Difference between revisions of "GC Service & Digital Target Enterprise Architecture"

John.currah (talk | contribs) (L’objectif de l'architecture intégrée) |

|||

| (53 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{OCIO_GCEA_Header}} | ||

| + | <multilang> | ||

| + | @en|__NOTOC__ | ||

| − | + | = GC Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture Whitepaper = | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Version: 1.33 | Version: 1.33 | ||

November 4, 2020 | November 4, 2020 | ||

| − | Office of the Chief Information Officer of Canada | + | Office of the Chief Information Officer of Canada, Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, Government of Canada |

| − | |||

| − | Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | ||

| − | |||

| − | Government of Canada | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

=== Executive summary === | === Executive summary === | ||

| Line 60: | Line 37: | ||

This white paper is not meant to replace existing documents that address the government’s strategic direction on digital services. | This white paper is not meant to replace existing documents that address the government’s strategic direction on digital services. | ||

| − | [[Image:Service and Digital Target State Architecture.png|Service_and_Digital_Target_State_Architecture.png]] | + | === Digital government === |

| + | A digital government puts people and their needs first. It is accountable to its citizens and shares information with them. It involves them when making policies and designing services. It values inclusion and accessibility. It designs services for the people who need them, not for the organizations that deliver them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>The Government of Canada is an open and service-oriented organization that operates and delivers programs and services to people and businesses in simple, modern and effective ways that are optimized for digital and available anytime, anywhere and from any device. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Digitally, the Government of Canada must operate as one to benefit each and every Canadian.<ref>Digital Operations Strategic Plan: 2021–2024 - Canada.ca</ref> | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === ''Policy on Service and Digital'' === | ||

| + | The ''Policy on Service and Digital'' and supporting instruments serve as an integrated set of rules that articulate how Government of Canada organizations manage service delivery, information and data, information technology, and cybersecurity in the digital era. Other requirements, including but not limited to, requirements for privacy, official languages and accessibility, also apply to the management of service delivery, information and data, information management and cybersecurity. Those policies, set out in Section 8, must be applied in conjunction with the ''Policy on Service and Digital''. The ''Policy on Service and Digital'' focuses on the client, ensuring proactive consideration at the design stage of key requirements of these functions in the development of operations and services. It establishes an enterprise‑wide, integrated approach to governance, planning and management. Overall, the ''Policy on Service and Digital'' advances the delivery of services and the effectiveness of government operations through the strategic management of government information and data and leveraging of information technology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Section 4.1.2.3 of the ''Policy on Service and Digital''. The Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Canada is responsible for: Prescribing expectations with regard to enterprise architecture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Section 4.1.2.4 of the ''Policy on Service and Digital''. The Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Canada is responsible for: Establishing and chairing an enterprise architecture review board that is mandated to define current and target architecture standards for the Government of Canada and review departmental proposals for alignment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Section 4.1.1.1 of the ''Directive on Service and Digital''. The departmental Chief Information Officer (CIO) is responsible for: Chairing a departmental architecture review board that is mandated to review and approve the architecture of all departmental digital initiatives and ensure their alignment with enterprise architectures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === What problems does the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture address? === | ||

| + | Canadians rely on the federal government for programs and services, which in turn depend on reliable, authoritative data and enabling information technology capabilities to ensure successful delivery. The GC enterprise ecosystem consists of all the information technology used by the Government of Canada and all related environmental factors. The interdependence of all elements with the ecosystem is an essential aspect of what makes it an ecosystem. When discussing information technology within the GC enterprise, one must consider the ecosystem. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== '''What is the issue?''' ==== | ||

| + | The Government of Canada has reached a critical point in its management of the IT systems that are used to enable the delivery of government services. There is an increasing gap between the expectations of Canadian citizens and the ability of the government’s legacy systems to meet those expectations. The total accumulated technical debt associated with legacy systems has reached a tipping point where a simple system‑by‑system replacement approach for individual systems has increasingly become cost and risk prohibitive. The business processes in place to manage the life cycles of these IT systems have become barriers rather than enablers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== '''How did we get here?''' ==== | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Changing expectations''' | ||

| + | |The rapid evolution of the internet as the ubiquitous platform for service delivery has outstripped the government’s ability to address the demand. Citizens have an increased expectation that all government services will be reliably delivered 24 hours a day, 7 days a week with no artificial differentiation based on which department provides the service. The introduction of new disruptive technologies outside of government can quickly shift the citizen’s expectations as they become aware of new approaches or capabilities. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Separate mandates''' | ||

| + | |Government information systems have long mirrored the legislative separation of the functional mandates of departments. In part, this is because the original approaches to a delegation of authority and accountability in legislation did not contemplate the cross‑cutting dependency on information technology that exists today. Beyond authority and accountability, there are legislative constraints on intragovernmental information sharing has historically impeded the integration of business processes across government. Budget and funding models have further reinforced this separation. As a result, there have been limited opportunities to reduce overhead and eliminate redundancies across systems and across government. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Evolution of technology''' | ||

| + | |Initially, business process automation within government was implemented as standalone solutions, in many cases monolithic and mainframe solutions. As time passed, the life cycle evolution of individual systems tended to limit their scope to those individual systems; reinforced by a desire to restrict procurement, technical, and change complexity and risk. Current technologies that could be used to implement cohesive enterprise approaches were introduced relatively recently, many years after most government systems were implemented. This gap has been exacerbated over time by the significant difference between the ability of the private sector and the public sector to adopt and leverage new technologies. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== '''Why is the problem so intractable? Why isn’t “business as usual” a workable way forward?''' ==== | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''“Business as usual” not effective''' | ||

| + | |The “business‑as‑usual” approach would be to try to address each legacy system in isolation; in other words, a simplistic system‑by‑system replacement. The costs and risks associated with this approach for major legacy systems are prohibitive in most cases. Dealing with each system in isolation results in missed opportunities for reuse and for eliminating redundancies. In addition, these “big bang” methods dramatically increase business service delivery risk. By the time a significant replacement project is completed, there is also a substantial possibility that the underlying technology is out of date. To mitigate these issues, approaches that allow for an incremental and managed transition over time are suggested. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''An alternative strategy''' | ||

| + | |One alternative strategy is to incrementally migrate legacy systems by gradually replacing functional elements with new applications and services; in other words, an “evolve‑and‑transcend” strategy. This strategy implements an architectural pattern named the “Strangler Fig,” a metaphor for refactoring rather than replacing legacy systems, by incrementally replacing functional parts of a legacy application slowly and systematically over time, thus spreading costs and mitigating risks. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture === | ||

