuve à divulgation nulle de connaissance |

| Distributed Storage in Blockchain | Stockage distribué dans la chaîne de blocs |

| Smart Contracts | Contrats intelligents |

| Blockchain for IAM | Chaîne de blocs pour la gestion des identités et de l’accès |

| Blockchain PaaS | Chaîne de blocs à titre de PaaS |

| Blockchain for Data Security | Chaîne de blocs pour la sécurité des données |

| Decentralized Applications | Applications décentralisées |

| Consensus Mechanisms | Mécanismes de consensus |

| Metacoin Platforms | Plates-formes de Metacoin |

| Sidechains/Channels | Chaînes latérales/canaux |

| Multiparty Computing | Calcul multipartite |

| Cryptocurrency Hardware Wallets | Portefeuilles matériels de cryptomonnaie |

| Cryptocurrency Software Wallets | Portefeuilles logiciels de cryptomonnaie |

| Blockchain | Chaîne de blocs |

| Distributed Ledgers | Grands livres distribués |

| Cryptocurrency Mining | Minage de cryptomonnaie |

| Innovation Trigger | Déclencheur d’innovation |

| Peak of Inflated Exepctations | Pic des attentes exagérées |

| Trough of Disillusionment | Gouffre des désillusions |

| Slope of Enlightenment | Pente de l’illumination |

| Plateau of Productivity | Plateau de productivité |

| As of July 2018 | En date de juillet 2018 |

| Plateau will be reached: | Le plateau sera atteint : |

| Less than 2 years | dans moins de 2 ans |

| 2 to 5 years | dans 2 à 5 ans |

| 5 to 10 years | dans 5 à 10 ans |

| More than 10 years | dans plus de 10 ans |

| Obsolete before plateau | Désuet avant le plateau |

| Source: Gartner (July 2018) | Source : Gartner (juillet 2018) |

References

- ↑ Gupta, V. (28 February 2017). A Brief History of Blockchain. Retrieved on 23 May 2019

- ↑ Gartner conference call.

- ↑ Treasury Board of Canada

- ↑ Secretariat, T. B. (29 March 2019). Digital Operations Strategic Plan: 2018-2022. Retrieved on 23 May 2019

- ↑ Treasury Board of Canada, Blockchain: Ideal Use Cases for the Government of Canada, 5.

- ↑ Vallée, J.-C. L. (April 2018). [Vallée, J.-C. L. (April 2018). Adopting Blockchain to Improve Canadian Government Digital Services. Retrieved on 23 May 2019 Adopting Blockchain to Improve Canadian Government Digital Services]. Retrieved on 23 May 2019

- ↑ Diedrich, H. (2016). Ethereum: Blockchains, Digital Assets, Smart Contracts, Decentralized Autonomous Organizations. Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- ↑ Treasury Board of Canada, Blockchain: Ideal Use Cases for the Government of Canada, 5.