Difference between revisions of "E-signature Options 2020-04"

(Redirected page to E-Signatures in the GC/E-Signature Options Blog 2020-04) Tags: New redirect Visual edit |

|||

| (23 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | #REDIRECT [[E-Signatures in the GC/E-Signature Options Blog 2020-04]]{{DISPLAYTITLE:E-Signatures in the GC/E-signature Options 2020-04}} | ||

<multilang> | <multilang> | ||

@en|__NOTOC__ | @en|__NOTOC__ | ||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

At LoA 1, a user can type her name at the bottom of an email or doc. ument to indicate acceptance of conditions described above in the document or authorization for some purpose. We would recommend that the typed name be marked specially and that the context provided by the wording preceding the signature help make the purpose of the signature clear. Some jurisdictions have adopted a unique format to the typed signature such as | At LoA 1, a user can type her name at the bottom of an email or doc. ument to indicate acceptance of conditions described above in the document or authorization for some purpose. We would recommend that the typed name be marked specially and that the context provided by the wording preceding the signature help make the purpose of the signature clear. Some jurisdictions have adopted a unique format to the typed signature such as | ||

| − | + | <code> | |

| − | /s/ Michael Brownlie (described here: [https://www.cand.uscourts.gov/cases-e-filing/cm-ecf/preparing-my-filing/signatures-on-e-filed-documents/ United States District Court (Northern California)]) | + | /s/ Michael Brownlie</code> (described here: [https://www.cand.uscourts.gov/cases-e-filing/cm-ecf/preparing-my-filing/signatures-on-e-filed-documents/ United States District Court (Northern California)]) |

Or | Or | ||

| − | + | <code> | |

| − | /Michael Brownlie/ (examples here: [https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/sigexamples_alt_text.pdf USPTO examples]) | + | /Michael Brownlie/</code> (examples here: [https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/sigexamples_alt_text.pdf USPTO examples]) |

If you wish to improve the level of assurance of the LoA 1 e-signature, it could be associated with an email address. For example, a business process could be designed that causes an email containing something unique and unpredictable to be sent to the chosen email address, and the signer could respond, including the text that was sent to them, with a signature following one of the formats above or something similar designed for the purpose. Such a process would show the intent to sign, accepting the conditions described, and the signature would be associated with the email address that the request was sent to, at least establishing that the e-signature was made by a person with control over the email address chosen. | If you wish to improve the level of assurance of the LoA 1 e-signature, it could be associated with an email address. For example, a business process could be designed that causes an email containing something unique and unpredictable to be sent to the chosen email address, and the signer could respond, including the text that was sent to them, with a signature following one of the formats above or something similar designed for the purpose. Such a process would show the intent to sign, accepting the conditions described, and the signature would be associated with the email address that the request was sent to, at least establishing that the e-signature was made by a person with control over the email address chosen. | ||

| Line 40: | Line 41: | ||

1. Emails | 1. Emails | ||

| − | [[File:Email_sign1.PNG]] | + | [[File:Email_sign1.PNG|center]] |

Above example is when sending the email. Note the use of /s/ to show intent to sign, though this may or may not be necessary and we are not implying that it is required in a signed email. | Above example is when sending the email. Note the use of /s/ to show intent to sign, though this may or may not be necessary and we are not implying that it is required in a signed email. | ||

| − | [[File: | + | [[File:Email_sign2b_annotated.png|center]] |

Above shows the Inbox of the recipient including a red icon to indicate digital signature. | Above shows the Inbox of the recipient including a red icon to indicate digital signature. | ||

| − | [[File:Email_sign3.PNG]] | + | [[File:Email_sign3.PNG|center]] |

Above is as the email will appear to the recipient when opened. | Above is as the email will appear to the recipient when opened. | ||

| Line 54: | Line 55: | ||

2. PDF documents | 2. PDF documents | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:Pdf_sign1.PNG|center]] |

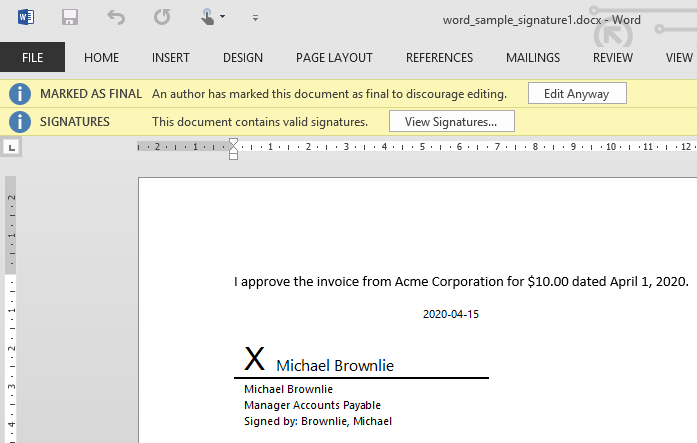

3. Microsoft Word documents | 3. Microsoft Word documents | ||

| − | [[File:Word_sign1.PNG]] | + | [[File:Word_sign1.PNG|center]] |

| − | We won’t go into detail here about how to set these up, as each technology choice could be a blog post on its own, but there are pros and cons to each of the choices that would have to be weighed by the business owner for the specific situation. The major takeaway is that each of these options can be used today by GC officials needing to sign documents as well as those verifying the signatures. Note that this latter step of verifying signatures is not always performed with physical, ink signatures, so the digital replacement using PKI has additional benefits. GC PKI credentials using soft tokens (epf files), which is the majority of such credentials within the GC, achieve an LoA 2. See [https://www.cse-cst.gc.ca/en/node/2454/html/28582 CSE ITSP.30.031 V3] for more details. GC PKI credentials using hard tokens and a rigorous identity-proofing process may achieve LoA 3 or even 4, if implemented in accordance with the level 4 requirements identified in the e-signature guidance document. In addition, GC PKI credentials come with strong LoA 2 identity-proofing baked in at a minimum (higher for many). | + | We won’t go into detail here about how to set these up, as each technology choice could be a blog post on its own, but there are pros and cons to each of the choices that would have to be weighed by the business owner for the specific situation. The major takeaway is that each of these options can be used today by GC officials needing to sign documents as well as those verifying the signatures. Note that this latter step of verifying signatures is not always performed with physical, ink signatures, so the digital replacement using PKI has additional benefits. GC PKI credentials using soft tokens (epf files), which is the majority of such credentials within the GC, achieve an LoA 2. See [https://www.cse-cst.gc.ca/en/node/2454/html/28582 CSE ITSP.30.031 V3] for more details. GC PKI credentials using hard tokens and a rigorous identity-proofing process may achieve LoA 3 or even 4, if implemented in accordance with the level 4 requirements identified in the [https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/online-security-privacy/government-canada-guidance-using-electronic-signatures.html e-signature guidance] document. In addition, GC PKI credentials come with strong LoA 2 identity-proofing baked in at a minimum (higher for many). |

=== Within the GC - Where the User is Associated with an Account === | === Within the GC - Where the User is Associated with an Account === | ||