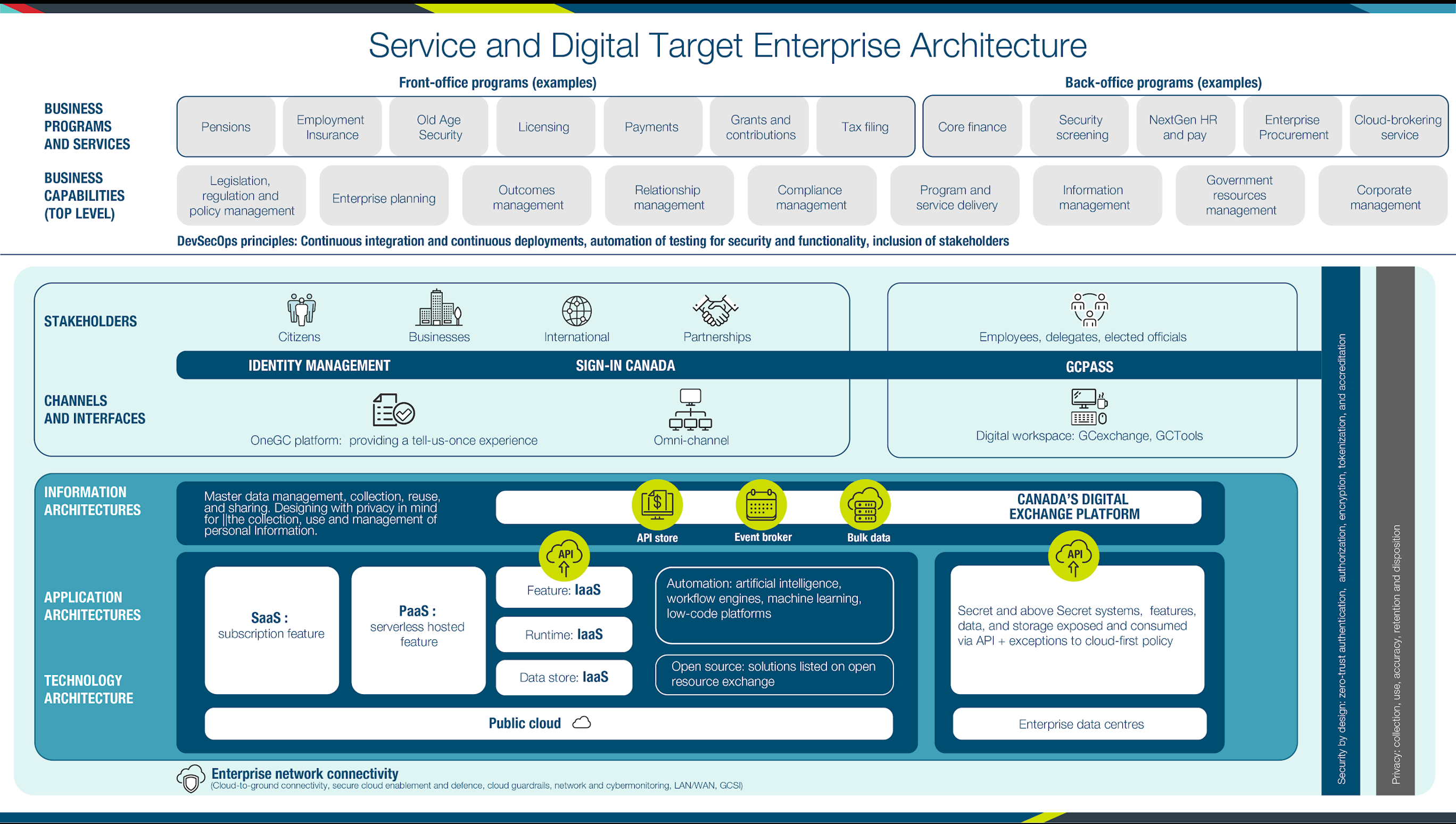

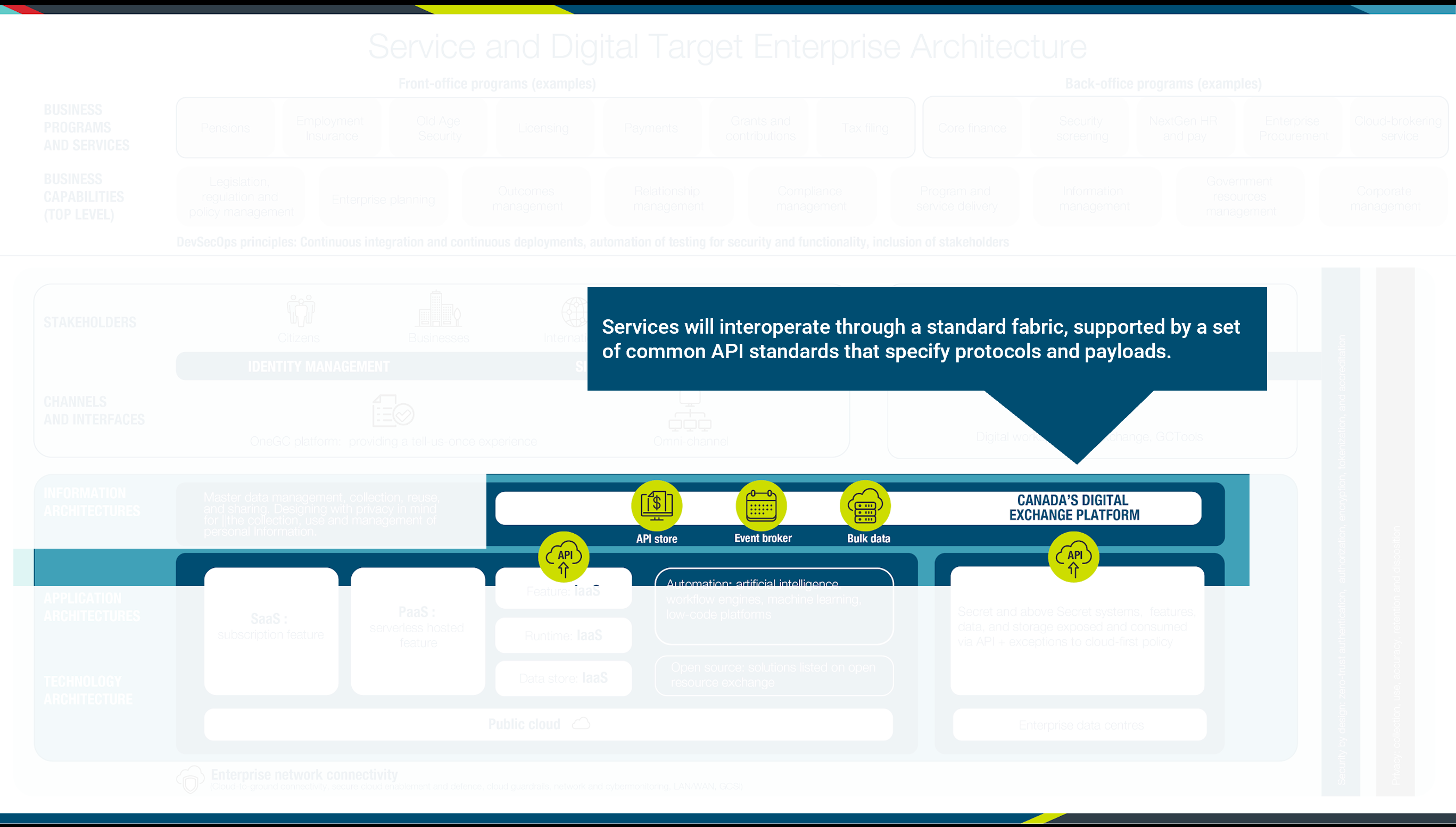

| + | The Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture defines a model for the digital enablement of Government of Canada services that address many of the critical challenges with the current GC enterprise ecosystem. It seeks to reduce the silos within the current GC ecosystem by having departments adopt a user‑ and service‑delivery‑centric perspective when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. It advocates a whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned to business services and solutions are based on reusable components implementing business capabilities optimized to reduce unnecessary redundancy. This reuse is enabled using published APIs shared across government. This approach allows the government to focus on improving its service delivery to Canadians while addressing the challenges with legacy systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Service and Digital Target State Architecture-vJun2021.png|Service_and_Digital_Target_State_Architecture-vJun2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="Text Version" data-collapsetext="Hide Text Version"> | ||

| + | <div class="sidetable"> | ||

| + | <table class="wikitable"> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td> | ||

| + | <h1> | ||

| + | Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture - Text version | ||

| + | </h1> | ||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td> | ||

| + | <p>The top row of the diagram shows examples of business programs and services, divided into two categories: front-office and back-office. </p> | ||

| + | <p>Examples of front-office business programs and services:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Pensions</li> | ||

| + | <li>Employment Insurance</li> | ||

| + | <li>Licensing</li> | ||

| + | <li>Payments</li> | ||

| + | <li>Grants and contributions</li> | ||

| + | <li>Tax filing</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Examples of back-office programs and services:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Core finance (FMT)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Security screening</li> | ||

| + | <li>NextGen HR and Pay</li> | ||

| + | <li>Enterprise procurement</li> | ||

| + | <li>Cloud-brokering service</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>The second row of the architecture shows the top‑level business capabilities:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Legislation, regulation and policy management</li> | ||

| + | <li>Enterprise planning</li> | ||

| + | <li>Outcomes management </li> | ||

| + | <li>Relationship management </li> | ||

| + | <li>Compliance management</li> | ||

| + | <li>Program and service delivery</li> | ||

| + | <li>Information management </li> | ||

| + | <li>Government resources management</li> | ||

| + | <li>Corporate management </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>The third row lists the DevSecOps principles: Continuous integration and continuous deployments, automation of testing for security and functionality, inclusion of stakeholders</p> | ||

| + | <p>The fourth row identifies the various stakeholders: </p> | ||

| + | <p>Externally, examples include:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Citizens</li> | ||

| + | <li>Businesses</li> | ||

| + | <li>International</li> | ||

| + | <li>Partnerships</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Internally, examples include:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Employees, delegates, elected officials </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Two examples of user authentication are presented under the external stakeholder:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Identity management </li> | ||

| + | <li>Sign-in Canada</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>A third example related to the internal stakeholders is GCPass. </p> | ||

| + | <p>The fifth row identifies channels and interfaces.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Externally accessible solution examples are:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>OneGC platform: providing a tell-us-once experience</li> | ||

| + | <li>Omni-channel </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>The third example is related to internal users:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Digital workspace: GCexchange, GCTools</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>The next part of the graphic show the elements of the information architecture, application architecture and technology architecture. </p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Information architecture</strong></p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>For example, master data management, privacy (protection of personal data) </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Canada’s Digital Exchange Platform offers the following capabilities:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>API store</li> | ||

| + | <li>Event broker </li> | ||

| + | <li>Bulk data </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Application architecture </strong>is divided into two categories based on security requirements:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>SaaS subscription feature</li> | ||

| + | <li>PaaS serverless hosted feature</li> | ||

| + | <li>IaaS broken into three parts: | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Feature: IaaS</li> | ||

| + | <li>Runtime: IaaS</li> | ||

| + | <li>Data store: IaaS</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Automations can be achieved through tools such as: | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>artificial intelligence</li> | ||

| + | <li>workflow engines</li> | ||

| + | <li>machine learning</li> | ||

| + | <li>low‐code platforms</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Open source: solutions listed on open resource exchange</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>The information from these application architecture options is shared back to the <strong>Canada’s Digital Exchange Platform</strong> via APIs (application programming interfaces).</p> | ||

| + | <p>Secret and above Secret systems, features, data, and storage exposed and consumed via API plus exceptions to cloud-first policy.</p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Technology architecture</strong></p> | ||

| + | <p>Public cloud is the recommended architecture for solutions that are considered Protected B or below from an identified security level.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Solutions above Protected B must use Enterprise Data Centres. </p> | ||

| + | <p>All the layers of the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture rely on <strong>enterprise network connectivity</strong>.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Examples of enterprise network connectivity include:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Cloud-to-ground connectivity</li> | ||

| + | <li>secure cloud enablement and defence </li> | ||

| + | <li>cloud guardrails</li> | ||

| + | <li>network and cybermonitoring</li> | ||

| + | <li>LAN/WAN </li> | ||

| + | <li>GCSI </li> | ||

| + | <li>Related business continuity infrastructure</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Along the right side of the graphic are two overarching principles:</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Security by design: zero-trust authentication, authorization, encryption, tokenization and accreditation</li> | ||

| + | <li>Privacy: collection, use, accuracy, retention, and disposition</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | |||

| + | </tr> | ||

| + | </table> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | <br/> | ||

| + | The goal of the Service and Digital Target State Enterprise Architecture is to depict the Government of Canada’s future state in one picture. The diagram is divided into several parts, which are based on The Open Architecture Framework (TOGAF) framework explained in a subsequent section. This framework views business, information and data, applications, technology and security each as separate layers, having their own concerns and architecture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The top layer of the diagram represents business architecture. The programs in this layer are categorized as front office, which provides services directly to citizens, academic institutions, and Canadian businesses, and back‑office services which support the government itself. Examples of front office programs include Employment Insurance and tax filing services, and examples of back‑end programs include finance security screening, pay, enterprise procurement, and business continuity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the following layer, key aspects of the top level of the GC Business Capability Model are depicted. This takes into consideration the IT plan investment framework and provides a mechanism to identify potentially redundant investments across, opportunities for rationalization, and identification of opportunities for enterprise solutions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Align_with_DOSP-vJune2021.png|SandD_Align_with_DOSP-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

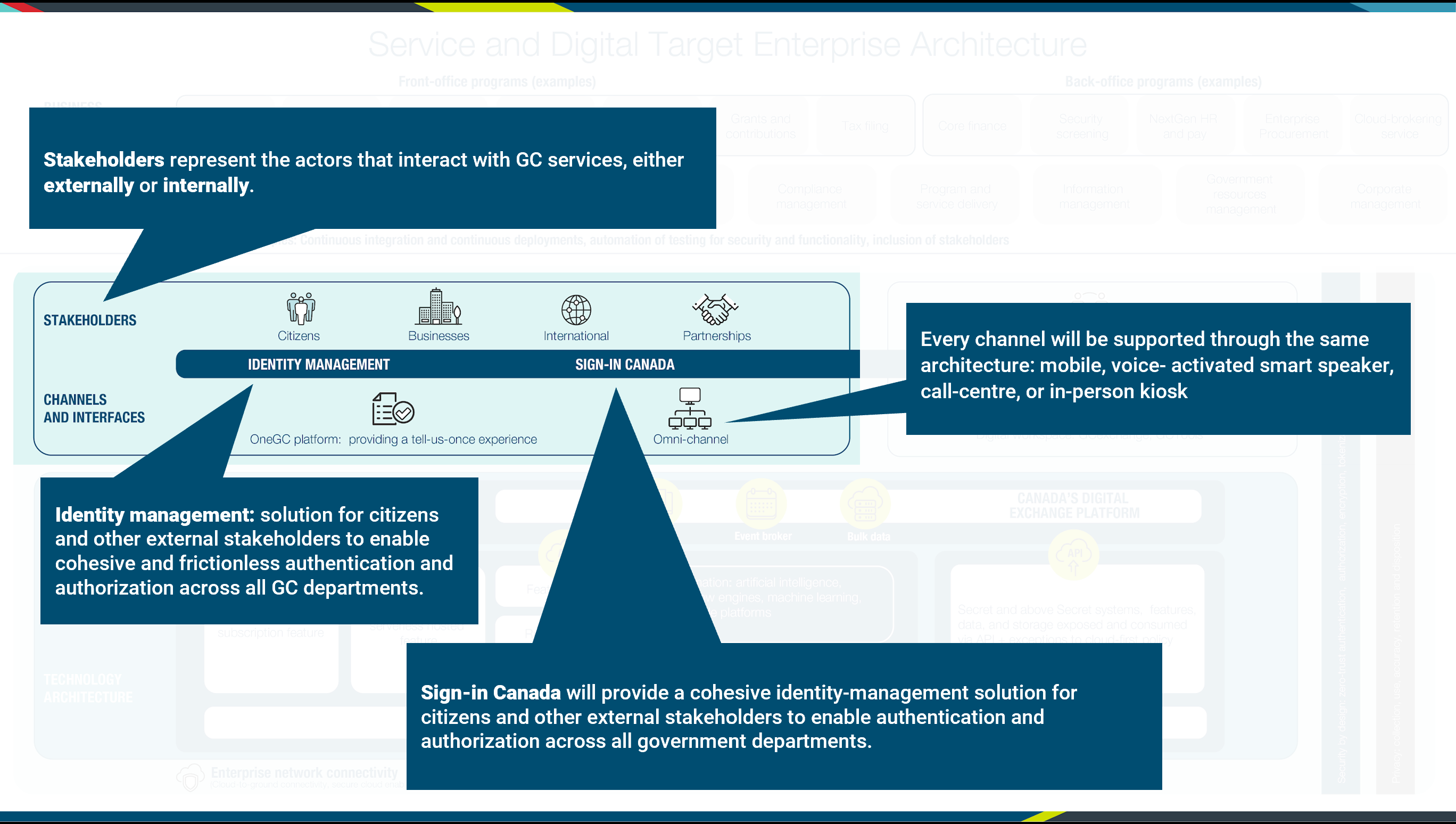

| + | In the following layer, stakeholders represent the actors that interact with GC services, either externally (such as citizens, businesses, those which the GC is in partnership with such as universities or international actors), or internally, such as GC employees, delegates, or elected officials. They have different access (use of mobile, voice‑activated smart speakers, contact centres, and kiosks) and accessibility requirements, and may communicate in either official language. Sign‑in Canada will provide a cohesive identity management solution for citizens and other external stakeholders to enable authentication and authorization across all GC departments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The goal is to respond to external users, who as clients, want interactions across governments to be managed with consistency, integrity, and trust so that they have a beneficial, personalized, and seamless experience. | ||

| + | |||

| + | To ensure consistency, every channel will be supported through the same architecture. Examples of these channels include mobile, voice‑activated smart speaker, call centre, or in‑person kiosk. This concept is called omni‑channel. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The next layer projects the idea of a service‑oriented government, with a user‑centred approach to the business of government that puts citizens and their needs as the primary focus of our work, using “tell‑us‑once” service approaches, integrated services across the GC program and service landscape in a way that provides real‑time information to Canadians about their service applications. It is a perspective centred on users and service delivery when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. It builds on business architecture guidance to design for users first, focusing on the needs of users, using agile, iterative, and user‑centred methods in a whole-of-government context. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_External_Stakeholders-vJune2021.png|SandD_External_Stakeholders-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Leveraging the concept of harmonization described for external users through Sign‑in Canada, GCPass will enable authentication and authorization to GC Systems for Internal stakeholders. The digital workplace will uniformly enable the work of public servants, building on a standard design. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Internal_Stakeholders-vJune2021.png|SandD_Internal_Stakeholders-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

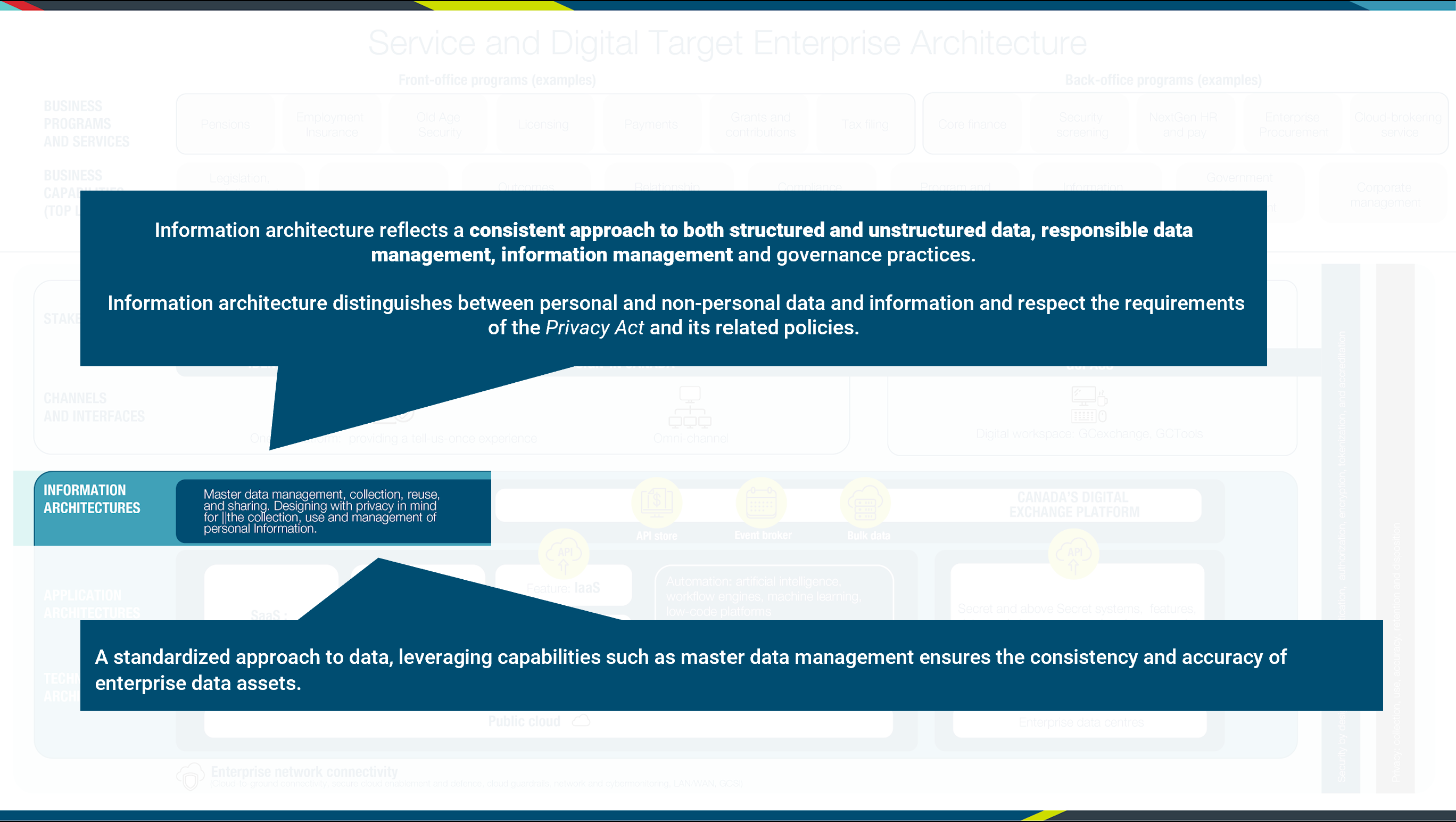

| + | Information architecture is depicted in the following layer. Information architecture best practices and principles aim to support the needs of a business service and business capability orientation. To facilitate effective sharing of data and information across government, information architectures should be designed to reflect a consistent approach to data, such as the adoption of federal and international standards. Information architecture should also reflect responsible data management, information management and governance practices, including the source, quality, interoperability, and associated legal and policy obligations related to the data assets. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Information architectures should also distinguish between personal and non‑personal data and information as the collection, use, sharing (disclosure), and management of personal information must respect the requirements of the ''Privacy Act'' and its related policies. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Information_Architecture-vJune2021.png|SandD_Information_Architecture-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