If the user can log in to an account using an LoA 2 authentication, a straightforward option is to have the user log in and “click to sign”. There should be well-described consequences of the signing action so that the user is aware that she is performing a signing action. This option is already in wide use. An example from the GC is the e-signatures applied by both manager and employee as part of the Performance Management process. | If the user can log in to an account using an LoA 2 authentication, a straightforward option is to have the user log in and “click to sign”. There should be well-described consequences of the signing action so that the user is aware that she is performing a signing action. This option is already in wide use. An example from the GC is the e-signatures applied by both manager and employee as part of the Performance Management process. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Image:PSPM sign3.png|center]] |

=== Outside the GC - PKI-based E-Signature Solutions === | === Outside the GC - PKI-based E-Signature Solutions === | ||

| Line 75: | Line 76: | ||

As above, if the external user can log in to an account using an LoA 2 authentication, a simple approach is to have the user log in and “click to sign”. The CRA process for adding a child for child benefits within [https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/e-services/e-services-individuals/account-individuals.html My Account for Individuals] is an example of an e-signature where a user outside the GC is associated with an account. In these cases, the LoA of the e-signature is largely determined by the LoA of the authentication process used for logging in to the account. This is an example of LoA 2 because the credentials used to log in to those accounts are LoA 2. You can find more details on this in the e-signature guidance. | As above, if the external user can log in to an account using an LoA 2 authentication, a simple approach is to have the user log in and “click to sign”. The CRA process for adding a child for child benefits within [https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/e-services/e-services-individuals/account-individuals.html My Account for Individuals] is an example of an e-signature where a user outside the GC is associated with an account. In these cases, the LoA of the e-signature is largely determined by the LoA of the authentication process used for logging in to the account. This is an example of LoA 2 because the credentials used to log in to those accounts are LoA 2. You can find more details on this in the e-signature guidance. | ||

| − | [[File:CRA_signature_example.png]] | + | [[File:CRA_signature_example.png|center]] |

== Level of Assurance (LoA) 3: == | == Level of Assurance (LoA) 3: == | ||

| − | LoA 3 is appropriate when a high degree of confidence is required. It should be noted that LoA 4 is outside of the scope of this blog entry< | + | LoA 3 is appropriate when a high degree of confidence is required. It should be noted that LoA 4 is outside of the scope of this blog entry<ref><small>We expect the need for level 4 e-signatures to be rare (e.g. very high-value transactions) and the reader should consult the e-signature guidance document for additional information.</small></ref>. |

Two major technical options are available at LoA 3. | Two major technical options are available at LoA 3. | ||

| Line 98: | Line 99: | ||

== Secure Electronic Signature == | == Secure Electronic Signature == | ||

| − | As mentioned in the e-signature guidance, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and other federal legislation refer to the concept of a “Secure Electronic Signature” (SES). What constitutes an SES is governed by PIPEDA and the technology process described in the Secure Electronic Signature Regulations (SESR). Although PIPEDA mandates the use of SES in certain circumstances (e.g. federal legislative and regulatory requirements for witnessed signatures, statements declaring truth etc.), most of these do not apply unless a department has taken positive steps to have the provisions in question apply. Consult your DLSU for further information. At this point we would suggest that implementing Secure Electronic Signature is a challenging task that may not be fully achievable for some applications. | + | As mentioned in the [https://www.canada.ca/en/government/system/digital-government/online-security-privacy/government-canada-guidance-using-electronic-signatures.html e-signature guidance], the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and other federal legislation refer to the concept of a “Secure Electronic Signature” (SES). What constitutes an SES is governed by PIPEDA and the technology process described in the Secure Electronic Signature Regulations (SESR). Although PIPEDA mandates the use of SES in certain circumstances (e.g. federal legislative and regulatory requirements for witnessed signatures, statements declaring truth etc.), most of these do not apply unless a department has taken positive steps to have the provisions in question apply. Consult your DLSU for further information. At this point we would suggest that implementing Secure Electronic Signature is a challenging task that may not be fully achievable for some applications. |

At this time it is not clear if TBS can recognize external CAs in order to provide the certificates required to apply secure electronic signatures to documents such that they could be verified by members of the public. Even for internal use, not many users outside of RCMP and DND have access to certificates that have been enrolled with a suitable face to face procedure and have the private signing key stored on an approved FIPS 140-2 security token. | At this time it is not clear if TBS can recognize external CAs in order to provide the certificates required to apply secure electronic signatures to documents such that they could be verified by members of the public. Even for internal use, not many users outside of RCMP and DND have access to certificates that have been enrolled with a suitable face to face procedure and have the private signing key stored on an approved FIPS 140-2 security token. | ||

| Line 105: | Line 106: | ||

A short caution about using a digitized version (scan) of your wet signature from paper. Although PDF readers and editors often allow the user to insert a scan of her wet signature from paper, we do not consider this a good practice. Although it can give a signed electronic document a look that users are familiar with, we would argue that there is no real assurance or security achieved by inserting such a scan beyond what is achieved by typing a name as signature (e.g. /s/ Michael Brownlie). In addition, there is a risk in distributing an authentic copy of one’s wet signature around cyber space that a malicious actor could grab a copy and use it in concert with technology such as colour photocopiers to create facsimiles of one’s wet signature in the paper world (e.g. on formal contracts or other documents rendered on paper). In short, there is little gain in assurance while at the same time there is a potential risk introduced unnecessarily into the world of physical signatures. | A short caution about using a digitized version (scan) of your wet signature from paper. Although PDF readers and editors often allow the user to insert a scan of her wet signature from paper, we do not consider this a good practice. Although it can give a signed electronic document a look that users are familiar with, we would argue that there is no real assurance or security achieved by inserting such a scan beyond what is achieved by typing a name as signature (e.g. /s/ Michael Brownlie). In addition, there is a risk in distributing an authentic copy of one’s wet signature around cyber space that a malicious actor could grab a copy and use it in concert with technology such as colour photocopiers to create facsimiles of one’s wet signature in the paper world (e.g. on formal contracts or other documents rendered on paper). In short, there is little gain in assurance while at the same time there is a potential risk introduced unnecessarily into the world of physical signatures. | ||

| − | == Beyond the Actual Signature< | + | == Beyond the Actual Signature<ref><small>As a reminder, security always needs to be taken into consideration, especially when dealing with parties external to the Government of Canada who may not have secure means of communication or storage. As mentioned in the e-signature guidance, confidentiality is not addressed by electronic signatures. If using an unsecure means of communication such as email, MS Word or PDF documents with the public, departments should be mindful of relevant, applicable policies. In particular, Appendix B of the Directive on Security Management states that encryption and network safeguards must be used to protect the confidentiality of sensitive data transmitted across public networks, wireless networks or any other network where the data may be at risk of unauthorized access. (B.2.3.6.3). Although sensitive information is not defined in the Directive, the Policy on Government Security defines “sensitive information” as “information or asset that if compromised would reasonably be expected to cause an injury. This includes all information that falls within the exemption or exclusion criteria under the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. This also includes controlled goods as well as other information and assets that have regulatory or statutory prohibitions and controls.” As such communication using public email, may not be appropriate in many given circumstances due to security risks.</small></ref> == |