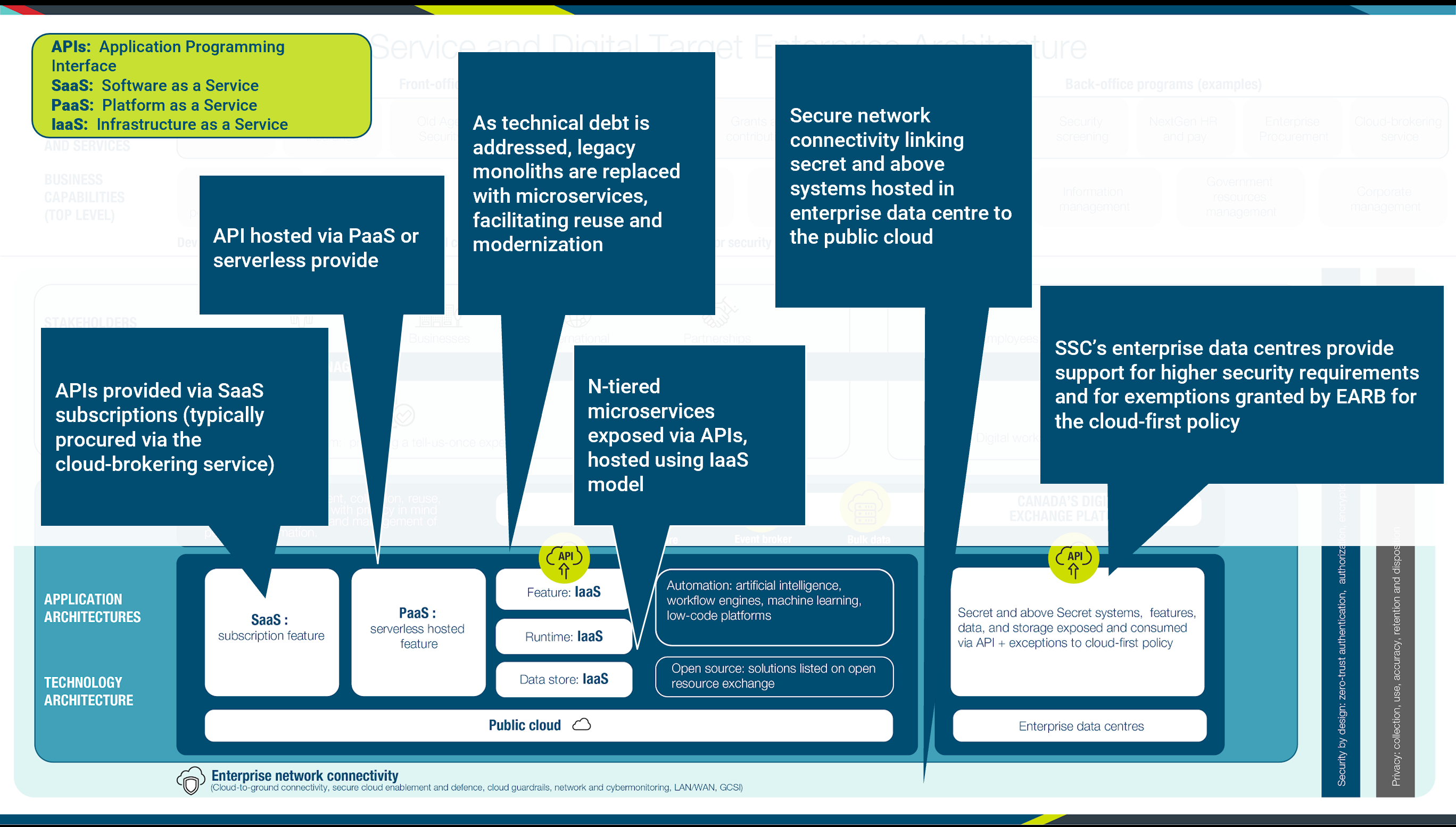

| + | The following layer depicts how services will interoperate through a standard fabric, supported by a set of common API standards specifying protocols and payloads. These services will be published in the API Store to facilitate reuse. APIs will be brokered through an API gateway to manage traffic, ensure version control, and monitor how services are exposed and consumed, either directly, or through a common event broker. Procurement of software as a service (SaaS) offerings will be facilitated through Shared Services Canada’s (SSC’s) Cloud Brokering Service and supported through their managed services. These are services that are available to steward infrastructure that are offered by SSC include database management services, cabling, facility management, transition planning and support, system integration services, and project management, among others. GC business programs and services and their enabling capabilities are built on resources within the application and information landscapes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Interop-vJune2021.png|SandD_Interop-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Also highlighted in this layer are automation capabilities such as artificial intelligence and open source solutions listed on an open resource exchange. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Application_Architecture_and_Technical_Architecture-vJune2021.png|SandD_Application_Architecture_and_Technical_Architecture-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

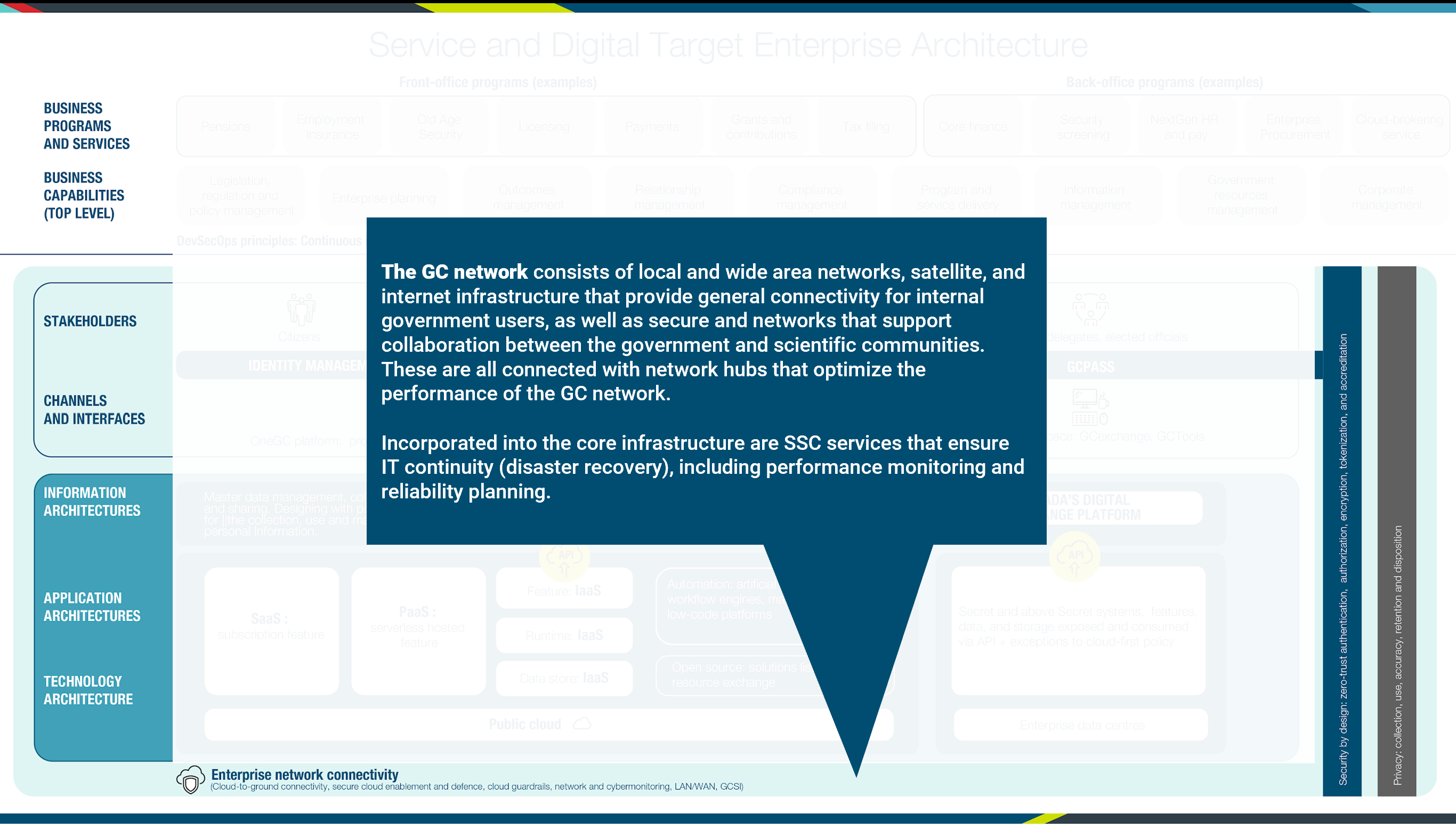

| + | In the bottom‑most view of the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture, the focus is on the technology infrastructure that acts as the glue to bring everything together: the network. The GC network consists of local area network (LAN), wide area network (WAN), satellite, and internet infrastructure that provides general connectivity for internal government users, as well as secure and networks that support collaboration between the government and scientific communities. These are all connected with network hubs that optimize the performance of the GC network. The core infrastructure includes SSC services that ensure IT continuity (disaster recovery), including performance monitoring and reliability planning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Enterprise_Network_Connectivity-vJune2021.png|SandD_Enterprise_Network_Connectivity-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Security is reflected in the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture diagram as a cross‑cutting factor that spans all horizontal layers. The goal is to ensure security at all architectural levels, from design to implementation to operations; and to ensure authentication, authorization, auditing, monitoring, tokenization, and encryption of all data, whether at rest or in motion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:SandD_Security_Architecture-vJune2021.png|SandD_Security_Architecture-vJune2021.png|frameless|900px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Improved outcomes === | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Improved digital services that meet citizens’ expectations''' | ||

| + | |Canadian citizens expect reliable digital services that deliver a cohesive user experience. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Their expectation for cohesive user experience is founded on their perception that digital services are being delivered by “one” government and not a collection of departments. By aligning digital service delivery to a common set of services defined within a GC Service Inventory and implemented using reusable components based on a common taxonomy of business capabilities, GC can improve the user experience. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Their expectations for reliability and availability are based on their experiences with modern private‑sector internet services. By transitioning to public cloud offerings and infrastructure, GC can leverage private sector investments to meet citizens’ expectations for reliability and availability. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Managed costs and improved agility''' | ||

| + | |GC needs to achieve economies of scale realized by modernizing and standardizing IT and by reducing its reliance on costly and outdated technology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By encouraging the sharing of reusable components based on business capabilities and by leveraging private sector cloud solutions and open source software, GC can both reduce redundancy and help manage costs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By transitioning to an architecture that leverages public cloud offerings and infrastructure, GC can become more agile in responding to changes in business needs, thus delivering future‑ready IT systems that can support the GC digital transformation journey. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Engaged and effective workforce''' | ||

| + | |Retention has been identified as a significant IT workforce and talent management issue. The ability to attract and retain new talent is challenging due to the perception that government IT is decades out‑of‑date. Besides the drain on workforce capacity, attrition has negatively impacted morale, the level of engagement and overall workforce effectiveness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By adopting modern technology and practices, the government is in a better position to attract and retain new talent. Reducing attrition and boosting recent talent acquisition will have a positive impact on morale and foster an engaged and effective workforce. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Realization practices and principles === | ||

| + | To realize the GC Enterprise Ecosystem Target Architecture, departments should align with the practices and principles as outlined below, when considering new IT solutions or modernizing older solutions. The architectural approach was developed to facilitate managed incremental transitions but requires more strategic planning on the part of departments to be implemented effectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Government of Canada Enterprise Architecture Framework defined below presents the evaluation criteria being used by GC Enterprise Architecture Review Board to align solutions to the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture. In the interest of effective communication to the architecture community of practice, the material has been organized based on the architectural domains business, information, application, technology, and security. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Enterprise architecture framework === | ||

| + | The enterprise architecture framework is the criteria used by the Government of Canada enterprise architecture review board and departmental architecture review boards when reviewing digital initiatives to ensure their alignment with enterprise architectures across business, information, application, technology and security domains to support strategic outcomes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Business architecture ==== | ||

| + | Business architecture is a critical aspect for the successful implementation of the GC Enterprise Ecosystem Target Architecture. The architectural strategy advocates whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned to business services and solutions are based on re‑useable components implementing business capabilities in order to deliver a cohesive user experience. As such, it is essential that business services, stakeholder needs, opportunities to improve cohesion and opportunities for reuse across government be clearly understood. In the past these elements have not been a priority. It is expected that the IT culture and practices will have to change to make business architecture, in general, and these elements a primary focus. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Design services digitally from end‑to‑end to meet the Government of Canada users and other stakeholders’ needs''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * clearly identify internal and external users and other stakeholders and their needs for each policy, program and business service | ||

| + | * include policy requirement applying to specific users and other stakeholder groups, such as accessibility, gender-based plus analysis, and official languages in the creation of the service | ||

| + | * perform Algorithmic Impact Assessment (AIA) to support risk mitigation activities when deploying an automated decision system as per ''Directive on Automated Decision-Making'' | ||

| + | * model end‑to‑end business service delivery to provide quality, maximize effectiveness and optimize efficiencies across all channels (for example, lean process) | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Architect to be outcome‑driven and strategically aligned to the department and to the Government of Canada''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * identify which departmental/GC business services, outcomes and strategies will be addressed | ||

| + | * establish metrics for identified business outcomes throughout the life cycle of an investment | ||

| + | * translate business outcomes and strategy into business capability implications in the GC Business Capability Model to establish a common vocabulary between business, development, and operation | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Promote horizontal enablement of the enterprise''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * identify opportunities to enable business services horizontally across the GC enterprise and to provide cohesive experience to users and other stakeholders | ||

| + | * reuse common business capabilities, processes and enterprise solutions from across government and private sector | ||

| + | * publish in the open all reusable common business capabilities, processes and enterprise solutions for others to develop and leverage cohesive horizontal enterprise services | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Information architecture ==== | ||

| + | Information architecture includes both structured and unstructured data. The best practices and principles aim to support the needs of a business service and business capability orientation. To facilitate effective sharing of data and information across government, information architectures should be designed to reflect a consistent approach to data, such as the adoption of federal and international standards. Information architecture should also reflect responsible data management, information management and governance practices, including the source, quality, interoperability, and associated legal and policy obligations related to the data assets. Information architectures should also distinguish between personal and non‑personal data and information as the collection, use, sharing (disclosure), and management of personal information must respect the requirements of the ''Privacy Act'' and its related policies. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Collect data to address the needs of the users and other stakeholders''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * assess data requirements‑based program objectives, as well users, business and stakeholder needs | ||

| + | * collect only the minimum set of data needed to support a policy, program, or service | ||

| + | * reuse existing data assets where permissible and only acquire new data if required | ||

| + | * ensure data collected, including from third-party sources, are of high quality | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Manage and reuse data strategically and responsibly''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * define and establish clear roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities for data management | ||

| + | |||

| + | * identify and document the lineage of data assets | ||

| + | * define retention and disposition schedules in accordance with business value as well as applicable privacy and security policy and legislation | ||

| + | * ensure data are managed to enable interoperability, reuse and sharing to the greatest extent possible within and across departments in government to avoid duplication and maximize utility, while respecting security and privacy requirements | ||

| + | * contribute to and align with enterprise and international data taxonomy and classification structures to manage, store, search and retrieve data | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Use and share data openly in an ethical and secure manner''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * share data openly by default as per the ''Directive on Open Government and Digital Standards'', while respecting security and privacy requirements; data shared should adhere to existing enterprise and international standards, including on data quality and ethics | ||

| + | * ensure data formatting aligns to existing enterprise and international standards on interoperability; where none exist, develop data standards in the open with key subject matter experts | ||

| + | * ensure that combined data does not risk identification or re‑identification of sensitive or personal information | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Design with privacy in mind for the collection, use and management of personal Information''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * ensure alignment with guidance from appropriate institutional ATIP Office with respect to interpretation and application of the ''Privacy Act'' and related policy instruments | ||

| + | * assess initiatives to determine if personal information will be collected, used, disclosed, retained, shared, and disposed | ||

| + | * only collect personal information if it directly relates to the operation of the programs or activities | ||

| + | * notify individuals of the purpose for collection at the point of collection by including a privacy notice | ||

| + | * personal information should be, wherever possible, collected directly from individuals but can be from other sources where permitted by the ''Privacy Act'' | ||

| + | * personal information must be available to facilitate Canadians’ right of access to and correction of government records | ||

| + | * design access controls into all processes and across all architectural layers from the earliest stages of design to limit the use and disclosure of personal information | ||

| + | * design processes so personal information remains accurate, up‑to‑date and as complete as possible, and can be corrected if required | ||

| + | * de‑identification techniques should be considered prior to sharing personal information | ||

| + | * in collaboration with appropriate institutional ATIP Office, determine if a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) is required to identify and mitigate privacy risks for new or substantially modified programs that impact the privacy of individuals | ||

| + | * establish procedures to identify and address privacy breaches so they can be reported quickly and responded to efficiently to appropriate institutional ATIP Office | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Application architecture ==== | ||

| + | Application architecture practices must evolve significantly for the successful implementation of the GC Enterprise Ecosystem Target Architecture. Transitioning from legacy systems based on monolithic architectures to architectures that oriented around business services and based on re‑useable components implementing business capabilities, is a major shift. Interoperability becomes a key element, and the number of stakeholders that must be considered increases. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Use open source solutions''' | ||

| + | '''hosted in public cloud''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * select existing solutions that can be reused over custom built | ||

| + | * contribute all improvements back to the communities | ||

| + | * register open source software to the Open Resource Exchange | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Use software as a service (SaaS)''' | ||

| + | '''hosted in public cloud''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * choose SaaS that best fit for purpose based on alignment with SaaS capabilities | ||

| + | * choose a SaaS solution that is extendable | ||

| + | * configure SaaS and if customization is necessary extend as open source modules | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Design for Interoperability''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * design systems as highly modular and loosely coupled services | ||

| + | * expose services, including existing ones, through APIs | ||

| + | * make the APIs discoverable to the appropriate stakeholders | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Technology architecture ==== | ||

| + | Technology architecture is an important enabler of highly available and adaptable solutions that must be aligned with the chosen application architecture. Cloud adoption provides many potential advantages by mitigating the logistical constraints that often negatively impacted legacy solutions hosted “on premises.” However, the application architecture must be able to enable these advantages. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Use cloud first''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * adopt the use of the GC Accelerators to ensure proper security and access controls | ||