A further consideration in moving from physical signatures to electronic signatures is the assurance level of the physical signature that is being replaced. In talking with practitioners who are implementing e-signatures, we often hear about weaknesses in the existing physical signature process while the proposed replacement with an e-signature is being scrutinized rigorously to achieve a high level of assurance. As an example, many processes involving physical signatures on forms do not implement a check of that signature against a pre-established signature card (or perform any other validation of the signature). We would suggest that such a physical signature process is at best a level of assurance 1. Now with those processes there may be other compensating controls in place that must be considered when moving to an e-signature, but the robustness of the signature itself is probably not high. These additional controls are important. An example might be a PDF form that is sent to a user for printing, ink signing, scanning, and emailing back (a partially digital process that still requires a physical signature). The fact that the user was able to receive the email on a known email address may be considered an additional control on the process and this could be replicated into the replacement electronic signature process. | A further consideration in moving from physical signatures to electronic signatures is the assurance level of the physical signature that is being replaced. In talking with practitioners who are implementing e-signatures, we often hear about weaknesses in the existing physical signature process while the proposed replacement with an e-signature is being scrutinized rigorously to achieve a high level of assurance. As an example, many processes involving physical signatures on forms do not implement a check of that signature against a pre-established signature card (or perform any other validation of the signature). We would suggest that such a physical signature process is at best a level of assurance 1. Now with those processes there may be other compensating controls in place that must be considered when moving to an e-signature, but the robustness of the signature itself is probably not high. These additional controls are important. An example might be a PDF form that is sent to a user for printing, ink signing, scanning, and emailing back (a partially digital process that still requires a physical signature). The fact that the user was able to receive the email on a known email address may be considered an additional control on the process and this could be replicated into the replacement electronic signature process. | ||

| Line 111: | Line 112: | ||

The purpose of this blog has been to present some possible technical approaches for e-signatures that are already available for use. We are interested in having a dialog with practitioners and hope that you will contact us or comment here on the blog in order to expand the dialog and speed up digital government initiatives. | The purpose of this blog has been to present some possible technical approaches for e-signatures that are already available for use. We are interested in having a dialog with practitioners and hope that you will contact us or comment here on the blog in order to expand the dialog and speed up digital government initiatives. | ||

| − | + | ==Questions and Contact Information== | |

| − | + | For questions and other enquiries please email [mailto:ZZTBSCYBERS@tbs-sct.gc.ca TBS-Cyber Security].<br> | |

| − | + | To join a discussion from within the GC, see [https://gccollab.ca/discussion/view/4619705/enblog-on-e-signature-options-available-today-to-gc-departmentsfr GCcollab discussion]. | |

| − | == | + | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <br> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | <!-- FRENCH --> | ||

| + | @fr|__NOTOC__ | ||

= Options de signature électronique disponibles pour utilisation immédiate au sein du gouvernement du Canada (GC) = | = Options de signature électronique disponibles pour utilisation immédiate au sein du gouvernement du Canada (GC) = | ||

| Line 141: | Line 138: | ||

Les Règles locales civiles de la Cour de district des États-Unis, District du nord de la Californie | Les Règles locales civiles de la Cour de district des États-Unis, District du nord de la Californie | ||

| − | /s/ Michael | + | <pre> |

| + | /s/ Michael Brownlie</pre> (décrit ici : [https://www.cand.uscourts.gov/cases-e-filing/cm-ecf/preparing-my-filing/signatures-on-e-filed-documents/ Cour de district des États-Unis, District du nord de la Californie]) | ||

Ou | Ou | ||

| Line 147: | Line 145: | ||

Le « ''Code of Federal Regulations'' (CFR)» 37 1.4 - ''Code américain des règlements fédéraux'' qui inclut des exigences de signature pour la correspondance avec l’Office américain des marques et brevets (USPTO) | Le « ''Code of Federal Regulations'' (CFR)» 37 1.4 - ''Code américain des règlements fédéraux'' qui inclut des exigences de signature pour la correspondance avec l’Office américain des marques et brevets (USPTO) | ||

| − | /Michael Brownlie/ (exemples ici : exemples du USPTO) | + | <pre> |

| + | /Michael Brownlie/</pre> (exemples ici : [https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/sigexamples_alt_text.pdf exemples du USPTO]) | ||

Si vous souhaitez améliorer le degré d’assurance de la signature électronique DA 1, cette dernière pourrait être associée à une adresse de courriel. Par exemple, un processus opérationnel pourrait être conçu de sorte qu’un courriel au contenu unique et imprévisible soit envoyé à l’adresse de courriel choisie, à partir d’où le signataire peut y répondre, en incluant le texte qui lui a été envoyé, avec une signature suivant l’un des formats ci-dessus ou quelque chose de semblable ayant été conçu à cette fin. Un tel processus montrerait l’intention de signer, en acceptant les conditions décrites, et la signature serait associée à l’adresse de courriel à laquelle la demande a été envoyée, établissant au moins que la signature électronique a été faite par une personne qui contrôle l’adresse de courriel choisie. | Si vous souhaitez améliorer le degré d’assurance de la signature électronique DA 1, cette dernière pourrait être associée à une adresse de courriel. Par exemple, un processus opérationnel pourrait être conçu de sorte qu’un courriel au contenu unique et imprévisible soit envoyé à l’adresse de courriel choisie, à partir d’où le signataire peut y répondre, en incluant le texte qui lui a été envoyé, avec une signature suivant l’un des formats ci-dessus ou quelque chose de semblable ayant été conçu à cette fin. Un tel processus montrerait l’intention de signer, en acceptant les conditions décrites, et la signature serait associée à l’adresse de courriel à laquelle la demande a été envoyée, établissant au moins que la signature électronique a été faite par une personne qui contrôle l’adresse de courriel choisie. | ||