| + | * enforce this order of preference: software as a service (SaaS) first, then platform as a service (PaaS), and lastly infrastructure as a service (IaaS) | ||

| + | * fulfill cloud services through SSC Cloud‑Brokering Services | ||

| + | * enforce this order of preference: public cloud first, then hybrid cloud, then private cloud, and lastly non‑cloud (on‑premises) solutions | ||

| + | * design for cloud mobility and develop an exit strategy to avoid vendor lock‑in | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Design for performance, availability and scalability''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * ensure response times meet user needs, and critical services are highly available | ||

| + | * support zero‑downtime deployments for planned and unplanned maintenance | ||

| + | * use distributed architectures, assume failure will happen, handle errors gracefully, and monitor performance and behaviour actively | ||

| + | * establish architectures that supports new technology insertion with minimal disruption to existing programs and services | ||

| + | * control technical diversity; design systems based on modern technologies and platforms already in use | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Follow DevSecOps principles''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * use continuous integration and continuous deployments | ||

| + | * ensure automated testing occurs for security and functionality | ||

| + | * include your users and other stakeholders as part of the DevSecOps process, which refers to the concept of making software security a core part of the overall software delivery process | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== Security architecture ==== | ||

| + | The GC Enterprise Security Architecture program is a government‑wide initiative to provide a standardized approach to developing IT security architecture, ensuring that basic security blocks are implemented across the enterprise as the infrastructure is being renewed. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Build security into the system life cycle across all architectural layers''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * identify and categorize information based on the degree of injury that could be expected to result from a compromise of its confidentiality, integrity and availability | ||

| + | * implement a continuous security approach, in alignment with Centre for Cyber Security’s IT Security Risk Management Framework; perform threat modelling to minimize the attack surface by limiting services exposed and information exchanged to the minimum necessary | ||

| + | * apply proportionate security measures that address business and user needs while adequately protecting data at rest and data in transit | ||

| + | * design systems to be resilient and available in order to support service continuity | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Ensure secure access to systems and services''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * identify and authenticate individuals, processes or devices to an appropriate level of assurance, based on clearly defined roles, before granting access to information and services; leverage enterprise services such as Government of Canada trusted digital identity solutions that are supported by the Pan‑Canadian Trust Framework | ||

| + | * constrain service interfaces to authorized entities (users and devices), with clearly defined roles; segment and separate information based on sensitivity of information, in alignment with ITSG‑22 and ITSG‑38. Management interfaces may require increased levels of protection | ||

| + | * implement HTTPS for secure web connections and Domain-based Message Authentication, Reporting and Conformance (DMARC) for enhanced email security | ||

| + | * establish secure interconnections between systems through secure APIs or leveraging centrally managed hybrid IT connectivity services | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Maintain secure operations''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | * establish processes to maintain visibility of assets and ensure the prompt application of security‑related patches and updates in order to reduce exposure to vulnerabilities, in accordance with GC ''Patch Management Guidance'' | ||

| + | * enable event logging, in accordance with GC ''Event Logging Guidance'', and perform monitoring of systems and services in order to detect, prevent, and respond to attacks | ||

| + | * establish an incident management plan in alignment with the GC Cyber Security Event Management Plan (GC CSEMP) and report incidents to the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === GC enterprise ecosystem transition === | ||

| + | The realization of the Target Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture involves dozens of departments and thousands of applications and will involve many interim states. The technical strategy is to incrementally migrate legacy systems by gradually replacing functional elements with new applications and services thus spreading costs and mitigating risks. However, the fundamental nature of the change required demands more than just a technical strategy. To meet Canadians’ expectations for coherent digital service delivery, the government must modernize its policy and practices to support the technological transition to the target enterprise architecture. | ||

| + | [[File:Service and Digital transition chevrons.png|center|thumb|595x595px]] | ||

| + | Significant progress has already been made, particularly around enabling policy, and work has begun on changing practices, but much work remains. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Enabling policy and regulation === | ||

| + | To support the change needed, the enabling policy and regulation must be aligned with the strategic direction. The policy must support the required changes and not be a barrier to adoption. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Integrated policy and directive to enable change''' | ||

| + | |Treasury Board approved a new ''Policy on Service and Digital'' and ''Directive on Service and Digital'', which serve as an integrated set of rules that articulate how Government of Canada organizations manage service delivery, information and data, information technology and cybersecurity in the digital era. TBS, through the Office of the Chief Information Officer, developed guidance informed by departmental feedback, reviewed existing Treasury Board policy instruments and identified emerging areas. | ||

| + | * enhanced and integrated governance with an Enterprise Approach | ||

| + | * increased focus on the client and the digital enablement across all services and channels | ||

| + | * better use and sharing of information recognizing its value as a strategic asset | ||

| + | * leverage technology to better manage and protect systems and information | ||

| + | * strengthen and train the federal workforce to meet the needs of a digital government | ||

| + | TBS, through the Office of the Chief Information Officer, and departments will continue to update guidance and evolve Treasury Board policy instruments. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === GC enterprise focused practices === | ||

| + | The proposed strategies and architectural principles are significant departures from past practices. Existing departmental practices for the management of IT have locked the government into a cycle that reinforces siloed approaches. The emphasis must shift from isolation and control to collaboration and sharing with the focus on cohesive service delivery to citizens rather than individual mandates. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''GC Target Enterprise Architecture''' | ||

| + | |The Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture provides a framework and focal point for making informed decisions on the alignment of business solutions to GC needs. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''GC Enterprise Architecture Framework''' | ||

| + | |Business, information, application, technology, security, and privacy architecture domains defined by the GC to align solutions to the Service and Digital Target Enterprise Architecture. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''GC Enterprise Architecture Review Board (GC EARB)''' | ||

| + | |The GC Enterprise Architecture Review Board (GC EARB) provides a governance mechanism to assess if proposed solutions are aligned to the GC Enterprise Architecture Framework. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Establishment of GC Enterprise Portfolio Management (GC EPM)''' | ||

| + | |GC Enterprise Portfolio Management (GC EPM) will support integrated planning, prioritization, and optimization of an achievable enterprise investment portfolio by enabling the integration of critical processes and data to inform decision‑making, visibility, and transparency. | ||

| + | * Alignment: ensuring that all investments, services, and applications are aligned to GC strategy | ||

| + | * Collaboration: reducing the burden and balancing the portfolio by ensuring the right work is being completed at the right time | ||

| + | * Visibility: accessible information provides stakeholders visibility on delivery capacity and enhances oversight and reporting | ||

| + | * Decision‑making: prioritization allows for informed decision‑making while offering the opportunity to re‑balance the portfolio | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Including the business capability perspective in the IT plan''' | ||

| + | |The inclusion of Business Capability Model mapping in the IT plan investment framework provides another mechanism to identify potentially redundant investments in business capabilities across government and opportunities for rationalization and to identify opportunities for enterprise solutions. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Including the application capability perspective in the Application Portfolio Management''' '''framework''' | ||

| + | |The inclusion of Application Capability Model mapping into the GC Application Portfolio Management framework provides another mechanism to identify overlapping application capabilities and unused functions. Reducing the technology footprint will decrease operational expenses and free up funds for other priorities. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''GC Cloud Brokering''' | ||

| + | |The GC Cloud Brokering provides a way for departments to obtain public cloud services already vetted. It simplifies the procurement and fulfillment of cloud services by providing a unified process for requesting cloud services that have been thoroughly investigated and approved to comply with the requirements of the GC, as well as to offer central agencies with the visibility of all environments in the cloud. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''API store''' | ||

| + | |The API store provides a mechanism to publish reusable business capabilities and access to data. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Open source software''' | ||

| + | |The Open Source Policy and White Paper guided the use of software, the need for contribution to open source software, the publishing of open source software, and the acquisition of open source software. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Digital workspace standards and profiles''' | ||

| + | |GC EARB created standards for internal enterprise services, defined digital workspace user profiles, set departmental consumption of IT services, and sets consumption metrics and limits for each of SSC’s 31 services. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Framework for Government‑Wide Data Governance and Stewardship''' | ||

| + | |GC EARB introduced a government‑wide framework for data governance and stewardship, for TBS work on the development of principles, policies and guidance concerning “prescribing enterprise‑wide data standards.” | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === GC enterprise IT ecosystem === | ||

| + | The government has made some limited progress in common application capabilities such as document management and others. However, the predominantly monolithic architectures of departmental applications have effectively limited sharing and reuse across government. The transition towards the GC Target Enterprise Architecture is needed to achieve progress in that area. | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''GC enterprise solutions''' | ||

| + | |The establishment of GC enterprise solutions has provided a standard implementation for common application capabilities such as document management (GCDOCS), collaboration (GCshare), and Customer Relationship Management CRM (GCcase). | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''GC enterprise digital workplace platform''' | ||

| + | |The acquisition of Office 365 provides a secure cloud‑based, software‑as‑a‑service solution for the digital workspace. Its rollout will provide a coherent user experience across government over multiple devices and channels. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Sign‑in Canada''' | ||

| + | |Sign‑in Canada is a proposal for a unified authentication mechanism for all government digital engagement with citizens. Users would only need to tell Sign‑in Canada one time who they are, and subsequently, there would be no need to sign up multiple times to access different government services. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''GC internal authentication''' | ||

| + | |Internally within the government, GCPass, when fully implemented, will provide streamlined secure and appropriate access to GC systems for public servants. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Canadian Geospatial Platform''' | ||

| + | |Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) is launching the Canadian Geospatial Platform (CGP) as the next evolution of the Federal Geospatial Platform, with the transition to a new architecture for a GC enterprise platform that will enable NRCan to host solutions from other GC departments in a platform‑as‑a‑service model. CGP will continue to be aligned with the principles of open government and open data and thus is currently configured for unclassified data only. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Summary === | ||

| + | The Government of Canada is responding to the challenge of meeting Canadian citizens’ evolving expectations for cohesive digital service delivery in the face of aging IT systems and rising technical debt. To meet this challenge, the government is changing the way it approaches acquiring new solutions and modernizing older solutions. By advocating a whole‑of‑government approach where IT is aligned to business services, and solutions are based on reusable components implementing business capabilities optimized to reduce unnecessary redundancy, it is maintaining a clear focus on improving its service delivery to Canadians while addressing the technical challenges with its legacy systems. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The future digital landscape of the Government of Canada will be more agile in responding to changes in business needs and better able to leverage new disruptive technologies. Significant progress has already been made, particularly in enabling policy, and work has begun on changing practices, but much work remains. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An ongoing commitment is needed from everyone involved in digital service delivery to be engaged and active participants in these changes by adopting: | ||

| + | * a service‑centric perspective; and focusing on delivering a cohesive user experience for our citizens | ||

| + | * a business capability‑centric perspective when considering solutions, and embracing sharing and reuse | ||

| + | * a whole‑of‑government perspective; and embracing change | ||

| + | This white paper is just another small step of the larger journey. | ||

| + | |||

| + | @fr|__NOTOC__ | ||

| + | |||

| + | = Architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique Livre blanc = | ||

| + | |||

| + | Version : 1.33 | ||

| + | Le 4 novembre 2020 | ||

| + | Bureau du dirigeant principal de l’information du Canada | ||

| + | Secrétariat du Conseil du Trésor du Canada | ||

| + | Gouvernement du Canada | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Résumé === | ||

| + | Gouvernement du Canada | ||

| + | |||

| + | L’architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique est un catalyseur pour la ''Politique sur les services et le numérique''. | ||

| + | L’architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique définit un modèle pour l’habilitation numérique des services du GC qui visent à répondre à plusieurs des défis pressants avec l’écosystème d’entreprise actuel du GC. Elle cherche à abolir le cloisonnement au sein de l’écosystème actuel du GC en invitant les ministères à adopter une perspective axée sur l’utilisateur et la prestation de services lorsque de nouvelles solutions de TI sont envisagées ou des solutions plus anciennes sont modernisées. Elle préconise une approche pangouvernementale où les TI sont harmonisées avec les services opérationnels et les solutions sont fondées sur des composantes réutilisables mettant en œuvre des capacités opérationnelles qui sont optimisées de manière à réduire la redondance. Cette réutilisation est rendue possible au moyen d’interfaces de programmation d’applications (IPA) qui sont partagées dans l’ensemble du gouvernement. Cette approche permet au gouvernement de mettre l’accent sur l’amélioration de sa prestation de services aux Canadiens tout en relevant les défis liés aux anciens systèmes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | La ''Politique sur les services et le numérique'' et l’architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique sont dictés par l’engagement de respecter les principes directeurs et les pratiques exemplaires des Normes numériques du gouvernement du Canada : | ||

| + | * Concevoir avec les utilisateurs | ||

| + | * Effectuer régulièrement des itérations et des améliorations | ||

| + | * Travailler ouvertement par défaut | ||

| + | * Utiliser des normes et des solutions ouvertes | ||

| + | * Gérer les risques en matière de sécurité et de protection des renseignements personnels | ||

| + | * Intégrer l’accessibilité dès le départ | ||

| + | * Permettre au personnel d’offrir de meilleurs services | ||

| + | * Être de bons gestionnaires de données | ||

| + | * Concevoir des services éthiques | ||

| + | * Collaborer à grande échelle | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Objet du présent document === | ||

| + | Ce document vise à aider les institutions fédérales en formulant des recommandations sur la façon dont les systèmes peuvent être mis en œuvre au cours des prochaines années pour offrir aux citoyens canadiens un paysage numérique plus cohérent et plus durable lorsqu’ils interagissent avec le gouvernement du Canada. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Le public visé est constitué des membres qui participent à la prestation de services numériques au sein du gouvernement du Canada, y compris les administrateurs généraux et les dirigeants principaux de l’information. Le livre blanc informera également les fournisseurs de l’orientation de l’architecture intégrée, les aidant à harmoniser leurs services lorsqu’ils interagissent avec le gouvernement. Enfin, le livre blanc informera le public canadien et la communauté internationale de l’orientation de l’architecture intégrée du gouvernement du Canada pour la transition numérique. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sauf avis contraire, aucun des exemples mentionnés dans ce livre blanc ne représente des plans actuels du gouvernement du Canada. | ||

| + | Ce livre blanc ne vise pas à remplacer les documents actuels qui traitent de l’orientation stratégique du gouvernement en matière de services numériques. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Le gouvernement numérique === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Le gouvernement numérique accorde la priorité aux citoyens et à leurs besoins. Il est responsable devant ses citoyens et partage les renseignements avec eux. Il les implique dans l’élaboration des politiques et la conception des services. Il valorise l’inclusion et l’accessibilité. Il conçoit des services pour les personnes qui en ont besoin, et non pour les organisations qui les fournissent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>Le gouvernement du Canada est une organisation ouverte et orientée vers les services qui offre des programmes et des services aux citoyens et aux entreprises de manières simples, modernes et efficaces qui sont optimisés pour la voie numérique et disponibles n’importe quand, n’importe où et sur n’importe quel appareil. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Le gouvernement du Canada doit se comporter numériquement de façon uniforme afin que tous les Canadiens puissent en profiter | ||

| + | <ref>Plan stratégique des opérations numériques : de 2021 à 2024</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | === ''Politique sur les services et le numérique'' === | ||

| + | La ''Politique sur les services et le numérique'' et les instruments d’appui constituent un ensemble intégré de règles qui décrit la façon dont les organisations du GC gèrent la prestation de services, l’information et les données, la technologie de l’information et la cybersécurité à l’ère du numérique. D’autres exigences, qui comprennent sans toutefois s’y limiter, les exigences en matière de confidentialité, de langues officielles et d’accessibilité, s’appliquent également à la gestion de la prestation des services, de l’information, et des données, de la technologie de l’information et de la cybersécurité. Ces politiques, énoncées à la section 8, doivent être appliquées en combinaison avec la ''Politique sur les services et le numérique''. La ''Politique sur les services et le numérique'' est axée sur les clients, ce qui assure des considérations proactives à l’étape de la conception des exigences principales associées à ces fonctions dans l’élaboration des opérations et des services. Elle met en place une approche pangouvernementale intégrée à l’égard de la gouvernance, de la planification et de la gestion. En général, la ''Politique sur les services et le numérique'' fait progresser la prestation des services et l’efficacité des opérations du gouvernement grâce à la gestion stratégique des renseignements et des données du gouvernement et à l’exploitation de la technologie de l’information. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Section 4.1.2.3 de la ''Politique sur les services et le numérique''. Le DPI du Canada est responsable : de prescrire les attentes en matière d’architecture intégrée. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Section 4.1.2.4 de la ''Politique sur les services et le numérique''. Le DPI du Canada est responsable : d’établir et de présider un conseil d’examen de l’architecture intégrée ayant pour mandat de définir les normes d’architecture actuelles et ciblées au profit du gouvernement du Canada et d’effectuer l’examen des propositions ministérielles en matière d’harmonisation. | ||

| + | S | ||

| + | ection 4.1.1.1 de la Directive sur les services et le numérique. Le DPI du Ministère est responsable de ce qui suit : de présider un conseil d’examen de l’architecture dont le mandat est de revoir et d’approuver l’architecture de toutes les initiatives numériques ministérielles, et d’assurer leur harmonisation avec les architectures intégrées. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Quels sont les problèmes auxquels l’architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique vise à répondre? === | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pour les programmes et les services, les Canadiens comptent sur le gouvernement, lui-même dépendant de données fiables et faisant autorité ainsi que d’un accès aux capacités de TI rendant possible la prestation de ces programmes et services. L’écosystème d’entreprise du GC comprend toutes les technologies de l’information utilisées par le GC et tous les facteurs environnementaux connexes. L’interdépendance de tous les éléments avec l’écosystème est un aspect essentiel de ce qui en fait un écosystème. Dans le cadre de discussions sur la technologie de l’information dans l’organisation du GC, on doit tenir compte de l’écosystème. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== '''Quel est le problème?''' ==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Le GC a atteint une étape critique dans sa gestion des systèmes TI qui sont utilisés pour permettre la prestation des services gouvernementaux. Il existe un écart croissant entre les attentes des citoyens canadiens et la capacité des systèmes existants du gouvernement à répondre à ces attentes. La dette technique totale accumulée associée aux systèmes existants a atteint un point de bascule où une approche simple de remplacement, système par système, pour chaque système, est devenue de plus en plus inabordable et risquée. Les processus opérationnels en place pour gérer les cycles de vie de ces systèmes TI sont devenus des obstacles plutôt que des facilitateurs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== '''Comment en sommes-nous arrivés là?''' ==== | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''Attentes changeantes''' | ||

| + | |L’évolution rapide d’Internet en tant que plateforme omniprésente pour la prestation de services a dépassé la capacité du gouvernement de répondre à la demande. Les citoyens s’attendent de plus en plus à ce que tous les services gouvernementaux soient fournis de façon fiable 24 heures sur 24, 7 jours sur 7, sans différenciation artificielle en fonction du ministère qui fournit le service. L’introduction de nouvelles technologies déstabilisantes à l’extérieur du gouvernement peut rapidement modifier les attentes des citoyens aussitôt qu’ils prennent connaissance des nouvelles approches ou capacités. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Mandats distincts''' | ||