| Line 169: | Line 168: | ||

3) Documents Microsoft Word | 3) Documents Microsoft Word | ||

| − | Nous n’entrerons pas dans les détails quant à la façon de les mettre en place, car chaque choix technologique pourrait être le sujet d’un billet de blogue en soi, mais il y a certains avantages et inconvénients à chacun des choix qui devraient être soupesés par le responsable opérationnel, en fonction de la situation particulière. Le principal point à retenir est que chacune de ces options peut être utilisée aujourd’hui par les représentants du GC qui doivent signer des documents, ainsi que par ceux qui vérifient les signatures. Veuillez prendre note que cette dernière étape de vérification des signatures n’est pas toujours effectuée avec des signatures physiques à l’encre, de sorte que le remplacement numérique à l’aide de l’ICP présente des avantages supplémentaires. Les justificatifs d’identité de l’ICP du GC utilisant des jetons logiciels (fichiers epf), qui représentent la majorité de ces justificatifs d’identité au sein du GC, obtiennent un DA 2. Voir le guide ITSP.30.031 V3 du CST pour obtenir de plus amples détails. Les justificatifs d’identité de l’ICP du GC utilisant des jetons d’authentification et un processus rigoureux de vérification de l’identité peuvent atteindre le DA 3 ou même DA 4, s’ils sont mis en œuvre conformément aux exigences de niveau 4 définies dans le document d’Orientation du gouvernement du Canada sur les signatures électroniques. De plus, les justificatifs d’identité de l’ICP du GC sont assortis d’une solide résistance à l’identité de DA 2 intégrée au minimum (plus élevée pour beaucoup). | + | Nous n’entrerons pas dans les détails quant à la façon de les mettre en place, car chaque choix technologique pourrait être le sujet d’un billet de blogue en soi, mais il y a certains avantages et inconvénients à chacun des choix qui devraient être soupesés par le responsable opérationnel, en fonction de la situation particulière. Le principal point à retenir est que chacune de ces options peut être utilisée aujourd’hui par les représentants du GC qui doivent signer des documents, ainsi que par ceux qui vérifient les signatures. Veuillez prendre note que cette dernière étape de vérification des signatures n’est pas toujours effectuée avec des signatures physiques à l’encre, de sorte que le remplacement numérique à l’aide de l’ICP présente des avantages supplémentaires. Les justificatifs d’identité de l’ICP du GC utilisant des jetons logiciels (fichiers epf), qui représentent la majorité de ces justificatifs d’identité au sein du GC, obtiennent un DA 2. Voir le guide [https://www.cse-cst.gc.ca/fr/node/2454/html/28582 ITSP.30.031 V3 du CST] pour obtenir de plus amples détails. Les justificatifs d’identité de l’ICP du GC utilisant des jetons d’authentification et un processus rigoureux de vérification de l’identité peuvent atteindre le DA 3 ou même DA 4, s’ils sont mis en œuvre conformément aux exigences de niveau 4 définies dans le document d’Orientation du gouvernement du Canada sur les signatures électroniques. De plus, les justificatifs d’identité de l’ICP du GC sont assortis d’une solide résistance à l’identité de DA 2 intégrée au minimum (plus élevée pour beaucoup). |

=== Au sein du GC – Lorsque l’utilisateur est associé à un compte === | === Au sein du GC – Lorsque l’utilisateur est associé à un compte === | ||

| Line 180: | Line 179: | ||

=== À l’extérieur du GC – Lorsque l’utilisateur est associé à un compte === | === À l’extérieur du GC – Lorsque l’utilisateur est associé à un compte === | ||

| − | Comme ci-dessus, si l’utilisateur externe peut accéder à un compte à l’aide d’une authentification de DA 2, une approche simple consiste à demander à l’utilisateur d’ouvrir une séance et de « Cliquer pour signer ». Le processus de l’ARC pour modifier les détails du dépôt direct pour les remboursements d’impôt sur le revenu dans Mon dossier pour les particuliers est un exemple de comptes électroniques associés au public. Dans ces cas, les DA sont en grande partie déterminés par les DA du processus d’authentification utilisé pour accéder au compte. Voici un exemple de DA 2 parce que les justificatifs d’identité utilisés pour accéder à ces comptes sont de DA 2. Vous trouverez de plus amples détails à ce sujet dans le document d’Orientation du gouvernement du Canada sur les signatures électroniques. | + | Comme ci-dessus, si l’utilisateur externe peut accéder à un compte à l’aide d’une authentification de DA 2, une approche simple consiste à demander à l’utilisateur d’ouvrir une séance et de « Cliquer pour signer ». Le processus de l’ARC pour modifier les détails du dépôt direct pour les remboursements d’impôt sur le revenu dans [https://www.canada.ca/fr/agence-revenu/services/services-electroniques/services-electroniques-particuliers/dossier-particuliers.html Mon dossier pour les particuliers] est un exemple de comptes électroniques associés au public. Dans ces cas, les DA sont en grande partie déterminés par les DA du processus d’authentification utilisé pour accéder au compte. Voici un exemple de DA 2 parce que les justificatifs d’identité utilisés pour accéder à ces comptes sont de DA 2. Vous trouverez de plus amples détails à ce sujet dans le document d’Orientation du gouvernement du Canada sur les signatures électroniques. |

== Degré d’assurance (DA) 3 : == | == Degré d’assurance (DA) 3 : == | ||

| − | Le DA 3 est approprié lorsqu’un degré élevé de confiance est requis. Il convient de prendre note que le DA 4 ne fait pas partie de la portée de ce billet de blogue. | + | Le DA 3 est approprié lorsqu’un degré élevé de confiance est requis. Il convient de prendre note que le DA 4 ne fait pas partie de la portée de ce billet de blogue<ref><small>Nous nous attendons à ce que le besoin de signatures électroniques de niveau 4 soit rare (p. ex., transactions de très grande valeur), et le lecteur devrait consulter le document d’Orientation du gouvernement du Canada sur les signatures électroniques pour obtenir de plus amples renseignements.</small></ref>. |

Deux grandes options techniques sont disponibles au DA 3. | Deux grandes options techniques sont disponibles au DA 3. | ||

| Line 192: | Line 191: | ||

Il y a un certain nombre de détails techniques pour une autre discussion, mais soyez prêts à examiner attentivement la façon dont vous utiliseriez cette technologie. Par exemple, il faut tenir compte de choses comme la validation à long terme des documents. | Il y a un certain nombre de détails techniques pour une autre discussion, mais soyez prêts à examiner attentivement la façon dont vous utiliseriez cette technologie. Par exemple, il faut tenir compte de choses comme la validation à long terme des documents. | ||

| − | Les membres AATL comptent une AC canadienne et une autre AC que le GC utilise depuis de nombreuses années comme fournisseur d’ICP. | + | Les [https://helpx.adobe.com/ca_fr/acrobat/kb/approved-trust-list1.html membres AATL] comptent une AC canadienne et une autre AC que le GC utilise depuis de nombreuses années comme fournisseur d’ICP. |

À bien des égards, cette technologie est proche de ce qui était envisagé à l’origine pour la signature électronique sécurisée du Canada (voir ci-dessous), bien que nous soyons encore en train d’examiner comment le SCT pourrait reconnaître les AC externes à cette fin, ou s’il devait le faire. | À bien des égards, cette technologie est proche de ce qui était envisagé à l’origine pour la signature électronique sécurisée du Canada (voir ci-dessous), bien que nous soyons encore en train d’examiner comment le SCT pourrait reconnaître les AC externes à cette fin, ou s’il devait le faire. | ||

| Line 210: | Line 209: | ||

Voici une courte mise en garde contre l’utilisation d’une version numérisée de votre signature manuscrite sur papier. Bien que les lecteurs et éditeurs de documents PDF permettent souvent à leur utilisateur d’insérer une copie numérisée de sa signature manuscrite sur papier, nous ne considérons pas qu’il s’agit d’une bonne pratique. Bien qu’une telle pratique puisse donner à un document électronique signé un aspect familier aux utilisateurs, nous sommes d’avis qu’il n’y a pas d’assurance ou de garantie sécuritaire réelle obtenue en insérant une telle signature numérisée au-delà de ce qui est obtenu en tapant un nom comme signature (p. ex., /s/ Michael Brownlie). De plus, la diffusion dans le cyberespace de la copie authentique d’une signature manuscrite n’échappe pas au risque qu’une personne malveillante accapare cette copie et l’utilise de concert avec une technologie, comme la photocopie couleur, pour créer d’autres copies de cette même signature sur papier (p. ex., sur des contrats officiels ou d’autres documents papier). Bref, cette méthode accorde peu de gains d’assurance, tout en posant un risque possible qu’il est possible d’éviter en matière de signatures réelles. | Voici une courte mise en garde contre l’utilisation d’une version numérisée de votre signature manuscrite sur papier. Bien que les lecteurs et éditeurs de documents PDF permettent souvent à leur utilisateur d’insérer une copie numérisée de sa signature manuscrite sur papier, nous ne considérons pas qu’il s’agit d’une bonne pratique. Bien qu’une telle pratique puisse donner à un document électronique signé un aspect familier aux utilisateurs, nous sommes d’avis qu’il n’y a pas d’assurance ou de garantie sécuritaire réelle obtenue en insérant une telle signature numérisée au-delà de ce qui est obtenu en tapant un nom comme signature (p. ex., /s/ Michael Brownlie). De plus, la diffusion dans le cyberespace de la copie authentique d’une signature manuscrite n’échappe pas au risque qu’une personne malveillante accapare cette copie et l’utilise de concert avec une technologie, comme la photocopie couleur, pour créer d’autres copies de cette même signature sur papier (p. ex., sur des contrats officiels ou d’autres documents papier). Bref, cette méthode accorde peu de gains d’assurance, tout en posant un risque possible qu’il est possible d’éviter en matière de signatures réelles. | ||

| − | == Au-delà de la signature comme telle == | + | == Au-delà de la signature comme telle<ref><small>À titre de rappel, on doit toujours prendre la sécurité en considération, surtout lorsqu’on traite avec des parties externes au gouvernement du Canada qui n’ont peut-être pas de moyens de communication ou d’entreposage sécuritaires. Comme il est mentionné dans le document d’orientation sur la signature électronique, les signatures électroniques n’assurent pas toujours la confidentialité. S’ils communiquent par moyen non sécurisé comme le courriel, Microsoft Word ou des documents PDF avec le public, les ministères doivent tenir compte des politiques pertinentes et applicables. En particulier, l’annexe B de la Directive sur la gestion de la sécurité stipule que l’on doit avoir recours au chiffrement et à des mesures de protection des réseaux pour assurer la confidentialité des données sensibles transmises sur les réseaux publics, les réseaux sans fil ou tout autre réseau où il y a risque d’accès non autorisé aux données. (B.2.3.6.3). Bien que la Directive ne contienne aucune définition de ce qui constitue des renseignements sensibles, la Politique sur la sécurité du gouvernement définit les « renseignements sensibles » comme des « informations ou biens qui devraient raisonnablement causer un préjudice s’ils sont compromis. Cela comprend tous les renseignements qui répondent aux critères d’exemption ou d’exclusion en vertu de la Loi sur l’accès à l’information et de la Loi sur la protection des renseignements personnels. Y sont également compris les marchandises contrôlées et d’autres renseignements et biens qui font l’objet d’interdictions et de mesures réglementaires ou légales ». En tant que telle, la communication par courriel public peut ne pas être appropriée dans de nombreuses circonstances en raison des risques pour la sécurité.</small></ref> == |

Un autre facteur à considérer pour passer des signatures physiques aux signatures électroniques est le degré d’assurance de la signature physique qui est remplacée. En discutant avec des praticiens qui mettent en œuvre les signatures électroniques, nous entendons souvent parler de faiblesses dans le processus de signature physique actuel, alors que le remplacement proposé par une signature électronique est examiné rigoureusement pour atteindre un degré d’assurance élevé. Par exemple, de nombreux processus comportant des signatures physiques sur les formulaires ne permettent pas de vérifier cette signature par rapport à une fiche-signature préétablie (ou d’effectuer toute autre validation de la signature). À notre avis, un tel processus de signature physique offre au mieux un degré d’assurance 1. Maintenant, avec ces processus, il y a peut-être d’autres mesures compensatoires en place dont on doit tenir compte lorsqu’on passe à une signature électronique, mais la robustesse de la signature comme telle n’est probablement pas élevée. Ces contrôles supplémentaires sont importants. Par exemple, un formulaire PDF peut être envoyé à un utilisateur pour qu’il l’imprime, le signe à l’encre, le numérise et le renvoie par courriel (un processus partiellement numérique qui exige toujours une signature physique). Le fait que l’utilisateur ait pu recevoir le courriel à une adresse de courriel connue peut être considéré comme un contrôle supplémentaire du processus et pourrait être reproduit dans le processus de signature électronique de remplacement. | Un autre facteur à considérer pour passer des signatures physiques aux signatures électroniques est le degré d’assurance de la signature physique qui est remplacée. En discutant avec des praticiens qui mettent en œuvre les signatures électroniques, nous entendons souvent parler de faiblesses dans le processus de signature physique actuel, alors que le remplacement proposé par une signature électronique est examiné rigoureusement pour atteindre un degré d’assurance élevé. Par exemple, de nombreux processus comportant des signatures physiques sur les formulaires ne permettent pas de vérifier cette signature par rapport à une fiche-signature préétablie (ou d’effectuer toute autre validation de la signature). À notre avis, un tel processus de signature physique offre au mieux un degré d’assurance 1. Maintenant, avec ces processus, il y a peut-être d’autres mesures compensatoires en place dont on doit tenir compte lorsqu’on passe à une signature électronique, mais la robustesse de la signature comme telle n’est probablement pas élevée. Ces contrôles supplémentaires sont importants. Par exemple, un formulaire PDF peut être envoyé à un utilisateur pour qu’il l’imprime, le signe à l’encre, le numérise et le renvoie par courriel (un processus partiellement numérique qui exige toujours une signature physique). Le fait que l’utilisateur ait pu recevoir le courriel à une adresse de courriel connue peut être considéré comme un contrôle supplémentaire du processus et pourrait être reproduit dans le processus de signature électronique de remplacement. | ||

| Line 216: | Line 215: | ||

Ce blogue avait pour but de présenter certaines approches techniques possibles pour les signatures électroniques qui sont déjà disponibles. Nous souhaitons avoir un dialogue avec les praticiens et nous espérons que vous communiquerez avec nous ou formulerez des commentaires ici sur le blogue afin d’élargir la discussion et d’accélérer les initiatives du gouvernement numérique. | Ce blogue avait pour but de présenter certaines approches techniques possibles pour les signatures électroniques qui sont déjà disponibles. Nous souhaitons avoir un dialogue avec les praticiens et nous espérons que vous communiquerez avec nous ou formulerez des commentaires ici sur le blogue afin d’élargir la discussion et d’accélérer les initiatives du gouvernement numérique. | ||

| + | ==Questions et Informations de Contact== | ||

| + | Pour des questions et des autres demandes de renseignements, veuillez envoyer un courriel à [mailto:ZZTBSCYBERS@tbs-sct.gc.ca SCT-Cyber Securité].<br> | ||

| + | Pour participer à une discussion au sein gu GC, suivre [https://gccollab.ca/discussion/view/4619705/enblog-on-e-signature-options-available-today-to-gc-departmentsfr discussion GCcollab]. | ||

| + | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</multilang> | </multilang> | ||

| + | {{DEFAULTSORT:E-Signatures in the GC/E-SIgnature Options 2020-04}} | ||

Latest revision as of 11:21, 8 July 2020

Electronic Signature Options Available for Immediate Use Within the Government of Canada (GC)

The purpose of this blog post is to suggest some e-signature options that are available to federal government officials wishing to implement immediate alternatives to wet signatures in light of the limitations arising out of the current COVID-19 situation. The social distancing measures currently in place to slow the spread of COVID-19 and the need for rapid assistance to Canadians may require the implementation of immediate digital government solutions, to assist in making government more efficient in delivering needed services to Canadians. These solutions may be necessary for internal as well as external-facing government transactions. For example, because of current social-distancing measures, government officials may not have access to printers and limited access to certain government networks, making it difficult to authorize internal transactions that normally would require forms and wet signatures. Similarly, departments might be considering alternative means for communicating decisions or authorizations to members of the public (e.g. electronic issuance of decisions, permits etc.). Consideration might also be given to allow members of the public to submit certain documents electronically. The following informal guidance is meant to assist government officials in determining what operational e-signature solutions might be appropriate in the given circumstances. In addition, we hope it will generate discussion and additional options and ideas will come to light.