| + | |Les systèmes d’information gouvernementaux reflètent depuis longtemps la distinction législative des mandats fonctionnels des ministères. Cela s’explique en partie par le fait que les anciennes approches en matière de délégation de pouvoirs et d’obligation redditionnelle ne tenaient pas compte de la dépendance transversale à l’égard des technologies de l’information qui existe aujourd’hui. Outre l’autorité et la responsabilité, il existe des contraintes législatives sur le partage d’informations intragouvernemental qui ont, dans le passé, nui à l’intégration des processus opérationnels dans l’ensemble du gouvernement. Les modèles de budget et de financement ont encore renforcé cette séparation. Par conséquent, il n’y a eu que peu d’occasions de réduire les frais généraux et d’éliminer les redondances entre les systèmes et au sein du gouvernement. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Évolution de la technologie''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | Au départ, les processus opérationnels automatisés étaient mis en œuvre au sein du gouvernement en tant que solutions autonomes, et dans de nombreux cas, en tant que solutions monolithiques et principales. Au fil du temps, l’évolution du cycle de vie des systèmes individuels a eu tendance à limiter leur portée, renforcée par une volonté de limiter l’approvisionnement, la complexité technique et de changer la complexité et les risques. Les technologies actuelles qui pourraient être utilisées pour mettre en œuvre des approches intégrées ont été introduites relativement récemment, bien des années après la mise en œuvre de la plupart des systèmes gouvernementaux. Cet écart a été exacerbé au fil du temps par la différence appréciable entre la capacité du secteur privé et celle du secteur public à adopter et à tirer parti des nouvelles technologies. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==== '''Pourquoi le problème est-il si insurmontable? Pourquoi le « maintien du statu quo » n’est-il pas une solution viable?''' ==== | ||

| + | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| + | |'''“Le « maintien du statu quo » n’est pas efficace''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | L’approche de « maintien du statu quo » consisterait à essayer de considérer chaque système existant de façon isolée; en d’autres termes, il s’agirait d’une approche simpliste en matière de remplacement de système. Dans la plupart des cas, les coûts et les risques associés à cette approche pour les principaux systèmes existants sont prohibitifs. Le fait de traiter chaque système de manière isolée entraîne des opportunités manquées de réutilisation et d’élimination des redondances. De plus, ces coups d’éclat augmentent considérablement le risque lié à la prestation des services aux entreprises. Au moment où un important projet de remplacement est terminé, il existe aussi une possibilité substantielle que la technologie sous-jacente soit désuète. Afin d’atténuer ces enjeux, des approches permettant une transition progressive et contrôlée au fil du temps sont suggérées. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |'''Une stratégie de rechange''' | ||

| + | | | ||

| + | Une stratégie de rechange consiste à migrer progressivement les systèmes existants en remplaçant progressivement les éléments fonctionnels par de nouvelles applications et de nouveaux services, en d’autres mots, une stratégie « évoluer et transcender ». Cette stratégie met en œuvre un motif architectural appelé « figuier étrangleur », une métaphore désignant le remaniement plutôt que le remplacement des anciens systèmes, en remplaçant progressivement et systématiquement les composantes fonctionnelles d’une ancienne application au fil du temps dans le but de répartir les coûts et d’atténuer les risques. | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique === | ||

| + | L’architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique définit un modèle pour l’habilitation numérique des services du gouvernement du Canada qui visent à répondre à plusieurs des défis pressants concernant l’écosystème d’entreprise actuel du GC. Elle cherche à abolir le cloisonnement au sein de l’écosystème actuel du GC en demandant aux ministères d’adopter une perspective axée sur l’utilisateur et la prestation de services lorsqu’ils envisagent de nouvelles solutions de TI ou lorsqu’ils modernisent des solutions plus anciennes. Elle préconise une approche pangouvernementale où les TI sont harmonisées avec les services opérationnels et les solutions prennent appui sur des composantes réutilisables mettant en œuvre des capacités opérationnelles qui sont optimisées de manière à réduire la redondance. Cette réutilisation est rendue possible au moyen d’IPA qui sont partagées dans l’ensemble du gouvernement. Cette approche permet au gouvernement de se concentrer sur l’amélioration de sa prestation de services aux Canadiens tout en relevant les défis liés aux anciens systèmes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Service and Digital Target State Architecture-vJun2021_fr.png|Service_and_Digital_Target_State_Architecture-vJun2021_fr.png|frameless|900px|Architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="mw-collapsible mw-collapsed" data-expandtext="Afficher la version textuelle" data-collapsetext="Cacher la version textuelle"> | ||

| + | <div class="sidetable"> | ||

| + | <table class="wikitable"> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td> | ||

| + | <h1> | ||

| + | Architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique - Version textuelle | ||

| + | </h1> | ||

| + | </td> | ||

| + | <tr> | ||

| + | <td> | ||

| + | <p>La couche supérieure du diagramme présente des exemples de programmes et de services opérationnels, répartis en deux catégories : les services de première ligne et les services administratifs.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Exemples de programmes et de services opérationnels de première ligne :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Pensions</li> | ||

| + | <li>Assurance-emploi</li> | ||

| + | <li>Délivrance de permis</li> | ||

| + | <li>Paiements</li> | ||

| + | <li>Subventions et contributions</li> | ||

| + | <li>Déclaration de revenus</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Exemples de programmes et de services administratifs :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Activités financières principales (TGF)</li> | ||

| + | <li>Filtrage de sécurité</li> | ||

| + | <li>Prochaine génération des RH et de la paye</li> | ||

| + | <li>Approvisionnement intégré</li> | ||

| + | <li>Service de courtage en matière d’informatique en nuage</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>La seconde couche de l’architecture présente les capacités opérationnelles de premier niveau :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion des lois, des règlements et des politiques</li> | ||

| + | <li>Planification organisationnelle</li> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion des résultats </li> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion des relations </li> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion de la conformité</li> | ||

| + | <li>Prestation des programmes et des services</li> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion de l’information </li> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion des ressources du gouvernement</li> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion ministérielle </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>La troisième couche présente les principes DevSecOps : Intégration continue et déploiements continus, automatisation des essais pour la sécurité et la fonctionnalité, inclusion des intervenants</p> | ||

| + | <p>La quatrième couche présente les différents intervenants : </p> | ||

| + | <p>Exemples d’intervenants externes :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Citoyens</li> | ||

| + | <li>Entreprises</li> | ||

| + | <li>International</li> | ||

| + | <li>Partenariats</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Exemples d’intervenants internes :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Employés, délégués, représentants élus.</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Deux exemples d’authentification des utilisateurs dans la catégorie des intervenants externes :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Gestion de l’identité </li> | ||

| + | <li>Connexion Canada (Authenti-Canada)</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Le troisième exemple concerne les intervenants internes : GCpass.</p> | ||

| + | <p>La cinquième couche présente les canaux et les interfaces.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Exemples de solutions accessibles à l’externe :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Plateforme UnGC : offrir une expérience « Une fois suffit »</li> | ||

| + | <li>Omnicanal </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Le troisième exemple concerne les utilisateurs internes :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Espace de travail numérique : gcéchange, OutilsGC</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>La portion suivante du graphique présente les éléments de l’architecture de l’information, de l’architecture des applications et de l’architecture technologique.</p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Architecture de l’information </strong></p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Par exemple, la gestion des données de base, la confidentialité (protection des données personnelles) </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>La plateforme d’échange numérique canadienne offre les capacités suivantes :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Magasin des API</li> | ||

| + | <li>Courtier en événements </li> | ||

| + | <li>Données en bloc </li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>L’<strong>architecture des applications</strong> est divisée en deux catégories en fonction des exigences de sécurité :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>SaaS : fonctionnalité d’abonnement</li> | ||

| + | <li>PaaS : fonctionnalité d’hébergement sans serveur</li> | ||

| + | <li>L’infrastructure comme service (IaaS) est divisée en trois parties : | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Fonctionnalité : IaaS</li> | ||

| + | <li>Exécution : IaaS</li> | ||

| + | <li>Stockage des données : IaaS</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Les automatisations peuvent être réalisées au moyen d’outils tels que : | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>l’intelligence artificielle</li> | ||

| + | <li>les moteurs de déroulement des opérations</li> | ||

| + | <li>l’apprentissage automatique</li> | ||

| + | <li>les plateformes à peu de codes</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li>Source ouverte : solutions inscrites à l’Échange de ressources ouvert</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>L’information provenant de ces options de l’architecture des applications est transmise à la <strong>plateforme d’échange numérique canadienne</strong> par l’intermédiaire des interfaces de protocole d’application (API).</p> | ||

| + | <p>Systèmes, fonctionnalités, données et stockage classifiés au niveau Secret ou plus et consommés via l’API, et exceptions à la Politique sur l’Informatique en nuage d’abord.</p> | ||

| + | <p><strong>Architecture technique </strong></p> | ||

| + | <p>Le nuage public est l’architecture recommandée pour les solutions qui sont considérées comme Protégé B ou inférieures à un niveau de sécurité déterminé.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Les solutions de niveau supérieur à Protégé B doivent utiliser les centres de données intégrées.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Toutes les couches de l’architecture intégrée cible des services et du numérique reposent sur la <strong>connectivité réseau intégrée</strong>.</p> | ||

| + | <p>Exemples de connectivité réseau intégrée :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Connectivité entre le nuage et le sol</li> | ||

| + | <li>Activation et défense du nuage sécurisé </li> | ||

| + | <li>Mesures de protection du nuage</li> | ||

| + | <li>Surveillances des réseaux et cybersurveillance</li> | ||

| + | <li>RL/RE </li> | ||

| + | <li>ISGC </li> | ||

| + | <li>Infrastructure connexe de continuité des activités</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | <p>Le côté droit du graphique présente deux principes fondamentaux :</p> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>La sécurité à la conception : authentification, autorisation, cryptage, utilisation de jetons et accréditation.</li> | ||