This guidance should be read in conjunction with the Government of Canada E-Signature Guidance 2019 released by TBS in July 2019. The Guide can be used to inform the development of streamlined digital services that previously relied upon handwritten signatures on paper. A PDF form that needs to be printed, signed, scanned, and emailed back is not a true digital process.

The Government of Canada E-Signature Guidance 2019 provides a four level of assurance model of e-signatures that government officials can use to meet their requirements. These levels of assurance are based on those found in the Guideline on Defining Authentication Requirements If your process requires or would benefit from signatures, please read and apply the guidance to your process.

This document includes the views of the Cyber Security group at TBS, and should not be interpreted as official government policy. We in TBS Cyber Security are available to assist and offer guidance by sharing ideas and knowledge developed over the past couple of years of development of the e-signature guidance in discussions and review with practitioners across the GC. It is important to note that your Departmental Legal Services Unit (DLSU) should also be consulted to ensure compliance with any legal requirements.

To that end, here are some e-signature options that we believe could be deployed rapidly using existing technologies available within the GC.

Level of Assurance (LoA) 1:

LoA 1 is appropriate where a low degree of confidence is required.

At LoA 1, a user can type her name at the bottom of an email or doc. ument to indicate acceptance of conditions described above in the document or authorization for some purpose. We would recommend that the typed name be marked specially and that the context provided by the wording preceding the signature help make the purpose of the signature clear. Some jurisdictions have adopted a unique format to the typed signature such as

/s/ Michael Brownlie (described here: United States District Court (Northern California))

Or

/Michael Brownlie/ (examples here: USPTO examples)

If you wish to improve the level of assurance of the LoA 1 e-signature, it could be associated with an email address. For example, a business process could be designed that causes an email containing something unique and unpredictable to be sent to the chosen email address, and the signer could respond, including the text that was sent to them, with a signature following one of the formats above or something similar designed for the purpose. Such a process would show the intent to sign, accepting the conditions described, and the signature would be associated with the email address that the request was sent to, at least establishing that the e-signature was made by a person with control over the email address chosen.

Building on the idea of associating an e-signature with an email address, an approach already in relatively common use is to send an email to the address associated with a person whose approval is required. The email contains a link unique to the signature being requested that, when clicked on, takes the user to a web page where she is presented with the request details and a click to sign button. When the user clicks, all the necessary details are stored as a record of the signature and what was signed (including the unique link that was only sent to the signer).

The above LoA 1 approaches apply both inside government processes or with the Canadian Public.

Level of Assurance (LoA) 2:

LoA 2 is appropriate where reasonable (some) confidence is required.

There are a number of solid options available for LoA 2 signatures both with internal GC parties and with the Canadian public.

Within the GC - PKI-based E-Signature Solutions

PKI credentials (e.g. from the Internal Credential Management Service - myKEY, RCMP, DND, or CRA) can be used to sign three different types of documents:

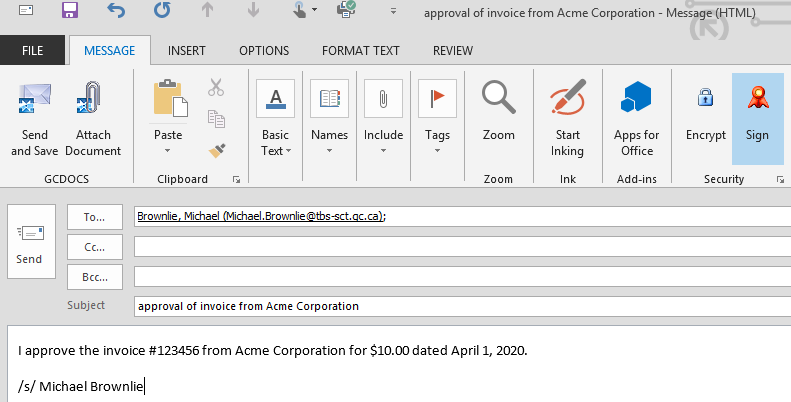

1. Emails

Above example is when sending the email. Note the use of /s/ to show intent to sign, though this may or may not be necessary and we are not implying that it is required in a signed email.

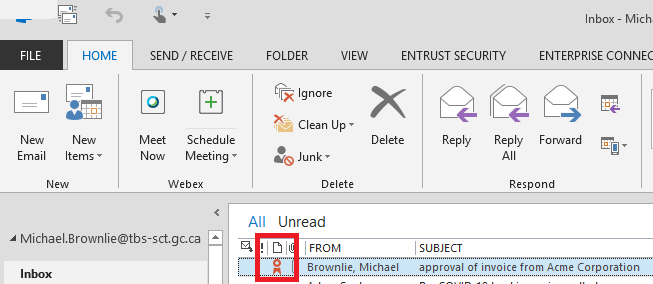

Above shows the Inbox of the recipient including a red icon to indicate digital signature.

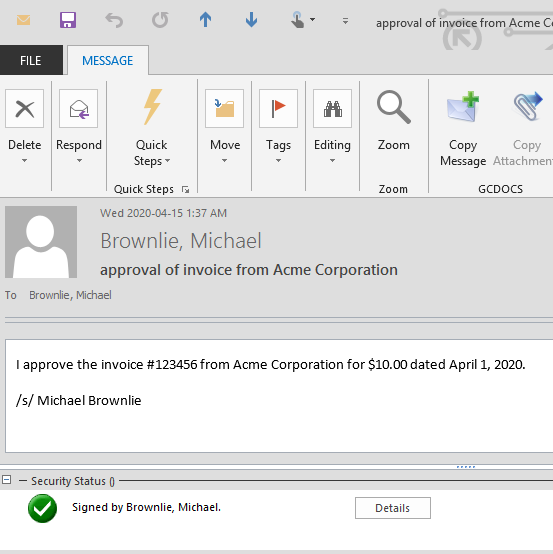

Above is as the email will appear to the recipient when opened.

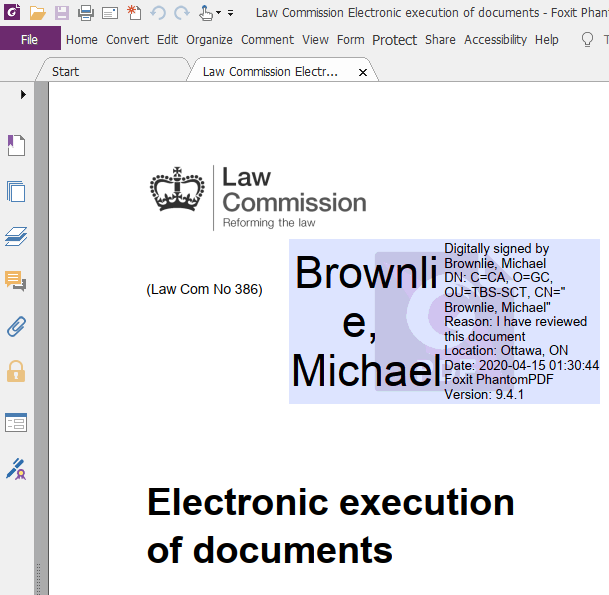

2. PDF documents

3. Microsoft Word documents

We won’t go into detail here about how to set these up, as each technology choice could be a blog post on its own, but there are pros and cons to each of the choices that would have to be weighed by the business owner for the specific situation. The major takeaway is that each of these options can be used today by GC officials needing to sign documents as well as those verifying the signatures. Note that this latter step of verifying signatures is not always performed with physical, ink signatures, so the digital replacement using PKI has additional benefits. GC PKI credentials using soft tokens (epf files), which is the majority of such credentials within the GC, achieve an LoA 2. See CSE ITSP.30.031 V3 for more details. GC PKI credentials using hard tokens and a rigorous identity-proofing process may achieve LoA 3 or even 4, if implemented in accordance with the level 4 requirements identified in the e-signature guidance document. In addition, GC PKI credentials come with strong LoA 2 identity-proofing baked in at a minimum (higher for many).

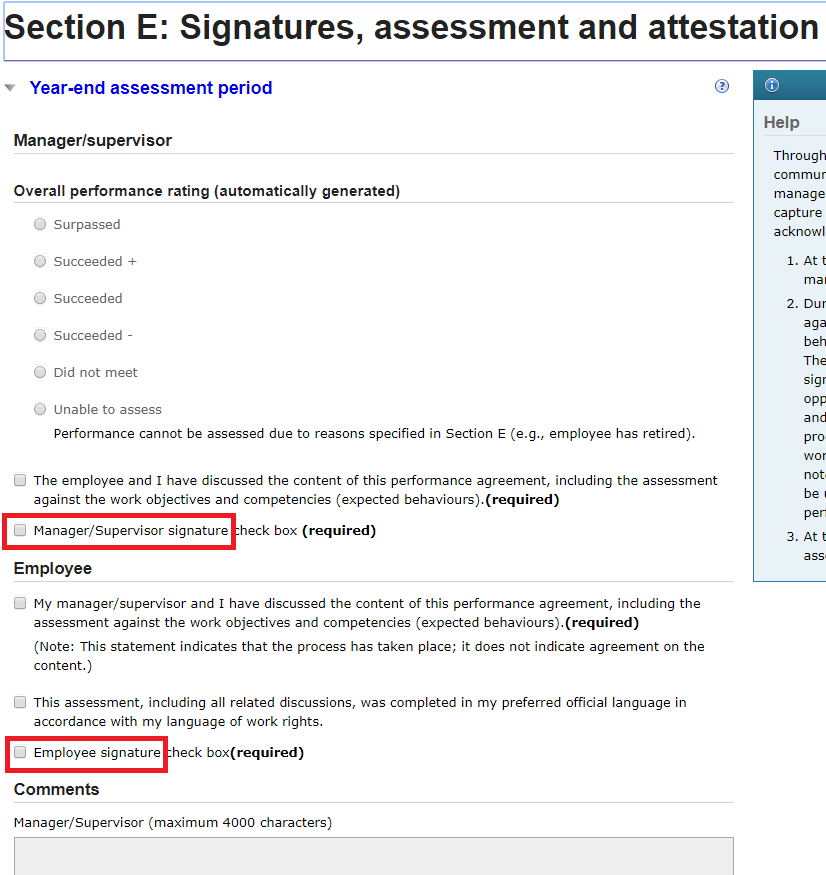

Within the GC - Where the User is Associated with an Account

If the user can log in to an account using an LoA 2 authentication, a straightforward option is to have the user log in and “click to sign”. There should be well-described consequences of the signing action so that the user is aware that she is performing a signing action. This option is already in wide use. An example from the GC is the e-signatures applied by both manager and employee as part of the Performance Management process.

Outside the GC - PKI-based E-Signature Solutions

Note that in special cases, GC PKI-based signatures could be applied to the three types of documents mentioned above and sent to a user outside of government who could then apply a special, manual process to verify the signature, but this approach would absolutely not scale to the general Canadian public.

Users outside the GC rarely have access to PKI credentials that could be used to digitally sign, therefore it would be an unusual situation where a process for external parties to perform e-signatures could be designed around PKI-based solutions. In one-off situations where a user outside the GC does have a PKI credential, a PKI-based signature with a manual process to verify the signature on the GC side could be an option.

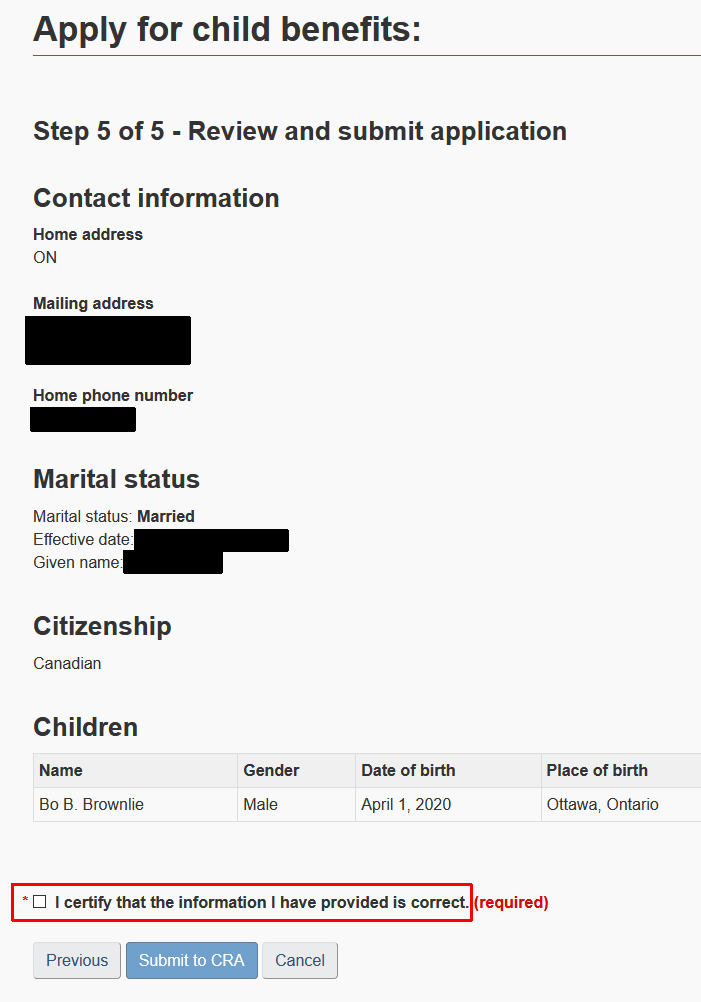

Outside the GC - Where the User is Associated with an Account

As above, if the external user can log in to an account using an LoA 2 authentication, a simple approach is to have the user log in and “click to sign”. The CRA process for adding a child for child benefits within My Account for Individuals is an example of an e-signature where a user outside the GC is associated with an account. In these cases, the LoA of the e-signature is largely determined by the LoA of the authentication process used for logging in to the account. This is an example of LoA 2 because the credentials used to log in to those accounts are LoA 2. You can find more details on this in the e-signature guidance.

Level of Assurance (LoA) 3:

LoA 3 is appropriate when a high degree of confidence is required. It should be noted that LoA 4 is outside of the scope of this blog entry[1].

Two major technical options are available at LoA 3.

Digitally-signed PDF documents using PKI-based AATL certificates

The Portable Document Format (PDF) standard includes the ability to digitally sign electronic documents using PKI technology. In addition, Adobe has created a program called Adobe Approved Trust List (AATL) that allows any user with a certificate from an approved certification authority (CA) to digitally sign documents that are trusted by any user around the world when opened using a PDF viewer from Adobe and other vendors. The AATL ensures that signers with certificates are identity-proofed and that the private key used for the digital signature is kept secure on a hardware token. In addition to providing proof of the identity of the signer of the document, this technology also ensures that the document has not been tampered with since it was signed. Since the majority of people do not have the certificates needed to create these signatures, this approach is suited to a use case where you need (a small number of people) to certify authentic documents that you wish to send to be viewed potentially by a large number of people.

There are a number of technical details for another discussion, but be prepared to do a careful investigation into how you would use this technology. For example, things such as long-term validation of documents need to be considered.

On the AATL Member List there is one Canadian CA and another that the GC has used for many years as a PKI vendor.

This technology is in many ways close to what was originally envisioned for Canada’s Secure Electronic Signature (see below), though at this time we are still investigating how or if TBS could recognize external CAs for this purpose.

Where the user is associated with an account

As above in the LoA 2 section, a user who has logged in to an account at LoA 3, which means using multi-factor authentication, can “click to sign” to approve, accept, or otherwise apply her signature.

Use of an External Service

There are a number of external electronic signature services that can be procured and integrated with your business process. Such services are becoming more common and can be seen in use, for example, in real estate transactions across Canada. Options are available certainly from LoA 1 to 3. Thus these options are available as rapidly as your internal assessment and procurement processes allow.

Secure Electronic Signature

As mentioned in the e-signature guidance, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) and other federal legislation refer to the concept of a “Secure Electronic Signature” (SES). What constitutes an SES is governed by PIPEDA and the technology process described in the Secure Electronic Signature Regulations (SESR). Although PIPEDA mandates the use of SES in certain circumstances (e.g. federal legislative and regulatory requirements for witnessed signatures, statements declaring truth etc.), most of these do not apply unless a department has taken positive steps to have the provisions in question apply. Consult your DLSU for further information. At this point we would suggest that implementing Secure Electronic Signature is a challenging task that may not be fully achievable for some applications.

At this time it is not clear if TBS can recognize external CAs in order to provide the certificates required to apply secure electronic signatures to documents such that they could be verified by members of the public. Even for internal use, not many users outside of RCMP and DND have access to certificates that have been enrolled with a suitable face to face procedure and have the private signing key stored on an approved FIPS 140-2 security token.

Scanned Versions of Wet Signatures

A short caution about using a digitized version (scan) of your wet signature from paper. Although PDF readers and editors often allow the user to insert a scan of her wet signature from paper, we do not consider this a good practice. Although it can give a signed electronic document a look that users are familiar with, we would argue that there is no real assurance or security achieved by inserting such a scan beyond what is achieved by typing a name as signature (e.g. /s/ Michael Brownlie). In addition, there is a risk in distributing an authentic copy of one’s wet signature around cyber space that a malicious actor could grab a copy and use it in concert with technology such as colour photocopiers to create facsimiles of one’s wet signature in the paper world (e.g. on formal contracts or other documents rendered on paper). In short, there is little gain in assurance while at the same time there is a potential risk introduced unnecessarily into the world of physical signatures.

Beyond the Actual Signature[2]

A further consideration in moving from physical signatures to electronic signatures is the assurance level of the physical signature that is being replaced. In talking with practitioners who are implementing e-signatures, we often hear about weaknesses in the existing physical signature process while the proposed replacement with an e-signature is being scrutinized rigorously to achieve a high level of assurance. As an example, many processes involving physical signatures on forms do not implement a check of that signature against a pre-established signature card (or perform any other validation of the signature). We would suggest that such a physical signature process is at best a level of assurance 1. Now with those processes there may be other compensating controls in place that must be considered when moving to an e-signature, but the robustness of the signature itself is probably not high. These additional controls are important. An example might be a PDF form that is sent to a user for printing, ink signing, scanning, and emailing back (a partially digital process that still requires a physical signature). The fact that the user was able to receive the email on a known email address may be considered an additional control on the process and this could be replicated into the replacement electronic signature process.

Much of what is important with signatures is ensuring that the process captures an individual’s intent to sign and additionally the integrity of the information submitted. Above we have offered some technical options for the electronic signature portion of the process that are already available for use by the Government of Canada to move forward more rapidly with digital government processes. As well as the technical option chosen for an e-signature, you will need to consider the original purpose and intention of the paper-based requirements and determine what equivalents you need as part of any e-transaction based on the risks that arise.

The purpose of this blog has been to present some possible technical approaches for e-signatures that are already available for use. We are interested in having a dialog with practitioners and hope that you will contact us or comment here on the blog in order to expand the dialog and speed up digital government initiatives.

Questions and Contact Information

For questions and other enquiries please email TBS-Cyber Security.

To join a discussion from within the GC, see GCcollab discussion.

- ↑ We expect the need for level 4 e-signatures to be rare (e.g. very high-value transactions) and the reader should consult the e-signature guidance document for additional information.

- ↑ As a reminder, security always needs to be taken into consideration, especially when dealing with parties external to the Government of Canada who may not have secure means of communication or storage. As mentioned in the e-signature guidance, confidentiality is not addressed by electronic signatures. If using an unsecure means of communication such as email, MS Word or PDF documents with the public, departments should be mindful of relevant, applicable policies. In particular, Appendix B of the Directive on Security Management states that encryption and network safeguards must be used to protect the confidentiality of sensitive data transmitted across public networks, wireless networks or any other network where the data may be at risk of unauthorized access. (B.2.3.6.3). Although sensitive information is not defined in the Directive, the Policy on Government Security defines “sensitive information” as “information or asset that if compromised would reasonably be expected to cause an injury. This includes all information that falls within the exemption or exclusion criteria under the Access to Information Act and the Privacy Act. This also includes controlled goods as well as other information and assets that have regulatory or statutory prohibitions and controls.” As such communication using public email, may not be appropriate in many given circumstances due to security risks.